An0m: the surveillance sting of the century

Simon Parkin reports on the encrypted messaging service used by criminals around the world

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

An encrypted phone used by criminals around the world to conduct their operations in the shadows had just one flaw: it had been conceived, built, marketed and sold by police, who were monitoring every text exchange.

The rain pattered lightly on the harbour of the Belgian port city of Ghent when, on 21 June 2021, a team of professional divers slipped below the surface into the emerald murk. The Brazilian tanker, heavy with fruit juice bound for Australia, had already crossed the Atlantic, but its journey wasn’t halfway done as the divers felt their way along its hull. They were looking for the sea chest, an inlet below the waterline through which the ship draws seawater to cool its engines.

Tucked inside, they found what they were hunting for: three long sacks, wrapped in a thick plastic bag. When the Belgian police opened the first, a stack of bricks of cocaine slid out. Had this cargo reached Australia, the haul would have been worth more than A$64m (£34m).

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Smuggling tens of millions of dollars of Class A drugs across the ocean requires total secrecy and a significant amount of international logistical coordination. But the police knew about the alleged plot thanks to intelligence gleaned from a device that had, since its launch in 2018, become something of a viral sensation in the global underworld.

An0m, as it was called, looked like any off-the-shelf smartphone, but it could not be bought in a shop or on a website. First you had to know a guy, then you had to be prepared to pay: $1,700 for the handset with a $1,250 annual subscription, an astonishing price for a phone that was unable to make calls or browse the internet.

Almost 10,000 users around the world had agreed to pay, not for the device so much as for an application installed on it. Opening the phone’s calculator allowed users to enter a sum that functioned as a kind of numeric open sesame to launch a secret messaging application.

The people selling the phone claimed that An0m was the most secure messaging service in the world. Not only was every message encrypted so that it could not be read by a digital eavesdropper, it could be received only by another An0m phone user. Moreover, An0m could not be downloaded from any of the usual app stores.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Users’ confidence in An0m was, it seemed, bolstered by some novel functionality included on every device. In the past, phones marketed to hyper security-conscious users were sold with the option to remotely wipe the device’s data. This would enable, say, a smuggler to destroy evidence even after it had been collected. But police had started to use Faraday bags – containers lined with metal that would prevent a phone from receiving a kill signal. The An0m phone came with a workaround: users could set an option to wipe the phone if the device went offline for a specified amount of time. Users could also send voice memos in which the phone would automatically disguise the voice.

An0m was the ideal channel to arrange the passage of A$64m of cocaine across the world. It was not, however, a secure phone app at all. Every message sent on the app since its launch in 2018 – 19.37 million of them – had been collected, and many of them read by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) who, with the FBI, had conceived, built and sold the devices.

On 7 June 2021, more than 800 arrests were made around the world, all of people who had in some way fallen under suspicion thanks to these devices that sent information to the AFP. In Belgium, two weeks later, the divers did not have to hunt for the sacks of cocaine for long; they knew where to look. Operation Ironside (or Operation Trojan Shield, as it was known in the US) was the largest coordinated law enforcement effort in Australian history.

Richard Chin, head of transnational operations in the AFP, had taken to calling 7 June “Big Bang”. If all went to plan, the operation had the potential to reshape the criminal world. Big Bang’s targets constituted an array of underworld figures: mobsters, bikers, neighbourhood drug barons, whose alleged crimes ranged from money laundering to attempted murder. What they had in common was their choice of texting app.

The scheme was seeded ten years earlier, in Vancouver. There, in 2008, Vincent Ramos, a young entrepreneur who started out as a bathtub salesman, founded Phantom Secure, a telecoms company that promised users absolute privacy. Phantom Secure’s phones were BlackBerries modified to remove the camera, microphone and GPS tracking software, and installed with a remote-wipe feature. Every message sent from one device to another was encrypted and routed through servers in Panama and Hong Kong.

On Phantom Secure’s website, the phones were marketed to the “sophisticated executive”. While it was company policy not to collect clients’ names, Ramos became aware that his customers were not, in fact, legitimate businessmen, but criminals drawn by the promise of a means to communicate beyond the reach of the law. Ramos made no checks on clients. He did not believe it was his responsibility: he was a mere humble salesman of aftermarket BlackBerries – albeit one who drove a Lamborghini.

In 2015, the San Diego office of the FBI began investigating Owen Hanson, a former American football player who had turned to drug trafficking after the collapse of his real-estate business. Hanson was a Phantom Secure customer who idolised Hollywood gangsters, had a silverplated AK-47 stamped with the Louis Vuitton logo, and owned a restaurant with a backroom he referred to as the “wise-guy room”.

An undercover FBI agent gained his trust and was given a Phantom Secure phone. In acquiring one for the first time, the FBI had gained access to the criminal equivalent of WhatsApp: a messaging service filled with accumulating piles of digital evidence. By the time of Hanson’s arrest in 2015, he regularly shipped cocaine to Australia for $175,000 a kilogram. Two years later, Hanson was imprisoned for 21 years on charges of drug trafficking and racketeering. The logistics were planned on Phantom Secure phones, devices that had come to dominate the Australian criminal market.

The FBI now began a joint venture with the AFP to infiltrate the global Phantom Secure network. With the help of one of Phantom Secure’s distributors – an individual who had agreed to become a confidential source–the FBI arrested Ramos in 2018. They offered him a deal: the possibility of leniency in sentencing if he agreed to place a backdoor in the Phantom Secure network. Either because ofalack of technical know-how, or fear for his safety, Ramos refused, and was sentenced to nine years in prison. Without an “in”, the FBI was left with no choice but to shut down the Phantom Secure servers. The disappearance of the platform left a gap in the market. Agents reasoned: what if, rather than attempting to infiltrate an existing encrypted phone network, we built our own?

To launch a desirable encrypted phone product, the AFP and FBI not only needed to think like a tech start-up, they effectively had to become one. “We positioned ourselves as a small, bespoke brand coming into the organised crime marketplace,” says Chin.

The aim was to assure prospective clients of the product’s “security, privacy and anonymity”. The An0m application and bespoke operating system were provided by a former distributor of the Phantom Secure phones, whom the FBI recruited in exchange for a chance of a reduced sentence. The source was paid $180,000 by the FBI in salary and expenses, and built “a master key” that, the FBI explained in court documents, “surreptitiously attaches to each message and enables law enforcement to decrypt and store the message as it is transmitted”. Every message sent via An0m was effectively bcc’d to the police.

Next, the AFP began a grassroots marketing campaign, identifying influencers within criminal subcultures. One was Hakan Ayik – now known as Hakan Reis – a member of a gang responsible for smuggling an estimated $1.5bn of drugs into Australia every year. Reis, cartoonishly muscular and often photographed topless and flexing, had fled Australia in 2010, and became An0m’s first official user and influencer. His unwitting support of the AFP’s efforts directly resulted in the arrests of many criminal associates, Chin says. (Reis is currently believed to be hiding in Turkey; the AFP has expressed “significant concerns for the safety and welfare of [his] wife and two children”.)

As soon as An0m devices were in the wild, the AFP began to receive messages sent via the app. “On a daily basis, we were receiving messages about drug distribution, drug importation into Australia and elsewhere,” says Chin. Some users felt so confident in its security that they dispensed with euphemisms, naming drugs and weight measurements. An0m’s success in Australia was soon replicated overseas, with distributors in Mexico, Turkey, the Netherlands, Finland and Thailand – as well as, allegedly, at least one British citizen, James Flood, believed to be living in Spain.

As An0m’s reach expanded to 12,000 devices in more than 90 countries, Chin and his colleagues’ net was forced to expand accordingly. The operation quickly revealed the sophistication with which major criminal organisations run their communication policies. The millions of decoded messages presented the AFP with a pressing ethical dilemma: when to interfere to prevent a single planned crime, and when to allow crimes to take place, preserving the integrity of the wider operation.

Eventually, the AFP decided to intervene primarily in instances where there was a“serious chance someone might get killed”, Chin says. During the 18 months leading up to 7 June, the agency acted on 21 such threats to life. In March 2021, An0m’s active user base suddenly tripled after Belgian police dismantled Sky Global, a rival service. The surge in popularity caused a drastic increase in the amount of information Chin and his team had to parse, increasing the potential threats to life to unmanageable proportions for the AFP.

The date for Big Bang was set. To minimise the risk of exposure, few individuals at the agency had been told about Operation Ironside. When, a week before Big Bang, wider personnel at the AFP were informed of what the team had been working on, there was widespread shock. “I was amazed at the scale,” one police officer involved in Sydney raids tells me.

Although the majority of raids took place on 7 June, police activity leading up to that day led some users to suspect their phones might be compromised. Some listed their devices in local classified pages. Most, however, continued to send messages unwittingly. As a result of Operation Ironside, by 25 July, 693 search warrants had been issued, 289 alleged offenders charged, and A$49m in cash, 4,788kg of drugs and 138 firearms and weapons seized in Australia alone. Six illegal drug labs had been dismantled.

As mainstream phone providers and app makers from WhatsApp to Signal have increasingly touted end-to-end encryption as a key selling point, police everywhere have pushed for the introduction of backdoors that allow them to access messages to investigate alleged crimes. A legal case between the FBI and Apple, whereby the former demanded the company create a tool that would allow it to access messages on an iPhone 5C to use in its case against the perpetrators of the San Bernardino terrorist attack, became a touchpoint in a debate over civil liberties in a digital world. The An0m network represented a creative sidestep: why debate tech companies on privacy issues through costly legal battles if you can simply trick criminals into using your own monitored network?

Now that the workings have been revealed, however, An0m is a trick that could surely never be repeated in the world of organised crime. The revelations will push criminals away from technology, even if it makes their work more laborious and slow-moving. Besides, the AFP estimates that messages harvested via An0m represent only a fraction of criminal communications sent in Australia during the 18 months An0m was on the market. “It is true that the groups will adapt accordingly,” says Chin. “I guess all I can say is that we have skills and capabilities to adapt, too.”

This article was first published in The Guardian. © Guardian News and Media Limited 2021

