A history of the Gentleman's Clubs of London

The Garrick's decision to admit women has put London's 'Clubland' in the spotlight

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

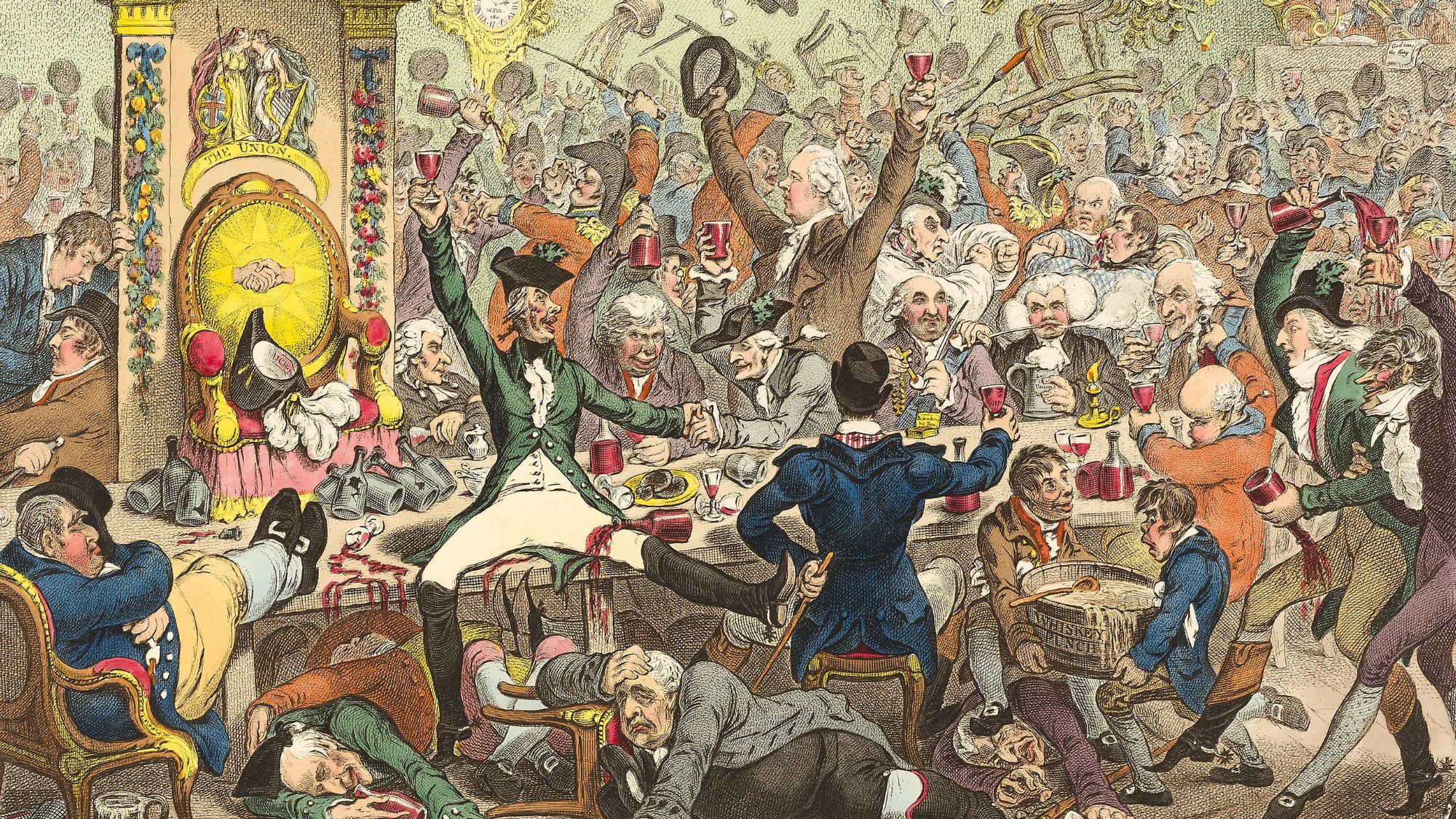

London's oldest gentlemen's club, White's, began life in Mayfair in 1693 as Mrs White's Chocolate House, founded by an Italian migrant, Francesco Bianco. It was a place where men could meet up, eat, drink and socialise – with a gambling room in the back. It became fashionable, and notorious for bad behaviour and massive gambling losses – Jonathan Swift called it the "bane of half the English nobility". In the late 18th century a series of similar institutions sprang up in St James's in the West End of London. Boodle's started up in a tavern in 1762, and was named after its head waiter. White's was for Tories, Brooks's was for Whigs, Boodle's for the country set. These clubs became known in the Georgian period for their atmosphere of aristocratic excess, says Seth Alexander Thévoz in his history Behind Closed Doors, and for "days-long around-the-clock gambling fuelled by port and laudanum".

