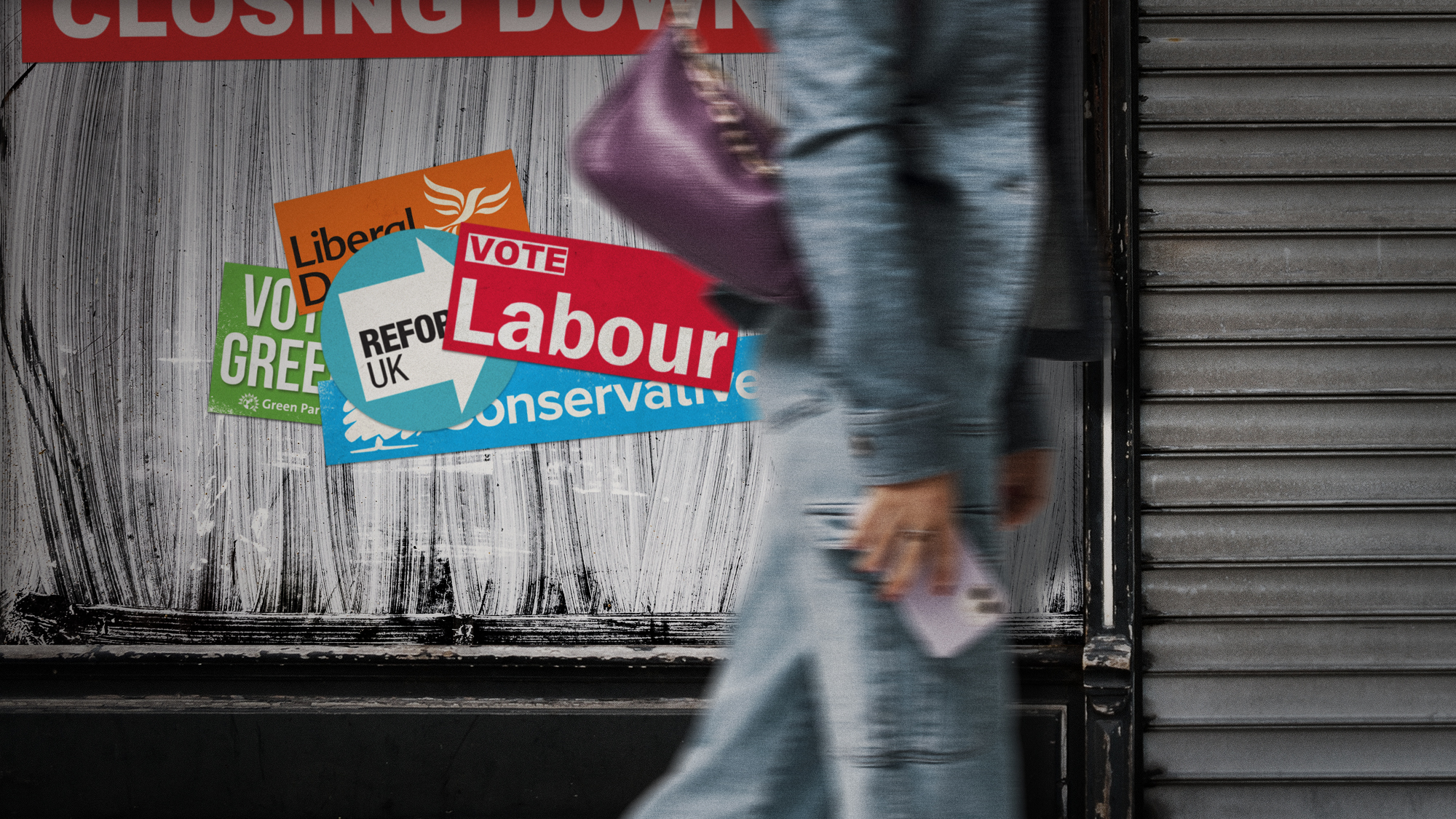

Britain's return to two-party politics

Whatever happens on Thursday, one thing is certain - this election will remembered for the polarisation of UK politics

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

While polls for tomorrow's general election vary wildly, they all suggest the UK's two main political parties are on course to win 80 per cent of votes between them, more than in any other election in 40 years.

"The uptick reverses a trend which has lasted for decades," says Buzzfeed. The combined vote share of the country's two biggest parties fell from more than 90 per cent in the 1950s to around 65 per cent in recent elections.

Why has this happened?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Mostly this is because the smaller parties are becoming less popular," Steve Fisher, associate professor of political sociology at Oxford University, told Buzzfeed.

Ukip won 12.5 per cent of the vote at the 2015 general election, but its support has since collapsed and it is struggling to articulate a purpose after the EU referendum, particularly with Theresa May taking a hard line on Brexit.

In addition, the anticipated Lib Dem surge has failed to materialise. "Part of this has been attributed to the acceptance by many Remain voters that Brexit is going to happen," says the Financial Times, while polling also suggests the party is still suffering the effects of entering into a coalition with the Tories in 2010.

The Greens "look largely irrelevant since they no longer outflank Labour on the Left while their key policies, such as rail nationalisation, have been plundered by their rival", says CapX. A lack of charismatic leadership in the Lib Dems and Ukip and a first-past-the post electoral system that fails to translate popular support into seats have also contributed to the dwindling support for smaller parties, it adds.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But, says Molly Kiniry in the Daily Telegraph, this is only half the story. The collapse of Ukip has been good for May, she says, "but the rise of the Tories has been matched by the rise of a more united Left – cleaving the country in two along ideological lines".

The Prime Minister has positioned herself in direct opposition to Labour's Jeremy Corbyn, "encouraging an us-versus-them mentality" reminiscent of a US presidential campaign while "trying to squeeze different constituency groups into two parties, with the result that the moderate-minded participants – like Labour's Blairites – lose out".

Earlier elections were fought for control of the centre ground, but the increasingly polarised positions of Labour and the Conservatives have, says Buzzfeed, "allowed both parties to pick up the votes they'd lost on their own fringes".

Labour is once again "the home of angry protest votes once lost to the Greens while the Tories soak back up millions of votes taken from them by Ukip", says CapX.

The party has also benefited from the weak polling numbers of the left-of-centre fringe parties "as some voters are deciding the only way to minimise the size of May's majority is a vote for Labour", says Buzzfeed.

Is the shift back permanent?

Labour and the Conservatives should not assume that this year's resurgence marks the beginning of a new era of two-party dominance, Professor Thom Brooks of the University of Durham told the Financial Times.

"If a strong personality appears, like Emmanuel Macron, who is rooted in a big political party, standing above it, they could attract crowds," he said. "Society is very sceptical and cynical about mainstream parties, people are looking for some change. There is room on the political stage for a Macron-style victory."

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?Today's Big Question Pathway to a coup ‘still unclear’ even as potential challengers begin manoeuvring into position

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025The Explainer From Trump and Musk to the UK and the EU, Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a round-up of the year’s relationship drama

-

‘The menu’s other highlights smack of the surreal’

‘The menu’s other highlights smack of the surreal’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

The launch of Your Party: how it could work

The launch of Your Party: how it could workThe Explainer Despite landmark decisions made over the party’s makeup at their first conference, core frustrations are ‘likely to only intensify in the near-future’

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support