The flaw in New Year's resolutions

Every January, nearly half of Americans pledge to make big changes. Why will most of us fail?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Every January, nearly half of Americans pledge to make big changes. Why will most of us fail? Here's everything you need to know:

How did the tradition start?

New Year's resolutions go back at least 4,000 years, to the Babylonians. The ancient Mesopotamian culture is believed to be the first to have celebrated the new year, but in March, not January, to coincide with the start of the growing season. As part of Akitu, their 12-day religious festival, they pledged to the gods to repay debts and return borrowed items. During the Roman Empire, Julius Caesar established Jan. 1 as the start of the year around 46 B.C., and Romans used the month of January to reflect on the previous year and make promises of good behavior. The month itself was named for Janus, the god of beginnings and endings. In the Middle Ages, medieval knights renewed their pledges of chivalry at the end of the year with "The Vow of the Peacock," placing their hands on the noble bird. The first recorded use of the term "New Year resolution" comes from a Boston newspaper in 1813. Around that same time, Walker's Hibernian Magazine or Compendium of Entertaining Knowledge in Ireland satirized the tradition, suggesting that doctors should resolve to "be very moderate in their fees" and politicians to "have no other object in view than the good of their country."

Why do so many people set New Year's resolutions?

Surveys show that there is something irresistible and emotionally resonant about the possibility of fresh starts. There's a reason why so many cultures share a version of the holiday, from the Western New Year on Jan. 1 to the Jewish and Chinese, or lunar, New Year's celebrations in autumn and midwinter. The beginning of a new year is a milestone that can make people feel unusually inspired and optimistic, and dramatic personal transformations are one of our favorite things to imagine. "For most people, resolutions represent the fantasy of perfection — perfect body, perfect life, perfect feelings — without any of the reality," said psychologist Sasha Heinz. Almost half of Americans make New Year's resolutions every Jan. 1, but studies show that just 8 percent stick with them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What are common resolutions?

A YouGov poll found that the resolution most frequently made was to exercise more. That was followed closely by losing weight, saving money, and adopting a healthier diet. Those trends have held true for years: A 2017 study found that about 55 percent of resolutions were health-related, with nearly one-third revolving around exercise and about 10 percent connected to healthier eating. About 34 percent were about work or personal finances and about 5 percent were social, including a vow to spend more time with family and friends.

Why do people fail?

Habits are, by definition, deeply ingrained, so even the best of intentions aren't enough to turn an idealized future into reality. By mid-February, some 80 percent of people will give up on their resolutions. Research has found that rewarding habits like overeating or overspending are very hard to quit, and that we need to feel rewarded by — and actually learn to enjoy — our new habits if they're going to last. Many people also dream too big, as if they will wake up a wholly new person on Jan. 1. Gym memberships spike in early January, as does physical activity measured by workout apps like Strava, but within weeks, there's a steep drop-off. Analysts call this date, often in early February, "Fall Off the Wagon Day" or "Quitter's Day." University of Chicago behavioral scientist Ayelet Fishbach refers to the challenge of sustaining change after the initial motivation has worn off but before the end goal is in sight as "the middle problem." She says that humans need short-term successes to feel sufficiently rewarded to keep going and achieve long-term habit shifts.

How would that work?

To start, researchers advise, break up your goals into smaller, concrete, incremental steps, instead of jumping into major lifestyle changes that create great discomfort. Success with little challenges can be rewarding and build confidence — and new habits. Being specific is also critical: If you're aiming to be a better family member, you can, for example, set aside 30 minutes a week for a visit or phone call with a relative. If you do no exercise at all and would like to become more active, start with a 15-minute daily walk rather than joining a gym or buying a $2,000 exercise machine that will soon gather dust. To put money into savings, Fishbach suggests setting a monthly goal, rather than an annual one. "Our goals may set the tone and motivate us to create habits," said psychologist Charissa Chamorro of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. "But it's actually engaging in daily, context-specific behaviors that creates a habit."

Rethinking the tradition

Since almost everyone who sets a resolution fails to keep it, behavioral psychologists say, it's time to re-examine this tradition and find ways to set goals that are likely to be achieved. Big, sweeping lifestyle changes such as "I will avoid unhealthy food and exercise five times a week" are hard to sustain, but tiny ones such as "no more sweets" can also fail if they feel detached from any larger aim. Some psychologists suggest that three years of living with the uncertainty and stress of the pandemic has drained many people's emotional resources, making it more difficult to take on major changes. Partly for that reason, the tradition of New Year's resolutions appears to be waning among Millennials and Gen Zers, The New York Times has reported. Alex Boughen, 29, told the Times he got tired of always failing to keep his resolutions and of the accompanying negative feelings. He realized he could be more forgiving and gradually work up to his big-picture goals — he'd go on an after-dinner walk if he missed a morning run, rather than beating himself up about not sticking to a strict plan. "If I don't hit a goal one day, I just try again the next day," he said. "It's a much better strategy than waiting until the new year to try again."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Wellness retreats to reset your gut health

Wellness retreats to reset your gut healthThe Week Recommends These swanky spots claim to help reset your gut microbiome through specially tailored nutrition plans and treatments

-

7 hot cocktails to warm you across all of winter

7 hot cocktails to warm you across all of winterthe week recommends Toddies, yes. But also booze-free atole and spiked hot chocolate.

