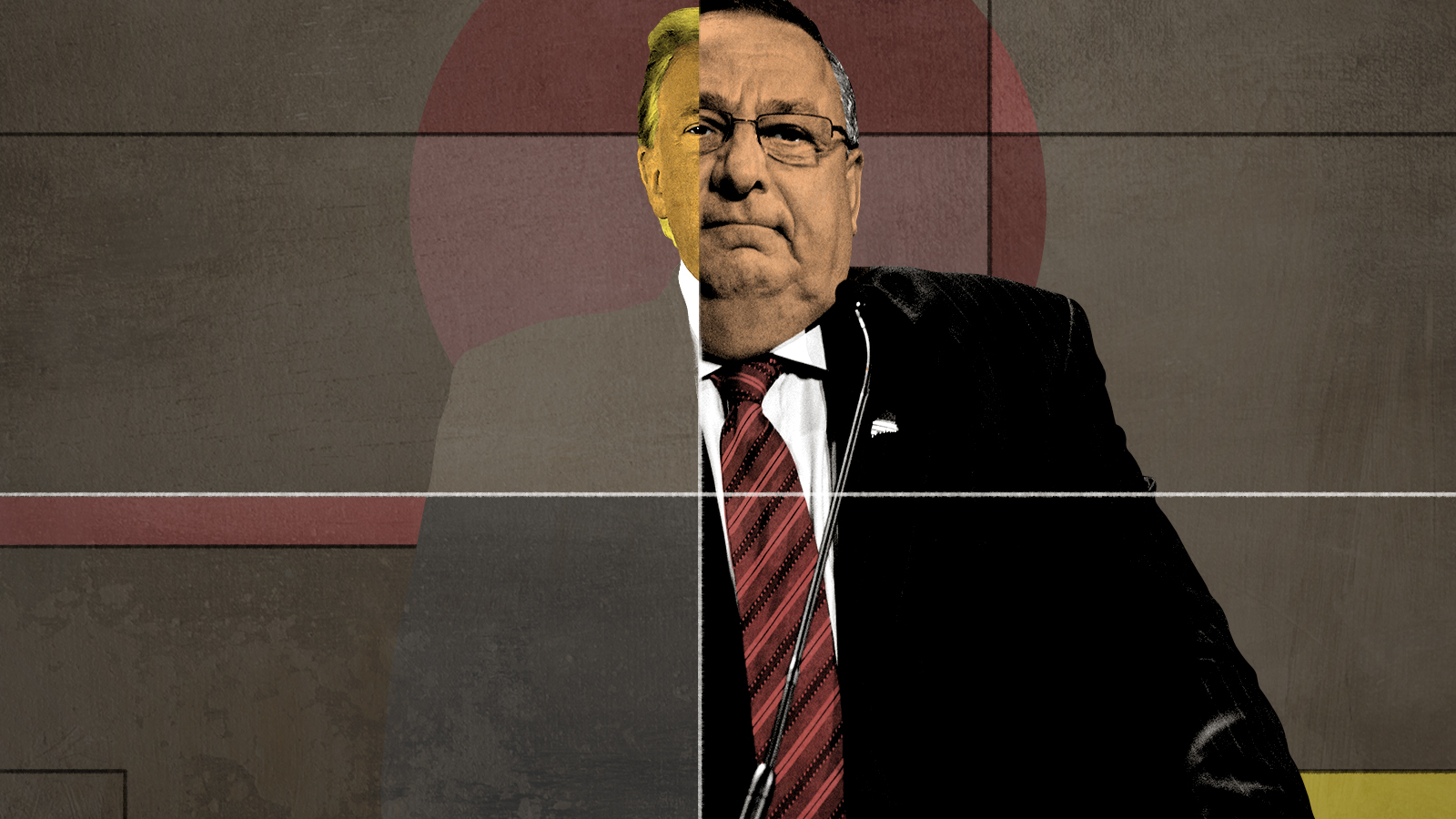

Maine's Paul LePage, the once — and future? — Trump

Trump's political prototype is running for office again. What does it mean?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Stop me if you've heard this one before: A candidate perhaps most notable for his success in business emerges from the surprisingly large number of other serious candidates in the Republican primary to win the nomination. He then wins the general election without a majority of the vote, motivating a new wave of interest in changing election procedures among liberals. His tenure in office is devoted mostly to implementing a pretty standard Republican agenda, although you'd never know it from the ridiculous and occasionally offensive things he says and the outraged media coverage of his antics. After leaving office, he retreats to Florida, where he begins plotting how he will regain the position he once held.

