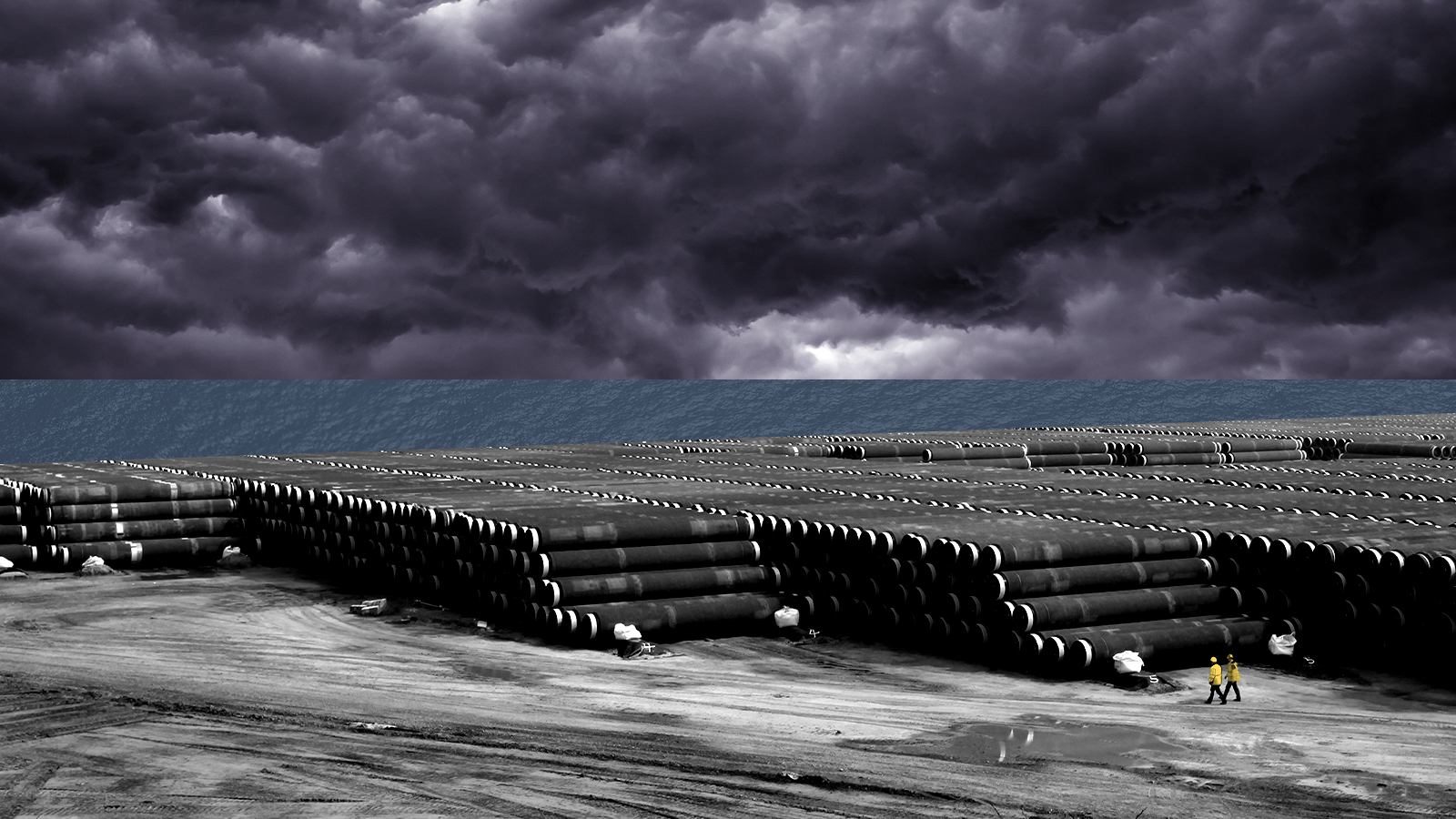

Russia's controversial 764-mile-long natural gas pipeline

What the Nord Stream 2 means for Europe — and the world

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Russia's controversial 764-mile natural gas pipeline, Nord Stream 2, is nearly complete. What will it mean for the region — and for the world?

Why is this new pipeline so controversial?