How were clubs different after the Georgian era?

The Victorian era was the heyday of the club. They became more respectable, and took the form that they still have today: a typical one would be located in a grand Palladian mansion on St James's Street, on Pall Mall, or nearby – an area known as "Clubland" – and would have a formal dining room with a shared table, a bar, a library, a billiards room, private rooms for gambling and bedrooms for members who needed them. Clubs multiplied: there were more than 400 in London, reflecting common interests and professions. The Reform Club, founded in 1836, was for Liberals; the Carlton Club for Conservatives; The Athenaeum for men in the arts and sciences; The Garrick Club for actors and writers; The Army & Navy for the Forces; The East India Club for those who had served in India. Later, women's clubs such as The Pioneer Club and the Alexandra were also set up, a little further north.

Why were they so popular?

They were often described as a home from home. Various theories have been advanced for their appeal: that aristocrats needed somewhere to relax, because they felt on show in their own grand homes; that MPs, who were increasingly drawn from the provincial middle classes, needed somewhere to stay, meet and work in London; that men educated in boarding schools wished to recreate similar all-male environments; that London's growing professional classes enjoyed spending time in grand surroundings and wanted to make influential contacts. At a certain point, club membership became so ubiquitous among "gentlemen" that for many it was unthinkable not to join one. At any rate, for more than 100 years, clubs became a central feature of the British establishment. Edward Ellice, a 19th century Whig MP, said that the UK had a system of "club government".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What about the snob value?

The exclusivity was undoubtedly important. Benjamin Disraeli remarked that there were only two things that an Englishman couldn't command – being made a Knight of the Garter, and a member of White's. Members had to be elected: proposed by one existing member, seconded by at least one other, then voted on by the rest, anonymously, often using white or black marbles: the number of black balls that would lead to a rejection, or blackballing, varied from club to club. Members were expected to observe strict dress codes and other rules, and to exhibit the more general and ill-defined quality of being "clubbable".

How have they changed since?

Clubs retained their importance in the early years of the 20th century, though few new institutions were formed – the exception being Buck's, founded by Captain Herbert Buckmaster after the First World War, because he wanted a rather less stuffy atmosphere and, shockingly to some, an American cocktail bar. Buck's would inspire P.G. Wodehouse's Drones Club, and give the world the Buck's fizz, invented there in 1921. After the Second World War, London's clubs greatly declined in number; they began to seem hidebound and at odds with an increasingly meritocratic culture – often associated with "club bores" and old men sleeping in armchairs.

So what's left of them now?

Today, there are about 40 gentlemen's clubs in the capital, according to the Association of London Clubs. To some extent they have been supplanted by a new breed of private members' clubs, such as Soho House, The Groucho Club and 5 Hertford Street, which are more glitzy, and run as commercial operations, not member-owned organisations. Such clubs also, of course, admit women. Many of the remaining gentlemen's clubs have changed, to a certain extent. The first of the old breed to admit women on an equal basis was The Reform Club, in 1981. The Athenaeum followed in 2002. Most now do so, although membership remains overwhelmingly male. Pratt's has admitted just two or three women since changing the rules last year.

Which clubs don't admit women?

Only a handful are still male-only: The Travellers Club, the Savile Club, The Beefsteak Club, Boodle's, Buck's, Brooks's, The East India Club and White's. The right to remain single- sex institutions is protected by law, in the Equality Act 2010, but pressure is mounting: the East India and the Savile are reportedly wavering. Even the Beefsteak Club, where waiters are all addressed as "Charles" to save members the bother of remembering their names, is said to be considering it. Several are holding out, though. The Travellers rejected the idea of female membership in 2014, with one member noting that a single-sex club allowed them to enjoy "male banter, without having to bother with the etiquette that one inevitably must adhere to in female company (whether it be offering her drinks, waiting for her to eat, or standing when she arrives or leaves)".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

Best places to find snowdrops in the UK

Best places to find snowdrops in the UKThe Week Recommends The snowdrop season is upon us, with ‘blankets’ of the beautiful bloom signalling that spring is on its way

-

The 8 best superhero movies of all time

The 8 best superhero movies of all timethe week recommends A genre that now dominates studio filmmaking once struggled to get anyone to take it seriously

-

American empire: a history of US imperial expansion

American empire: a history of US imperial expansionDonald Trump’s 21st century take on the Monroe Doctrine harks back to an earlier era of US interference in Latin America

-

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa Parks

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa ParksIn The Spotlight Inspired by the example of 19th century abolitionists, 15-year-old Colvin refused to give up her seat on an Alabama bus

-

Decking the halls

Decking the hallsFeature Americans’ love of holiday decorations has turned Christmas from a humble affair to a sparkly spectacle.