I am speaking, of course, about Paul LePage, the former governor of Maine, who will again be on the ballot for that office this Election Day. Why — who did you think I had in mind?

LePage was, more than any other politician in the Tea Party wave of 2010, Trump's John the Baptist, showing that there was a market for a politician who would say anything and everything that came to his mind and whose greatest commitment was épater les libs. It is not clear to me that, for example, attributing the heroin epidemic to "guys with the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty" who come to the state and "half the time they impregnate a young white girl before they leave" actually addressed the heroin epidemic in any way, but it did express an attitude — and make the right people mad — as well as anything could.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's not surprising that a prophet of Trumpism emerged out of Maine, a strange state in a number of ways, and not just in the Stephen King sense. It is the oldest and whitest state in the union; it is also one of the least religious. A key part of Trump's support in the 2016 GOP primary came from those who seldom or never attend religious services, and it's not a coincidence that his clearest predecessor emerged in northern New England, where a sense of American decline is constantly present and religion hardly matters.

The state is divided into two parts, more or less. The first is greater Portland, which has grown and flourished as the city at its heart has gentrified, and the coast where people summer; the New York Times columnist Ross Douthat once described it as "a long bustling stretch of Bobo prosperity, a string of restaurants and art galleries and bookstores and antique stores and coffee shops." The second is, well, the rest of the inhabited part of the state, a bunch of slowly dying farms and mill towns that have suffered population decline for decades now. (The remainder of the state beyond that is, of course, uninhabited, but trees, moose, mosquitoes, and the wendigo do not have the franchise.) And the two parts are moving in opposite directions politically — Biden improved on Clinton's showing in 2016 in Portland and its suburbs, while Trump did slightly better in more rural parts of the state in 2020.

How do LePage's chances look this year? Pretty good, I think. There's been hardly any polling of the race, but a Spectrum News/Ipsos poll from September found that more Maine voters supported LePage's decision to run for governor again than opposed it, and the national environment has gotten much worse for the Democrats since then.

LePage was once outside of the mainstream of the GOP, not in policy but in presentation. Now he's so conventional that he seems likely to win an election, not because of any traits unique to Paul LePage, but because he is the candidate with an R after his name. But he is still who he is, and maybe the opportunity to vote against him will give the Democrats a bit of motivation they wouldn't otherwise have.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And, if he wins, will that victory again herald a Trump presidency? Here I'm more doubtful. For one thing, Trump does not have the advantage of being on the ballot in 2022. For another, the demographics in Maine are enough unlike those of America as a whole that I'm uncomfortable extrapolating. This cuts both ways. The Democrats' increasing struggles with minority voters will not be as important in Maine since there are so few minority voters; on the other hand, the age of Maine's population gives the Republicans an advantage they lack on the national level.

LePage isn't Trump. (No one else can ever be Trump.) But, as a representative of Trumpist spirit, he's about as close as there is. And whether he wins or loses in November, his return to the political scene in Maine is a reminder that Trump didn't come out of nowhere, that those same forces that made him president once might make him president again, sure, but they'll also continue to be active in downballot races all over the country — especially those parts of the country where his message resonated most.

Steve Larkin is a writer from the state of Maine. His writing has appeared in The Week, the Catholic Herald, and other publications.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant US intelligence

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rolls

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rollsSpeed Read A Trump-appointed federal judge rejected the administration’s demand for voters’ personal data

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders