Democrats are learning a vintage lesson about inflation

The party already had plenty of reason to worry. Then came the inflation report.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Rising prices on cars, gasoline, food, and lots else sent U.S. inflation to a three-decade high in October, according to a Labor Department report released on Wednesday. And that 6.2 percent increase reminds me of something Republicans in Washington were confidently saying in private over the summer.

Were they worried that a powerful economic recovery might give Democrats enough momentum to win the 2022 midterms and keep control of Congress? Not really, they claimed. President Biden's tsunami of spending would surely cause a price surge and turn voters against Bidenomics like they did Carternomics. Aren't those the ironclad political and economic lessons of the 1970s inflation spiral that gave us President Ronald Reagan, hallowed be his name?

Had Democratic politicians been witness to those conversations, they likely would have scoffed at the GOP electoral theory as mere whistling past the political graveyard. Sure, a burst of consumer demand from the reopening economy and a few one-off supply glitches, as in the automotive industry, were boosting prices. So what? The economic consensus was that the current inflation spike would be merely "transitory" and nothing like the persistent 1970s "Great Inflation." Then, years of higher prices created a self-fulfilling inflationary expectation that only ended with the 1981-1982 recession, along with a clear and sustained Federal Reserve commitment to keep inflation low.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Such thinking even had the imprimatur of the lodestar of center-left econ punditry: "Don't worry about inflation: Why fears of the return of 1970s-style inflation are overblown," directed a Vox headline from July. And Larry Summers, a Democratic-leaning economist who expressed inflation concerns about the Biden agenda, was roundly mocked by lefty pundits.

Democrats are now learning the hard way, however, that economic analysis should never be confused with political analysis. Recent polls are suggesting inflation doesn't need to be "great" or long-lasting to sour voters on the economy, even a fast-growing economy in which unemployment is falling.

A recent New York Fed survey found households' short-term inflation expectations reached a record high of 5.7 percent in October, up 0.4 percentage points since September. Meanwhile, just 35 percent of Americans now call the national economy "good" while 65 percent call it poor, according to a poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. That economic approval rating is down sharply from 45 percent in September. Finally, a Reuters/Ipsos poll connects inflation expectation and economic approval trends: Two-thirds of the country, including majorities of Democrats, Republicans, and independents, say "inflation is a very big concern for me."

The psychology of rising prices is a strange one. Even if wages are rising as fast, or even faster, an inflation upturn can unnerve people. Not only has it been a while since many of us have experienced a period of sharply rising prices, but an inflation shock also makes the economy seem fundamentally unstable. That's another 1970s lesson: The Great Inflation was accompanied by four recessions between 1969 and 1982.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Sure, you can try to reassure voters that inflation is temporary by giving them all sorts of fancy economic reasoning. But that doesn't change what they are paying at the gas pump, for instance, where prices are at a seven-year high. Even worse, inflation is starting to look a bit less transitory than it did a few months ago. Analysis by Capital Economics points out that although some prices (like gas) look like they may be ready to reverse, others (like cars) do not. "The bottom line is that, while it remains difficult to predict how far or for how long the various 'transitory' factors will boost inflation, there is increasing evidence that inflationary pressures are broadening out, underlining that inflation will remain elevated for much longer than Fed officials expect," the firm explained on Wednesday in a note to clients.

As bad as that sounds, it could have been worse. Imagine if progressive Democrats had been successful in further juicing consumer demand by getting jobless benefits expanded and extended on a permanent basis. Or if they had somehow pushed Congress to pass a $10 trillion infrastructure plan instead of one around $1 trillion.

The current level of inflation is persuading many on Wall Street that the Fed will start raising interest rates sooner than expected. Goldman Sachs recently told clients it was "pulling forward our forecast for the Fed's first rate hike by one full year to July 2022. ... We expect a second hike in November 2022 and two hikes per year after that."

