Were Supreme Court confirmations always so ugly?

What history can tell us about the increasingly polarized Supreme Court confirmation battles

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Washington is gearing up for another Supreme Court confirmation battle, this time to replace liberal Justice Stephen Breyer. Since Democrats control the White House and the Senate, albeit narrowly, President Biden may be able to get his nominee —a Black woman, he has pledged — onto the Supreme Court with relative ease. Or not.

Recent confirmation battles have not been for the faint-hearted. Liberals and conservatives point to different beginning and inflection points in the great judicial wars of the past couple decades, but few people disagree that the partisan rancor over Supreme Court picks is real and intense.

So how did Supreme Court confirmation fights become the knock-down, drag-out public spectacles we seem to have come to expect? There are a lot of reasons, among them high political polarization, deep-pocketed judicial advocacy groups, years of bad blood between aging senators, the growing power of the Supreme Court — and television.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When did things start to get ugly?

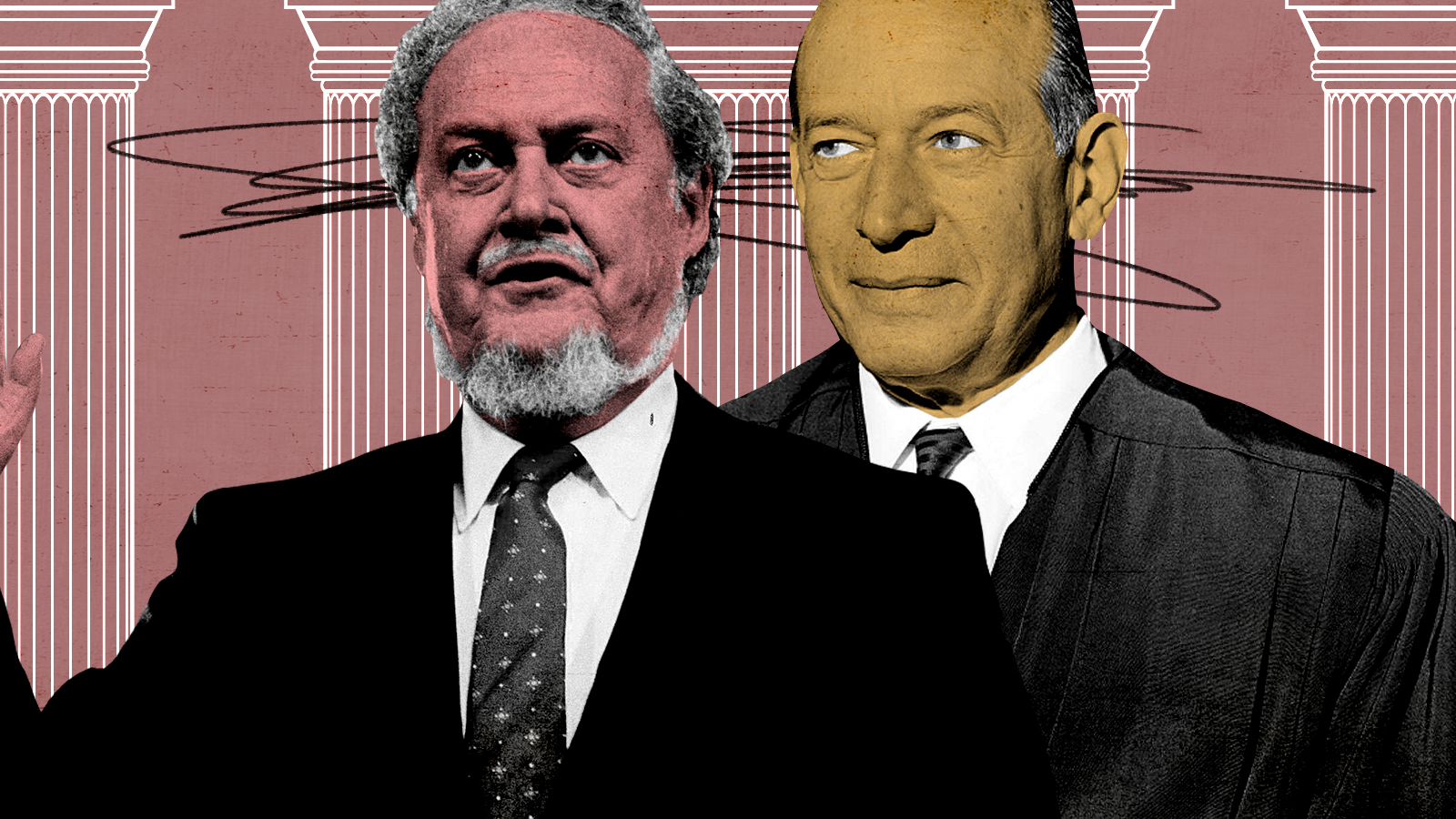

Many conservatives point to the failed confirmation of Robert Bork in 1987.

"Bork's extensive judicial record and writings championing a strict constructionist view of the Constitution came under fire almost immediately," Barbara Maranzani writes at the History Channel. "When the Reagan White House failed to mount a strong defense of Bork for more than two months, the confirmation process grew increasingly contentious," and outside groups jumped into the fight. Bork was eventually defeated 42 to 58, prompting the new verb "borking."

That defeat "still angers conservatives who believe Bork was a brilliant jurist who was unfairly maligned," USA Today reports. President Ronald Reagan next tapped Douglas Ginsburg, who withdrew after it emerged he had smoked marijuana, and then won easy confirmation of Justice Anthony Kennedy, a key swing vote until his retirement in 2018.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Does everyone agree Bork was the ignition point?

No. "Well before the term 'Borked'" entered our lexicon, "the nomination of Abe Fortas — already a sitting justice — to become chief justice in 1968 established the template for the bitter confirmation battles mimicked by later generations," Michael Bobelian argues in the Los Angeles Times. Sen. Strom Thurmond (R-S.C.) led an ambush of Fortas, including the only successful filibuster of a Supreme Court nominee, and Fortas resigned from the court under pressure in 1969.

"Contrary to the prevailing wisdom, it was this imbroglio — and not Bork's nomination in 1987 — that triggered the modern confirmation wars, transforming the selection of justices into the hyper-politicized, high-stakes contest we live with to this day," Bobelian writes.

The Fortas fight ended a "70‐year near‐perfect run of nominations," the Cato Institute's Ilya Shapiro says. "Until that point, most justices were confirmed by voice vote, without having to take a roll call. Since then, there hasn't been a single voice vote."

What happened after Bork?

David Souter was confirmed with little drama in 1990, but the 1991 confirmation of Justice Clarence Thomas was a spectacle, thanks to late-breaking sexual harassment allegations from a former subordinate, Anita Hill. Thomas was confirmed, 52-48, the narrowest margin in 100 years. Conservatives were furious and Thomas, who is Black, called the hearings a "high-tech lynching."

The next few justices — Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Breyer, John Roberts, Samuel Alito, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor — were confirmed by comfortable margins, with Alito the only justice getting fewer than 60 votes. Then things got ugly again.

When conservative Justice Antonin Scalia died suddenly in early 2016, President Barack Obama nominated Judge Merrick Garland, a moderate, but Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) blocked Garland from even getting a committee hearing. President Donald Trump filled the seat with conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch a year later, 54-45, after McConnell carved out a Supreme Court exception to the filibuster.

"McConnell's action created a deep and lingering bitterness among Democrats, who believe Obama was robbed of his right to appoint a justice," USA Today notes. The brawl to confirm Justice Brett Kavanaugh in 2018, centered around another late-breaking sexual assault allegation, left Republicans livid. His 50-48 confirmation was followed two years later by the rushed 52-48 confirmation of conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett to replace Ginsburg, who died less than two months before the 2020 election.

Democrats seethed over Barrett replacing Ginsburg eight days before Trump was defeated, especially given McConnell's stated let-the-voters-decide rationale for blocking Garland.

Were Supreme Court confirmations milquetoast before the Fortas fight?

Not always. Modern presidents are actually faring better than their 19th century predecessors in getting their nominees seated. Since 1789, presidents have formally submitted 164 nominations for the Supreme Court, and the Senate confirmed 127 of them — 30 failed, seven declined to serve, according to the Senate.