-

Appetites now: 2025 in food trends

Appetites now: 2025 in food trendsFeature From dining alone to matcha mania to milk’s comeback

-

11 extra-special holiday gifts for everyone on your list

11 extra-special holiday gifts for everyone on your listThe Week Recommends Jingle their bells with the right present

-

10 great advent calendars for everyone (including the dog)

10 great advent calendars for everyone (including the dog)The Week Recommends Countdown with cocktails, jams and Legos

-

Dry skin, begone! 8 products to keep your skin supple while traveling.

Dry skin, begone! 8 products to keep your skin supple while traveling.The Week Recommends Say goodbye to dry and hello to hydration

-

Sowaka: a fusion of old and new in Kyoto

Sowaka: a fusion of old and new in KyotoThe Week Recommends Japanese tradition and modern hospitality mesh perfectly at this restored ryokan

-

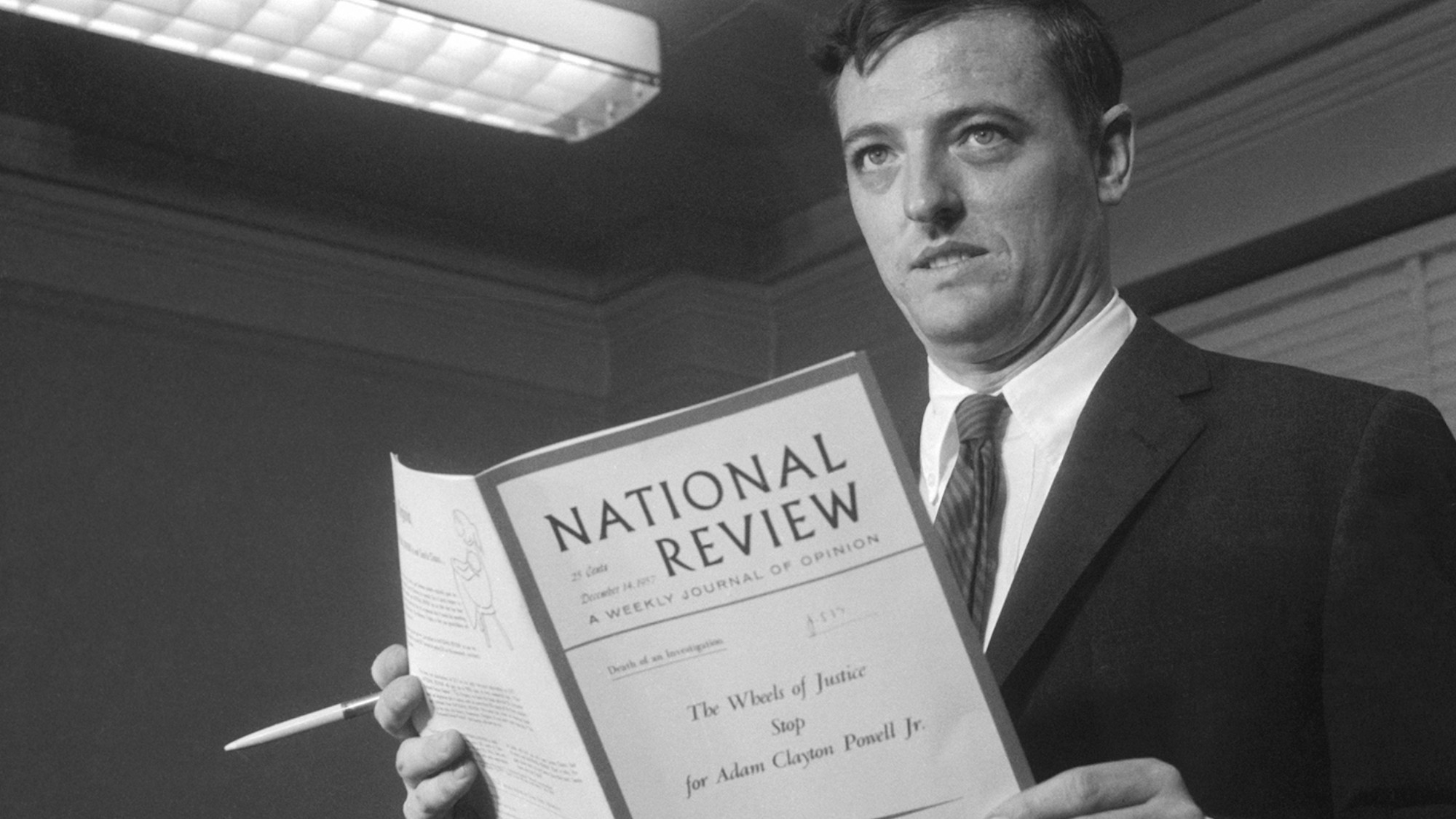

Book reviews: 'Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America' and 'How to Be Well: Navigating Our Self-Care Epidemic, One Dubious Cure at a Time'

Book reviews: 'Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America' and 'How to Be Well: Navigating Our Self-Care Epidemic, One Dubious Cure at a Time'Feature How William F. Buckley Jr brought charm to conservatism and a deep dive into the wellness craze