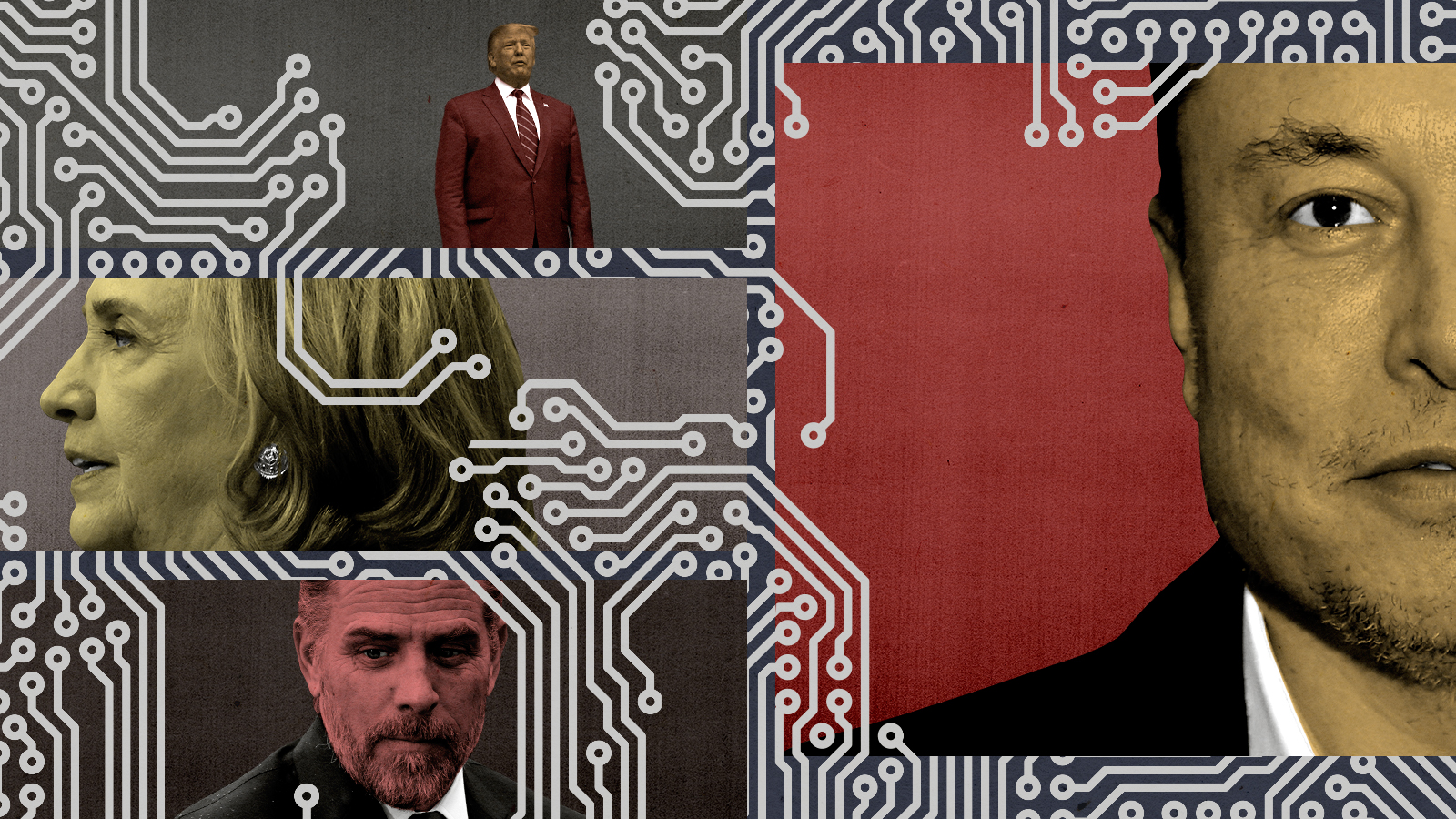

Musk, Twitter, and the balance of digital power

Why the billionaire's freewheeling approach to moderation may be the only option we have

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The timing couldn't have been more perfect.

Exactly 90 minutes before Monday's announcement that Twitter's board had approved entrepreneur Elon Musk's bid to buy the platform, Hillary Clinton enthusiastically tweeted, "They got it done!" Accompanying her celebratory pronouncement was a link to a New York Times story about the passage of landmark legislation in the European Union that will "address social media's societal harms by requiring companies to more aggressively police their platforms for illicit content or risk billions of dollars in fines."

Musk himself tweeted a comment on his acquisition soon afer the former Democratic presidential nominee's cheer for regulation. "Free speech is the bedrock of a functioning democracy," he wrote. And there, sitting side by side, were two contrasting visions of how to respond to the challenges of a digitally networked world.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the one embraced by Clinton and the EU, public institutions impose control from above, establishing uniform standards of acceptable speech and behavior online in an effort to exclude the political and epistemological extremes and thereby advance the public good. The one advocated by Musk is rhetorically more libertarian, animated by faith in the ability of a largely open marketplace of ideas to reward the worthwhile and punish the false and the frivolous.

Which will it be? Top-down imposition of online control? Or hope for at least a modicum of order emerging spontaneously out of chaos?

I understand why so many long for the former. The government's role should be, in part, to enact policies that prevent bad things from happening in civil society — which in the present context includes the spread of lies, conspiracies, disinformation, abuse, and political antiliberalism on digital media platforms. Yet I fear those on this side of the argument fail to grasp the magnitude of the challenge.