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline will transport natural gas directly from Russia to Germany via the Baltic Sea. It's under scrutiny because a fair amount of Russia-to-Europe gas currently runs through other countries, including Ukraine, which rely heavily on revenue from the transit fees. And while the original Nord Stream pipeline has been in operation since 2011 and follows the same course, the second set will double the amount of gas coming from Russia. Ukraine and other transit countries fear the Kremlin will eventually divert all of its European natural gas supplies to the Nord Stream system and put the land routes out of business. So, while Moscow and Berlin maintain that Nord Stream 2 is purely a business venture, the United States and many European countries believe it's a thinly-veiled Russian geopolitical project aimed at exerting influence over central and Western Europe while weakening its eastern neighbors.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How exactly could Ukraine be affected?

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and his foreign minister Dymitro Kuleba have argued the pipeline will not only hamper Ukraine's economy — it could cost it $2 billion in annual transit fees — but would also be a security threat since it would take away the geopolitical leverage Kyiv holds due to its middle-man status. The transit revenue also accounts for a good portion of Ukraine's defense spending at a time when the country is still mired in a military conflict with Russia and Russian-back separatists in eastern Ukraine.

But Germany is still on board?

German Chancellor Angela Merkel is usually pretty tough on Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin, but in this case, she's in a bind. German businesses believe abandoning the Nord Stream 2 project would be an expensive legal hassle and hurt Germany's reputation as a "safe investment location." Meanwhile, European gas production is falling, but demand is expected to remain stable over the next two decades. As a result, there's concern about meeting the continent's energy needs, and it doesn't hurt that the Nord Stream supply can be had at a relatively low price. Merkel and other ministers hinted the deal might be in jeopardy after Russian authorities arrested and jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny earlier this year, but that threat fizzled. Merkel is trying to draw some sort of line by demanding that Ukraine remain a transit country even after the pipeline is completed, but it's unclear whether Russia will acquiesce.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What's the U.S. stance?

Both the Trump and Biden administrations have objected to the pipeline, and it's a rare point of bipartisan agreement in the halls of Congress. There do appear to be legitimate concerns about Europe's potential over-dependence on Russian energy and Ukraine's vulnerability, but there are selfish reasons for the opposition, too: The U.S. wants to get more involved in the European gas market as a supplier. President Biden has called the pipeline a "bad deal," and Secretary of State Antony Blinken has emphasized U.S. opposition. Yet the administration waived sanctions on the company overseeing the pipeline's construction, Nord Stream 2 AG — which is owned by Russia's state-owned energy giant Gazprom — and its CEO Matthias Warnig, a former East German intelligence officer who's been described as a Putin crony.

Why waive those sanctions?

Mostly because the administration thinks opposing the effort is futile. The pipeline is 95 percent complete, so at this point the only companies that would be affected by sanctions are on the German side, and Biden doesn't want to hinder the Washington-Berlin relationship, which is bouncing back after four difficult years. And even if the administration did go ahead with penalties, there are potential workarounds: The German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, where the gas will land, has set up a foundation to try to shield private companies from sanctions.

So the pipeline is a done deal?

It sure seems like it. Putin said in June that construction of the first of two lines has been completed, and the second could be finished in a couple of months. But gas won't start flowing until a certification process is complete, so the anti-Nord Stream 2 contingent may have some ammo left. The U.S. and Germany are still engaging in private discussions on the matter, and if the U.S. can get Germany to hold out a little longer, Germany's national elections in September could be a game-changer: The German Green Party, which has enjoyed a strong showing in polls so far and could play a significant role in the next government, came out against the pipeline earlier this year for environmental and geopolitical reasons. If the Greens do grasp some power before Nord Stream 2's final certification, there's a chance the party could scuttle the project at the last minute. Ukraine, meanwhile, is prepared to take legal action against Gazprom to unlock Central Asian gas supplies it has kept a lid on for 15 years, Yuriy Vitrenko, the CEO of Ukrainian gas company Naftogaz, told The Financial Times. If successful, Kyiv likely wouldn't have to worry as much about Nord Stream 2 rendering its own pipelines useless. "Central Asian gas alone can fill the whole Ukrainian gas transit system," Vitrenko said.

Tim is a staff writer at The Week and has contributed to Bedford and Bowery and The New York Transatlantic. He is a graduate of Occidental College and NYU's journalism school. Tim enjoys writing about baseball, Europe, and extinct megafauna. He lives in New York City.