No president or incumbent party likes it when the Fed starts a tightening cycle in an election year given the risks rising rates present to the stock market and economy. The recent gubernatorial elections in New Jersey and Virginia gave Democrats plenty to worry about next year. Inflation is now giving them even more. And those concerns are likely here to stay.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

‘They’re nervous about playing the game’

‘They’re nervous about playing the game’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

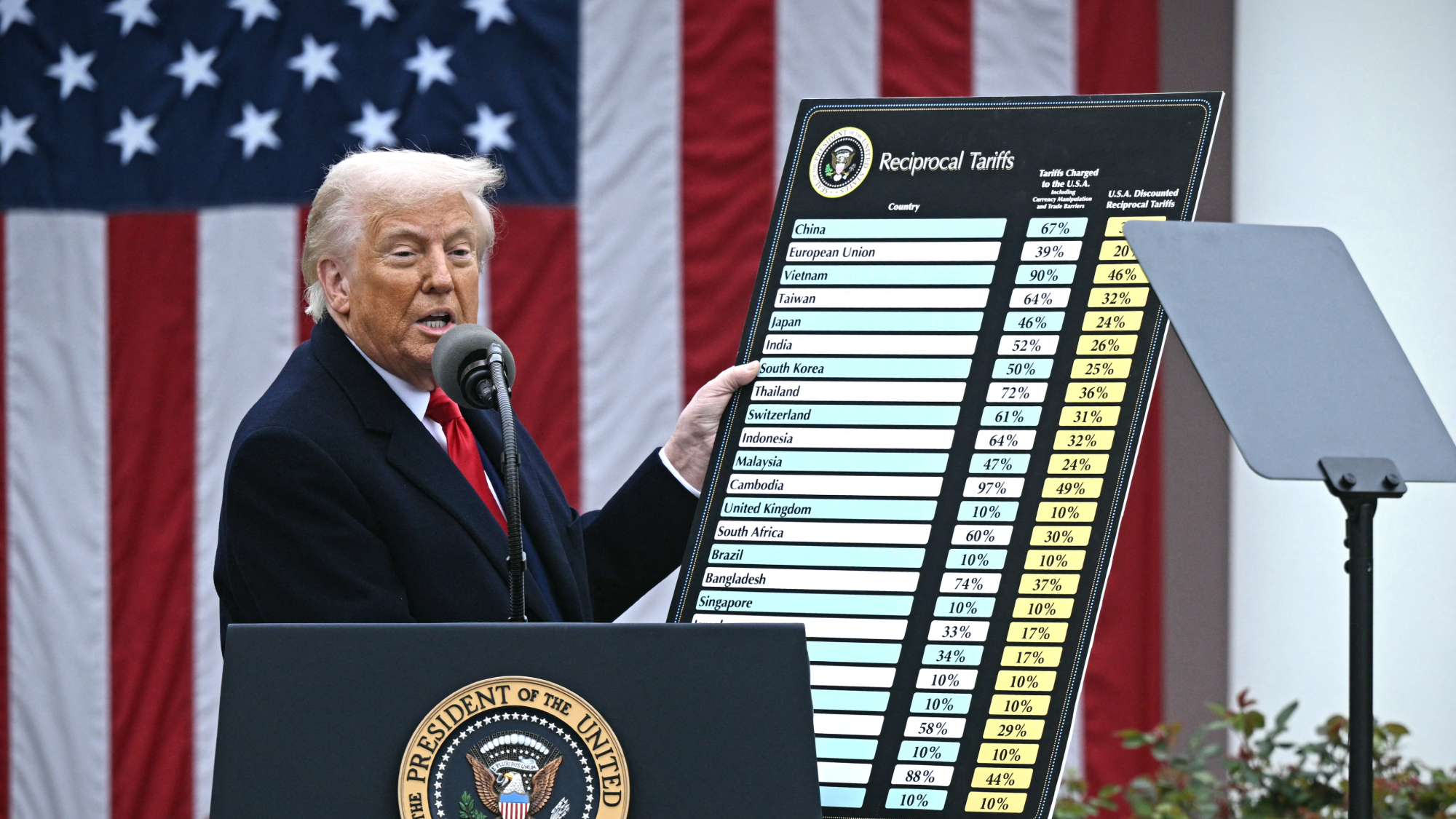

Tariffs: Will Trump’s reversal lower prices?