-

Hitler: what can we learn from his DNA?

Hitler: what can we learn from his DNA?Talking Point Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator is the latest documentary to posthumously diagnose the dictator

-

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025The Explainer From prehistoric sunscreen to a brain that turned to glass, we've learned some surprising new facts about human history

-

How did Kashmir end up largely under Indian control?

How did Kashmir end up largely under Indian control?The Explainer The bloody and intractable issue of Kashmir has flared up once again

-

The fall of Saigon

The fall of SaigonThe Explainer Fifty years ago the US made its final, humiliating exit from Vietnam

-

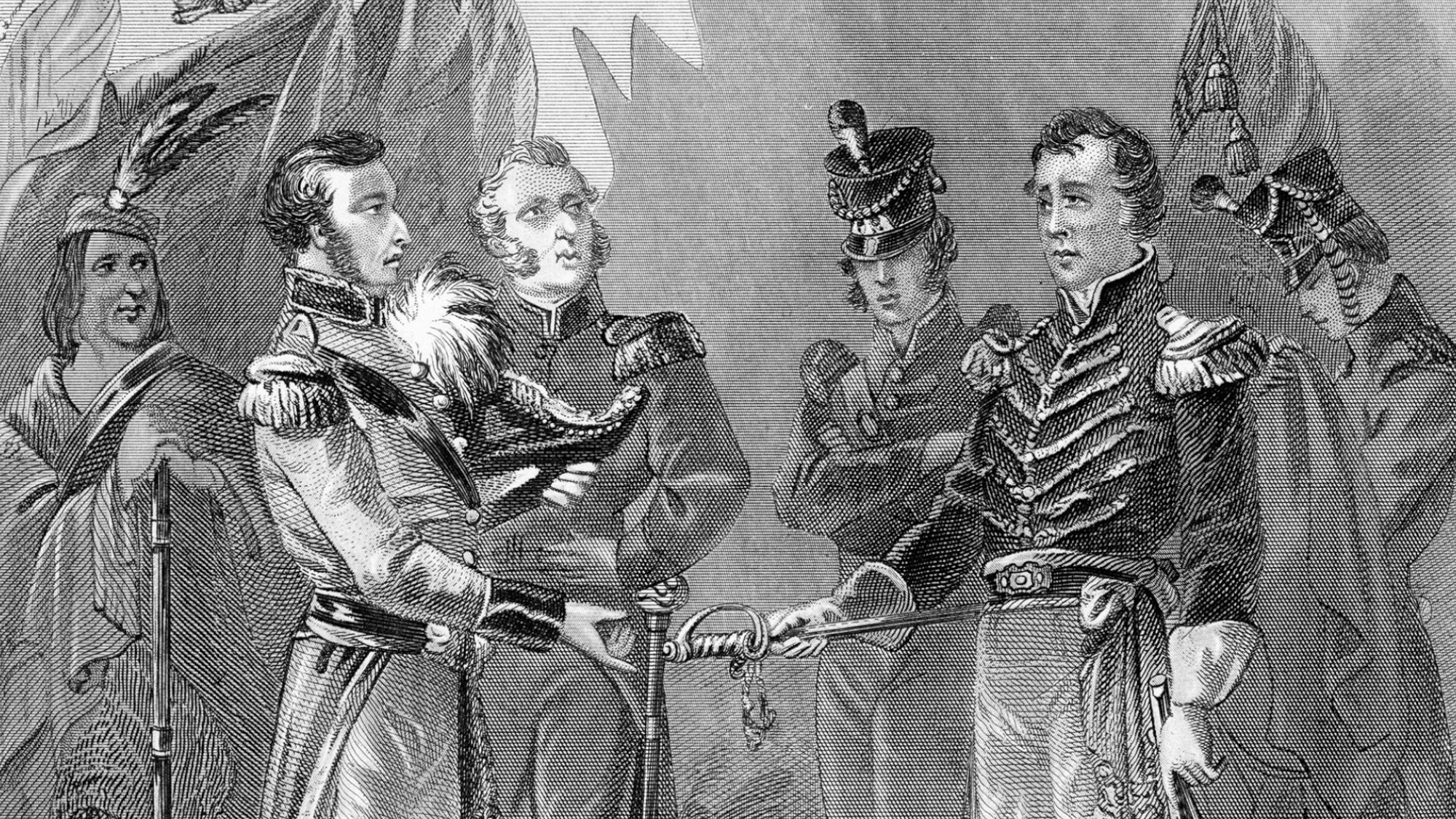

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.