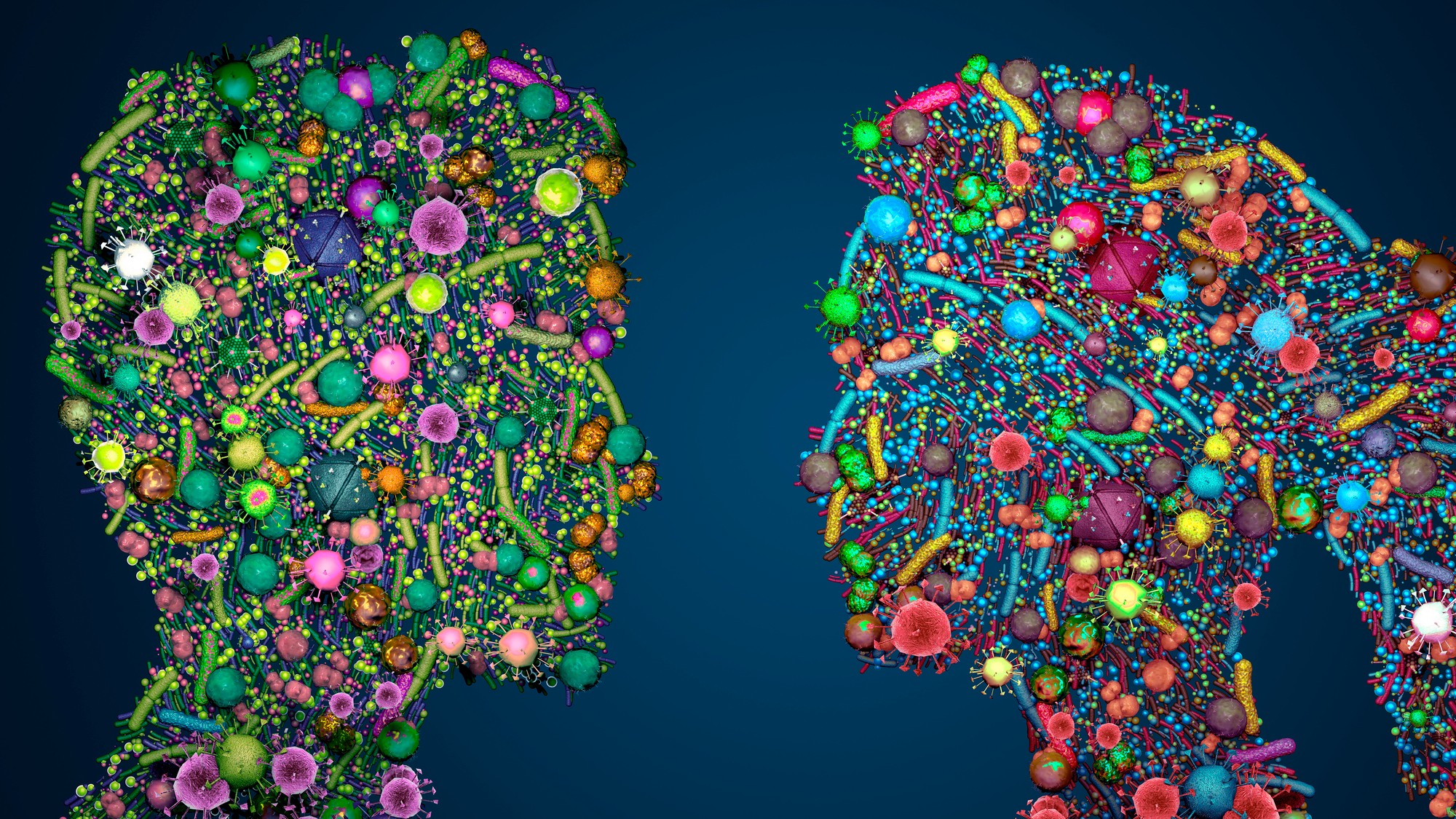

Our microbiome is social like us

Microbes can be friendly too

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Each person and animal has a unique microbiome, the individual microbial ecosystem of the body. It can affect our health and immunity. Scientists are now exploring the idea that the microbiome may be social, and interacting with multiple microbiomes can potentially be beneficial. On the flip side, disease and antibiotic resistance can transfer between organisms.

How is the microbiome social?

Just like how being near a sick person can potentially lead to catching their disease, scientists have found that good microbes can be passed along as well. A perspective piece published in the journal Cell placed importance on the social microbiome or the "microbial metacommunity associated with a social network of humans or other animals," and how it could "play a role in individuals' susceptibility to, and resilience against, both communicable and non-communicable diseases," said The Harvard Gazette.

The human microbiome has already been known to play a significant role in health and can affect the immune system, digestive system and even mental health. It is also highly individual and can vary greatly between different people. Scientists have known that factors including diet, lifestyle and environment can affect the microbiome, but social interactions can also play a part. "The host's social environment and interactions are emerging as important factors influencing microbiome composition," said a 2022 perspective piece published in Nature Ecology and Evolution. "Variation in the microbiome within and between species likely depends on variation in the structure, strength and stability of social connections."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How can the social microbiome affect disease transmission?

The social microbiome may be playing a larger role in spreading disease than previously thought. "If microbes contributing to disease can be transmitted between individuals, some non-communicable conditions may in fact have a communicable component," said Rachel Carmody, co-author of both pieces, to The Harvard Gazette. This means that even diseases that are not considered contagious can potentially still have an element of contagiousness. "While that may be a potentially unsettling thought, socially transmitted microbes may help protect against these conditions, too."

Good microbes may also be contagious. "Social interactions can provide conduits for pathogen transmission, but beneficial microbes are also known to be transmitted through these interactions," Andrew Moeller, co-author of both pieces, said to The Harvard Gazette. "It may be that, in some contexts, the benefits provided by socially transmitted mutualists outweigh the costs incurred by socially transmitted pathogens." For example, studies done on mice have found that sharing the same space caused microbes to transfer between the animals, which helped improve the response to cancer therapy.

One of the negatives is that antibiotic-resistant microbes can also be transferred. Antibiotics are designed to kill microbes and bacteria. However, those that survive can become immune to the medication and create a strain that can no longer be killed with this treatment. "We can't think of microbes in a binary way — as good or bad bugs because they adapt themselves to the situations they find themselves in," Fergus Shanahan, founder and former director of APC Microbiome Ireland, said to the Irish Times. As a result, "individuals who share a household might acquire antibiotic-resistant microbes from each other if some members are under prolonged antibiotic treatment," The Harvard Gazette said.

"When we think of factors that affect the microbiome, diet and antibiotics come to mind most readily," said Amar Sarkar, lead author of both perspective pieces, to the Gazette. "But the fact that our social interactions also affect the microbiome is less well appreciated."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.