Tariffs: Will Trump’s reversal lower prices?Feature Retailers may not pass on the savings from tariff reductions to consumers

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

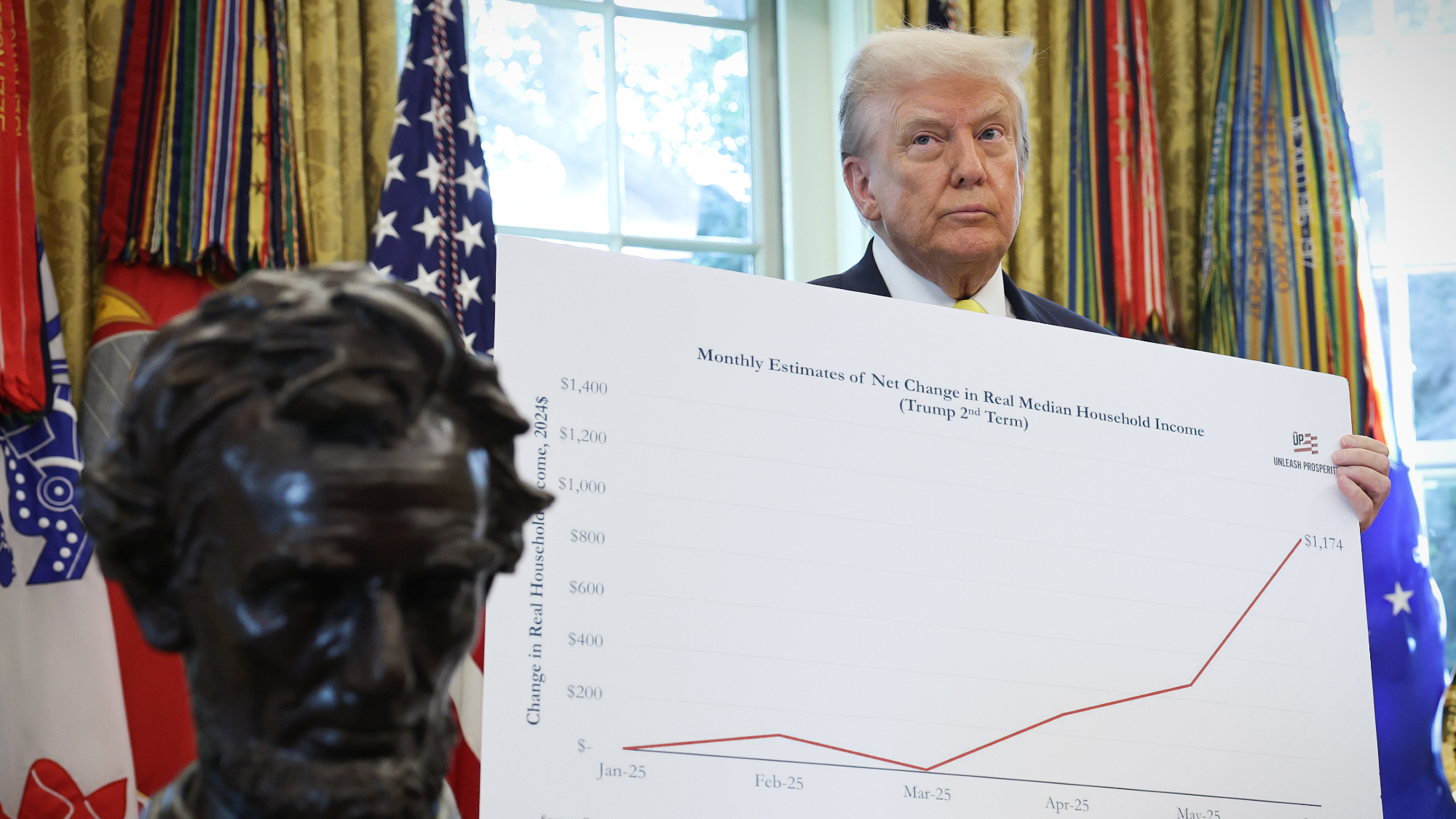

Inflation derailed Biden. Is Trump next?

Inflation derailed Biden. Is Trump next?Today's Big Question 'Financial anxiety' rises among voters

-

Trump picks conservative BLS critic to lead BLS

Trump picks conservative BLS critic to lead BLSspeed read He has nominated the Heritage Foundation's E.J. Antoni to lead the Bureau of Labor Statistics