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

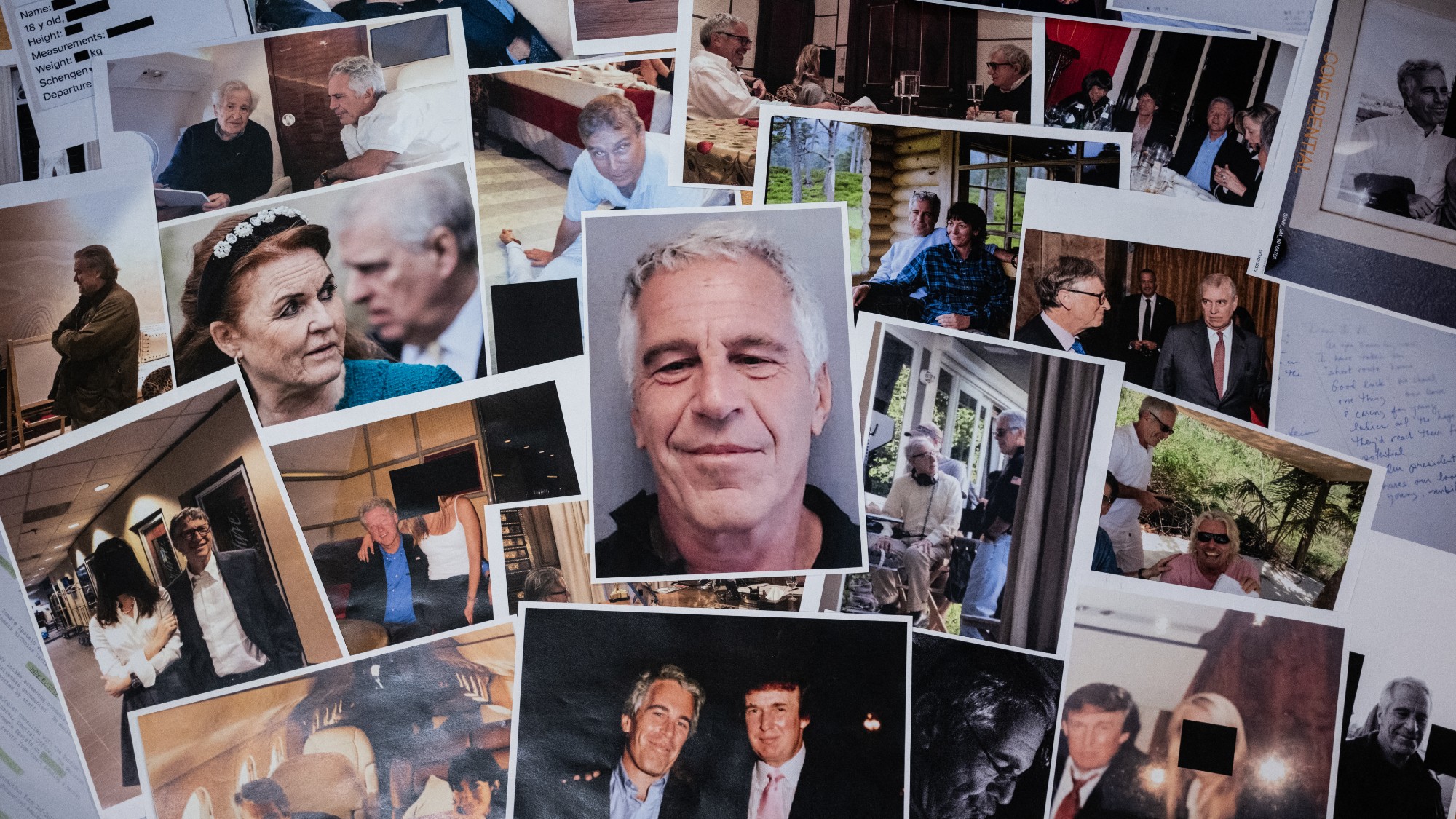

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing world

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing worldIn the Spotlight Trove of released documents paint a picture of depravity and privilege in which men hold the cards, and women are powerless or peripheral

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

How the Bondi massacre unfolded

How the Bondi massacre unfoldedIn Depth Deadly terrorist attack during Hanukkah celebration in Sydney prompts review of Australia’s gun control laws and reckoning over global rise in antisemitism

-

Diddy: An abuser who escaped justice?

Diddy: An abuser who escaped justice?Feature The jury cleared Sean Combs of major charges but found him guilty of lesser offenses

-

Crime: Why murder rates are plummeting

Crime: Why murder rates are plummetingFeature Despite public fears, murder rates have dropped nationwide for the third year in a row

-

The Sycamore Gap: justice but no answers

The Sycamore Gap: justice but no answersIn The Spotlight 'Damning' evidence convicted Daniel Graham and Adam Carruthers, but why they felled the historic tree remains a mystery

-

What are grooming gangs? The UK scandal, explained

What are grooming gangs? The UK scandal, explainedThe Explainer Three-year inquiry will ‘root out this evil once and for all’, says home secretary

-

NCHIs: the controversy over non-crime hate incidents

NCHIs: the controversy over non-crime hate incidentsThe Explainer Is the policing of non-crime hate incidents an Orwellian outrage or an essential tool of modern law enforcement?