And bitter battles are almost as old as the Supreme Court itself. George Washington had one of his nominees, John Rutledge, rejected in 1775 because the Senate didn't like his opposition to a treaty with Britain. President John Tyler saw four of his five Supreme Court nominees rejected by a Senate controlled by the Whigs, who had kicked Tyler out of the party within a year of him taking office. Anti-Semitism played a significant role in the 1916 confirmation fight for Justice Louis Brandeis, whose eventual approval as the first Jewish Supreme Court justice in 1916 followed the first-ever public confirmation hearing.

The narrowest Supreme Court confirmation record is still held by Stanley Matthews, nominated by his lame-duck father-in-law President Rutherford B. Hayes in January 1881. Matthews was confirmed in a 24-23 vote, but only after being renominated by Hayes' successor, James Garfield, Sheldon Gilbert recounts at the National Constitution Center. Among the reasons for the bipartisan opposition to Matthews were his close ties to Hayes, perceived conflicts of interest, his role persuading a congressional committee to make Hayes president over popular vote–winner Samuel Tilden after the 1976 election, and Democratic frustration at 20 straight years of Republican presidents locking them out of the Supreme Court.

"Critics claimed that Matthews' narrow confirmation to the Supreme Court's would irreparably tarnish the court's reputation," Gilbert writes. "For example, Harper's Weekly featured a cartoon by famed political cartoonist Thomas Nash showing the Supreme Court's 'prestige' had collapsed under the weight of Matthews and his 'one vote' margin."

So why do Supreme Court fights feel so much more contentious now?

"It's a well-debunked myth that Supreme Court nominations have only become partisan over the last few decades," Steve Vladeck said at Just Security. But starting with the Bork nomination, "the merits of (and opposition to) his confirmation were litigated in public — on television, on the radio, and in the press. More than any nomination beforehand, the Bork nomination galvanized ordinary people to care about the Supreme Court — and to care about how justices were chosen, for what reasons, and by whom."

"Things changed in the 1980s, not coincidentally when the hearings began to be televised," says Cato's Shapiro. Through much of the 20th century, senators asked perfunctory questions in confirmation hearings, if they spoke at all, but "now all senators ask questions, especially about key controversies and fundamental issues, but nominees largely refuse to answer, creating what Elena Kagan 25 years ago called a 'vapid and hollow charade.'"

"It must be a surreal experience, having run an American Ninja Warrior course to win a life of quiet contemplation and oracular pronouncements," Shapiro adds. "Or, as President Trump's first White House Counsel Don McGahn put it, 'it's a Hollywood audition to join a monastery.'"

Surely preening senators aren't the only cause?

It's important to note that not all confirmation fights are bitter brawls. Supreme Court nominations are essentially about two major things: "The nominee's suitability for the court and the impact the nominee would have on the court," Vladek says. "Sometimes, nominations go smoothly because there's just no question as to suitability. Sometimes, nominations go smoothly because the nominee, if confirmed, would not actually move the Court that far in any particular direction."

The Bork fight was so contentious largely because it would have replaced a moderate with a conservative; Garland would have replaced the conservative Scalia; and Thomas did replace the liberal Thurgood Marshall, Vladek notes. "To my mind, at least, it should still be possible to have relatively uneventful nominations in cases that don't portend such an impact to the court's ideological balance."

Confirmation fights are as old as the court, but the nature of them has changed over the years, Shapiro argues. Given that Republicans and Democrats have come to adopt "essentially incompatible judicial philosophies," he adds, "it's impossible for a president to find an 'uncontroversial' nominee."

Finally, the stakes are just higher. As Congress "has decided to self-neuter," as Sen. Ben Sasse (R-Neb.) put it during Kavanaugh's confirmation brawl, the Supreme Court has grown in power. "This transfer of power means people yearn for a place where politics can be done," he said. "And that's why the Supreme Court is increasingly a substitute political battleground for America," to the detriment of the court and the nation.

"Another reason why filling each vacancy is such a big deal is that justices now serve longer," Shapiro notes. "before 1970, the average tenure of a Supreme Court justice was less than 15 years. Since then, it's been more than 25. The life expectancy of justices once confirmed has grown from about eight years at the beginning of the Republic to 25–30 today. Justices appointed at or before age 50, like Roberts, Kagan, Gorsuch, and Barrett, are likely to serve 35 years, or about nine presidential terms."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.