How Indigenous knowledge could help tackle climate change

New US research hub wants to use the traditional ways of Native peoples to address environmental problems

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The US National Science Foundation (NSF) is funding a research hub dedicated to integrating Indigenous people's knowledge into scientific research.

The move comes amid ongoing discussions over the effects of "colonialism in science" and "a reckoning that researchers must do more to engage with native peoples when seeking their expertise in everything from flora and fauna to medicines, weather and climate", said Nature.

The newly launched Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledges and Science (CBIKS) will receive $30 million in funding over the next five years. It seeks to blend Indigenous knowledge of the environment with Western scientific methods while respecting local communities and their cultural traditions, said Sonya Atalay, an archaeologist with Anishinaabe-Ojibwe heritage at University of Massachusetts (UMass) Amherst and one of CBIKS' co-leaders.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Emphasising the importance of embracing Indigenous narratives in science, she told the journal: "As Indigenous people, we have science, but we carry that science in stories. We need to think about how to do science in a different way and work differently with Indigenous communities."

Jon Woodruff, a sedimentologist at UMass Amherst and another co-leader of CBIKS, said that the centre aims to turn standard scientific methodology "on its head". He thinks the approach has enormous potential as communities around the world seek to confront climate change.

How are Indigenous people impacted by climate change?

Indigenous peoples find themselves at the forefront of the climate crisis, experiencing its impacts more acutely and rapidly than other communities, despite contributing "least to greenhouse gas emissions", according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA).

Their deep dependence on and close relationship with the environment make them particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. This vulnerability compounds the challenges already faced by Indigenous communities, including "political and economic marginalization, loss of land and resources, human rights violations, discrimination and unemployment", added UN DESA.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Many Indigenous practices, such as native tree plantations in Nepal, community-managed forests in Bangladesh and the use of traditional technologies in the Pacific, are already playing crucial roles in combating climate change, according to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 2022. These practices store carbon, preserve local culture, meet community needs, and mitigate climate change through resource management.

The "significance and potential" of these practices are "strongly recognized" by the scientific community as key approaches to developing and implementing countries' national climate action plans under the Paris Climate Agreement, the UNFCCC added.

What does CBIKS hope to achieve?

CBIKS aims to leverage Indigenous knowledge through a global network of collaborators spanning eight hubs in four countries, said Nature. One of the initial projects, set to launch within the research hub's first year, focuses on a traditional clam farming technique practised for thousands of years by Indigenous peoples along the Pacific coast of Canada and the United States.

Marco Hatch, a marine ecologist at Western Washington University and a member of the Samish Indian Nation, has devoted nearly two decades to working with Indigenous communities to "investigate and revive this ancient technique", said the journal. This method involves using terraced gardens to extend and flatten a beach's intertidal zone, where clams thrive. Compared to conventional methods, this approach can yield two to four times more clams, according to Hatch.

Speaking to WBUR, Atalay said the centre aims to make use of Indigenous knowledge in an ethical manner, "working with Indigenous peoples as partners so that we're doing research with them rather than on them, and the research questions are coming from communities".

The centre also aims to transform the way mainstream science is carried out. She said: "Right now, science is practiced in a global, top down approach. What Indigenous knowledge does is say, 'Let's look at the local. This research has to be place based. It has to come from communities and rely on community specific knowledge to that place.'"

Atalay told Nature she recognised the importance of avoiding exploitative scenarios where scientists extract local knowledge, publish it, and subsequently profit through pharmaceutical companies.

To address this concern, the centre has established protocols for managing intellectual property, ensuring that Indigenous communities have a say in how and when outside entities use their knowledge, she told Nature.

Atalay added that scientists will also focus on ways of communicating their findings with Indigenous communities that are more accessible than publishing papers in peer-reviewed journals. This could take the form of comic books, posters and theatre, she said.

Sorcha Bradley is a writer at The Week and a regular on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. She worked at The Week magazine for a year and a half before taking up her current role with the digital team, where she mostly covers UK current affairs and politics. Before joining The Week, Sorcha worked at slow-news start-up Tortoise Media. She has also written for Sky News, The Sunday Times, the London Evening Standard and Grazia magazine, among other publications. She has a master’s in newspaper journalism from City, University of London, where she specialised in political journalism.

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

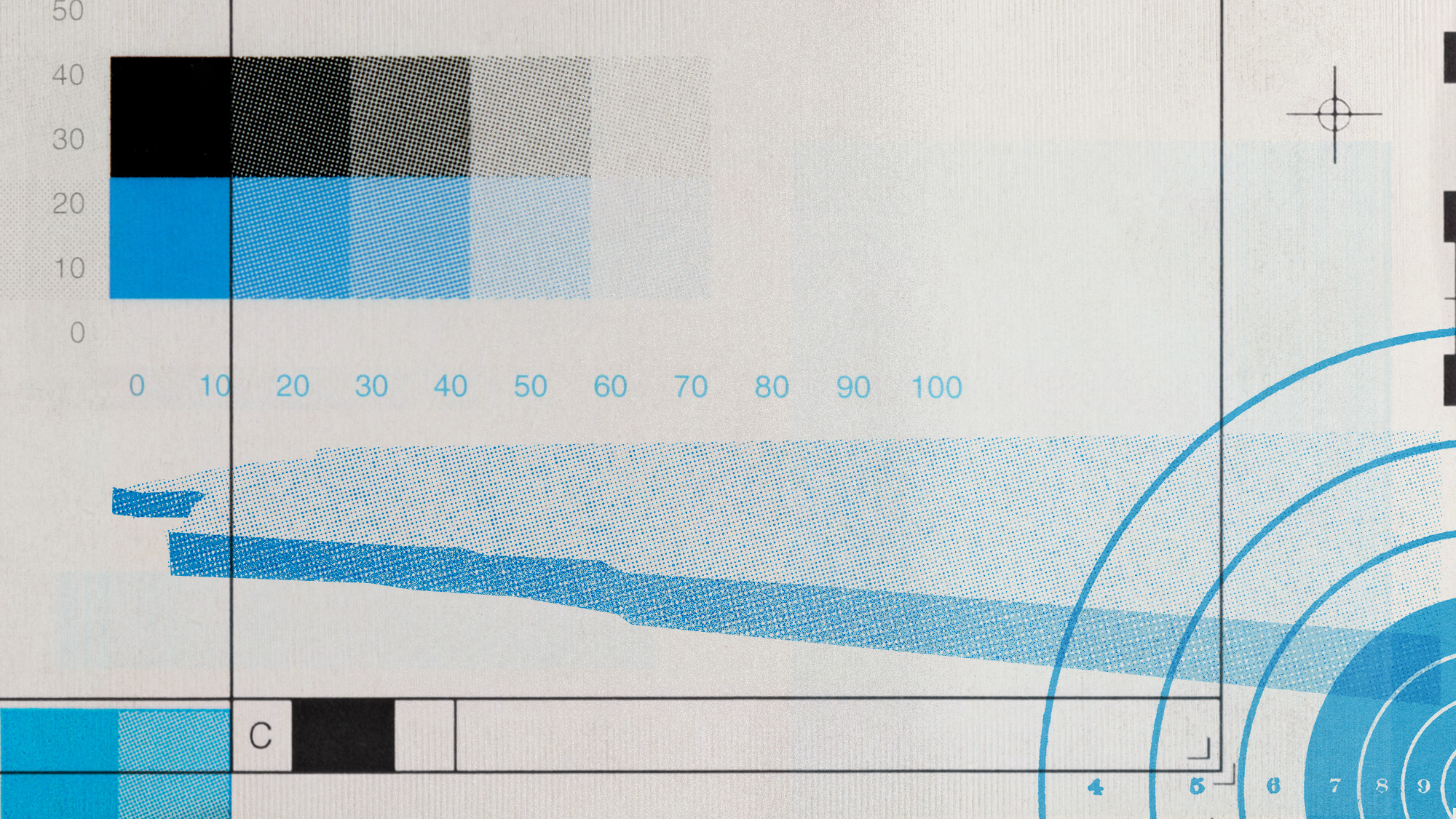

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

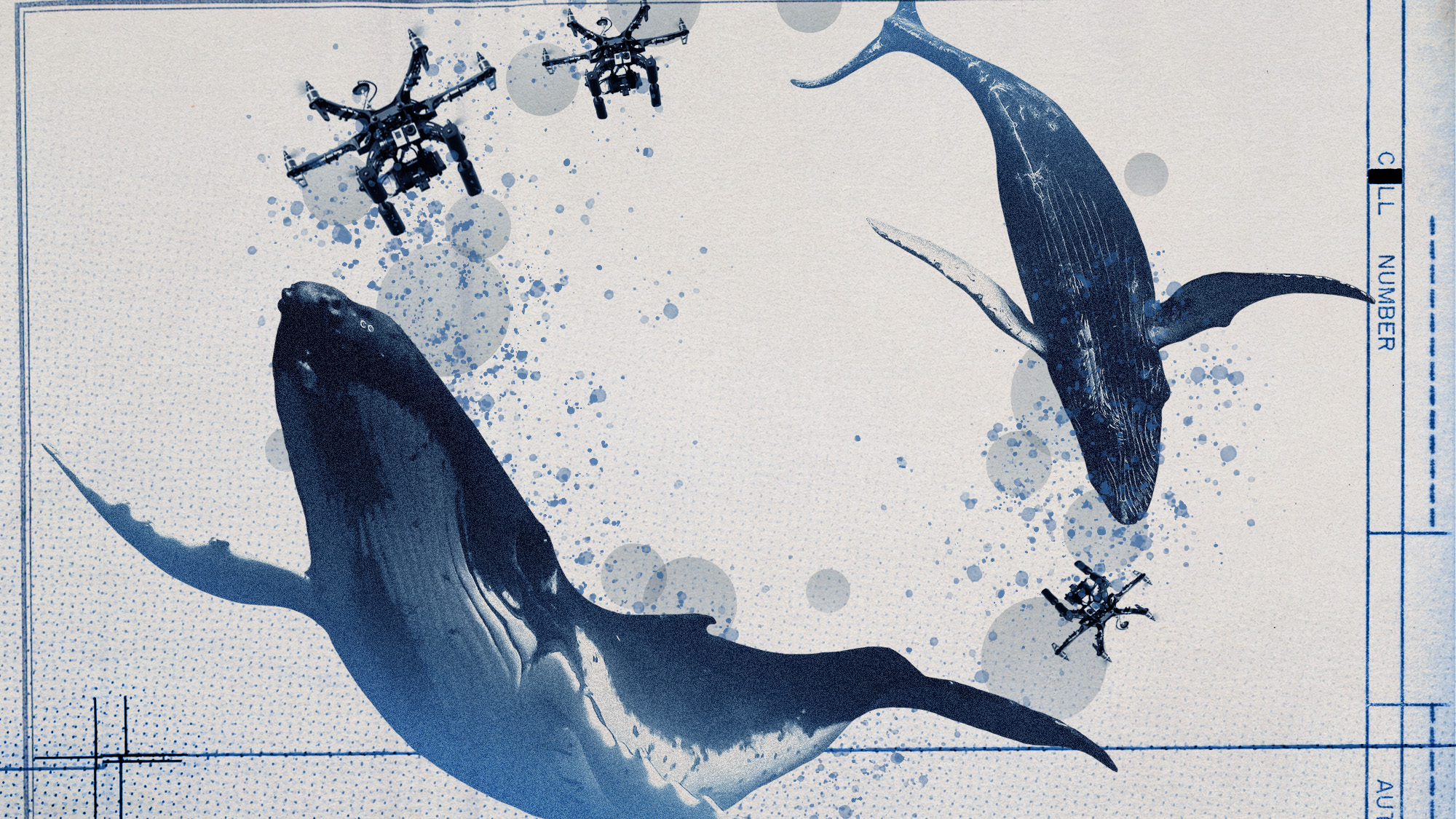

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air