In a democracy, government actions need to be broadly viewed as legitimate. But perception of legitimacy depends on the existence of a social and political consensus about what the problem is and how best to address it. There is no such consensus today.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How was it lost? It's a complicated story, with different variations unfolding across the democratic world. But the very tech platforms Clinton and the EU want to regulate have played a big part in the loss. Social media networks at once amplify the voices of those previously excluded from political participation and allow these newly empowered individuals and groups to form virtual factions across vast physical distances.

Some of these individuals and groups are on the political extremes. Some are prone to embracing and spreading conspiracy theories about everything from election subversion to the supposed dangers of vaccines. Many distrust the political and cultural establishment that formed and upheld the reigning consensus of past decades; they are therefore open and easily attracted to politicians who deploy populist rhetoric against that establishment.

This distrust has many sources. Some of it flows from a kind of temperamental paranoia about powerful institutions as such. But it also comes from observing members of the establishment on these very same social media networks. Far from dispassionate public servants calmly assessing problems and devising measured policy responses, many appear downright unhinged and paranoid, indulging conspiracy theories and exaggerations of their own — with plenty of them contemptuously directed at the newly empowered digital masses.

And that's where problems arise for efforts to regulate tech platforms. Those who favor doing so are not wrong to sense a need: In addition to citizens honestly engaging in argument and debate online, social media networks are teeming with bad actors, some of them controlled by hostile foreign governments and domestic troublemakers, who use bots, sock puppets, and other techniques to pollute the information space. Meanwhile, the algorithms tech companies use to increase "engagement" and advertising revenue on their platforms can end up creating echo chambers where extremism festers.

All of it cries out for some kind of policy response. The trouble is determining what that response should be, and, more importantly, who will oversee it.

So far, the best anyone has come up with is content moderation. The churning chaotic flows of information need to be monitored by an umpire of some sort, with certain people, ideas, and acts ruled out of bounds. That sounds reasonable. Even Reddit, a forum network that permits a very wide range of opinion, has outer-bound rules that it polices. It makes sense that other platforms would do something similar.

To an extent they always have. (It's never been acceptable to post child porn on Twitter or Facebook, for example.) The idea is that they should be doing more — much more.

It's an obviously compelling idea. Spreading the message that mRNA vaccines produce widespread, deadly side effects can persuade people not to get vaccinated, which can lead to greater number of deaths from COVID-19. Promoting an unsubstantiated story about corruption involving the son of a presidential candidate just weeks before an election might influence the results. Circulating unsubstantiated conspiracy theories about voter fraud can spark an insurrection in the nation's capital, threatening the peaceful transfer of power. Governments should ensure that tech companies use content moderation to prevent all of this and whatever new lies pop up next.

There's just one problem: The process of line-drawing, of deciding which opinions are acceptable and which are not, is not a disinterested act. It might appear so during times of broad social and political consensus, when the vast majority of people agree about what should be considered beyond the pale. But this is not such a time. In our time, drawing those lines inevitably looks like a political act — in part because it is.

The two sides of our most intractable political disagreements are not always acting in bad faith here. The mRNA vaccines are safe and effective, but public-health authorities made countless mistakes during the COVID-19 pandemic that understandably undermined the trustworthiness of their confident pronouncements. The New York Post story about the contents of Hunter Biden's laptop was suspicious, but that doesn't mean it made sense to block it from social media — especially in light of the fact that its main points have subsequently been confirmed by other news outlets.

As for acting to curtail the spread of nonsense about voter fraud encouraged by a sitting president in order to justify overturning the results of a free and fair election and keeping himself in power, that's the easiest case of all in favor of content moderation leading to a social media ban — at least so long as the bad actor himself remained in office. The case for continuing to exclude him after he left office was weaker, and it will likely disappear entirely when and if he launches another campaign for the presidency.

That won't stop some from saying the ban should be continued indefinitely because Donald Trump remains a threat to American democracy. I agree with that judgment of Trump — but I'm not sure tech companies should act on it, precisely because it's possible he could win the 2024 election outright. Trump enjoys strong support from tens of millions of Americans. Seeking to muzzle him will inevitably be viewed by those supporters as a power grab — a partisan act of manipulating the rules to benefit his opponents. It's inevitable that Trump and his party would use such a move as fuel for their anti-establishment fire.

That's the risk of the regulatory option in a nutshell: In the absence of a broad-based consensus about what counts as extreme, the very act of attempting to exclude the extremes can empower them.

It might be better to try defeating the extremes in the open marketplace of ideas and the democratic political arena rather than by attempting to regulate them out of existence. That's the path opened up by Elon Musk's purchase of Twitter — and it's an option I find modestly encouraging. Perhaps that's because I still have faith in the power of good ideas to prevail over bad.

But even if that faith is misplaced, it wouldn't necessarily mean the regulatory approach will work any better. It might simply mean, instead, that none of us has a good idea about how to put the populist genie back in the bottle.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

DOGE shared Social Security data, DOJ says

DOGE shared Social Security data, DOJ saysSpeed Read The Justice Department issued what it called ‘corrections’ on the matter

-

‘The security implications are harder still to dismiss’

‘The security implications are harder still to dismiss’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025The Explainer From Trump and Musk to the UK and the EU, Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a round-up of the year’s relationship drama

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

X’s location update exposes international troll industry

X’s location update exposes international troll industryIn the Spotlight Social media platform’s new transparency feature reveals ‘scope and geographical breadth’ of accounts spreading misinformation

-

‘We’re all working for the algorithm now’

‘We’re all working for the algorithm now’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party