H5N1: bird flu in mammals stoking fears of human ‘spill-over’

Avian flu in foxes, otters and mink has led to calls for greater international action

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The spread of bird flu to mammals, including foxes and otters in Britain, has stoked fears that the virus could one day pass between humans in a pandemic like Covid-19.

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) maintains that the avian influenza H5N1 virus is still primarily a disease of birds, but experts around the world are “looking at the risks of it spilling over into other species”, said the BBC.

While some think the chance of human-to-human transmission is low, an outbreak among mink in Spain has caused particular concern.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How bad is the current avian flu outbreak?

The current outbreak of avian influenza is regarded as the worst ever in Britain, in Europe, and across the entire northern hemisphere.

According to the BBC, the virus has “led to the death of about 208 million birds around the world and at least 200 recorded cases in mammals”.

It has been found in grizzly bears in America, as well as dolphins. More than 700 seals were found dead in December in the Caspian Sea, near to the site of a large outbreak of H5N1 in wild birds months earlier.

How does avian flu spread to mammals?

In the UK, the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) has tested 66 different species of mammals, and found four otters and five foxes were positive for avian flu.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

While there is currently no evidence that bird flu can spread from fox to fox or otter to otter, “genetic sequencing of the virus from an October 2022 outbreak on a mink farm in Spain suggests the animals were infected with a new variant of H5N1 that could spread between mink”, said New Scientist.

Munir Iqbal, from the Pirbright Institute, told the magazine that more investigation is needed to confirm mammal-to-mammal transmission.

It has nevertheless “reignited long-smouldering fears that H5N1 could trigger a human pandemic”, said Science magazine.

Are these fears well founded?

Humans can catch bird flu. There have been six confirmed infections in the latest worldwide wave, including one death. But there is currently “no evidence that the virus can pass between humans”, the i news site said. The latest cases were all acquired “directly from close contact with poultry or other birds”.

“Yet researchers are worried that if the H5N1 virus mutates to transmit between mammals, it could soon be able to jump between human hosts,” said the New Scientist.

The discovery of H5N1 in the two UK mammal species has triggered a move to more “targeted surveillance and testing of animals and humans exposed to the virus in the UK”, said the BBC.

Prof Ian Brown, APHA’s director of scientific services, told the broadcaster he was “acutely aware of the risks” of bird flu becoming a pandemic like Covid-19. “We do need globally to look at new strategies, those international partnerships, to get on top of this disease,” he said.

Marion Koopmans, head of the department of virology at the Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam and a member of the World Health Organization team charged with tracing the origins of Covid, said: “We are playing with fire.”

If it can spread between mammals, there is an “opportunity for a virus from the risk list to pick up mutations which could make it transmissible between humans”, she said. “It didn’t happen this time, and it may not happen, but this is one of the scenarios from which a new pandemic could originate.”

Where did the new virus come from?

Bird flu, mostly of a mild kind, has always existed in birds, particularly migratory waterfowl such as geese and ducks (songbirds are largely unaffected). However, a new form of the H5N1 virus emerged in Asia in the 1990s in intensive poultry farms, an ideal viral breeding ground.

This was first detected in Guangdong province, southern China, in 1996, and spread to chicken farms in Hong Kong a year later, where it killed six people. In 2005, the virus caused a large outbreak among wild birds in Lake Qinghai in China, where nearly 200 migratory breeds congregated near large poultry farms.

Since then, the virus has infected wild birds in Europe, the Middle East and North America, and now circulates the world most years, often infecting farmed birds. The latest outbreak hit the UK in October 2021.

How is the situation different this time?

With a reproduction number as high as 100 (each infected bird can infect about 100 others), the latest bout of H5N1 has spread exceptionally quickly. It is “highly pathogenic”: it causes respiratory problems and diarrhoea, and is often fatal.

In previous years, outbreaks in Britain have been caused by migratory waterbirds arriving from Europe and the Arctic in autumn and winter, bringing the virus with them; but outbreaks have historically fizzled out once those birds have left in the spring.

This time has been different. For the first time, H5N1 spread to Britain’s nonmigratory wild birds, possibly owing to a mutation in the virus. In particular, it has affected seabirds, which live in huge, dense colonies on Britain’s cliffs and islands, making it easy for the virus to take hold.

What is the government doing?

In October, the Department of Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) imposed a bird flu “prevention zone” across the whole of Great Britain: free-range birds were to be kept within fenced areas, and other strict biosecurity measures were imposed. In November, Defra ordered all poultry and captive birds in England to be housed indoors; free-range eggs will be relabelled “barn-laid”. Those who have had to cull flocks are being compensated.

But some have criticised a lack of urgency in the official response. As bird flu spread through the Farne Islands last summer, for instance, not a single bird was tested for the virus. Guidance on collecting birds has been criticised as “patchy”, resulting in decaying corpses being left on the islands for weeks.

Arion McNicoll is a freelance writer at The Week Digital and was previously the UK website’s editor. He has also held senior editorial roles at CNN, The Times and The Sunday Times. Along with his writing work, he co-hosts “Today in History with The Retrospectors”, Rethink Audio’s flagship daily podcast, and is a regular panellist (and occasional stand-in host) on “The Week Unwrapped”. He is also a judge for The Publisher Podcast Awards.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

Starmer vs the farmers: who will win?

Starmer vs the farmers: who will win?Today's Big Question As farmers and rural groups descend on Westminster to protest at tax changes, parallels have been drawn with the miners' strike 40 years ago

-

How 'corn sweat' has made summer in the Midwest worse

How 'corn sweat' has made summer in the Midwest worseUnder The Radar Lend an ear to this kernel of agricultural science.

-

Greece's deadly 'goat plague' threatens its trademark feta cheese

Greece's deadly 'goat plague' threatens its trademark feta cheeseUnder the Radar About 9,000 animals have already been culled amid outbreak of 'highly contagious' PPR virus

-

The growing thirst for camel milk

The growing thirst for camel milkUnder the radar Climate change and health-conscious consumers are pushing demand for nutrient-rich product – and the growth of industrialised farming

-

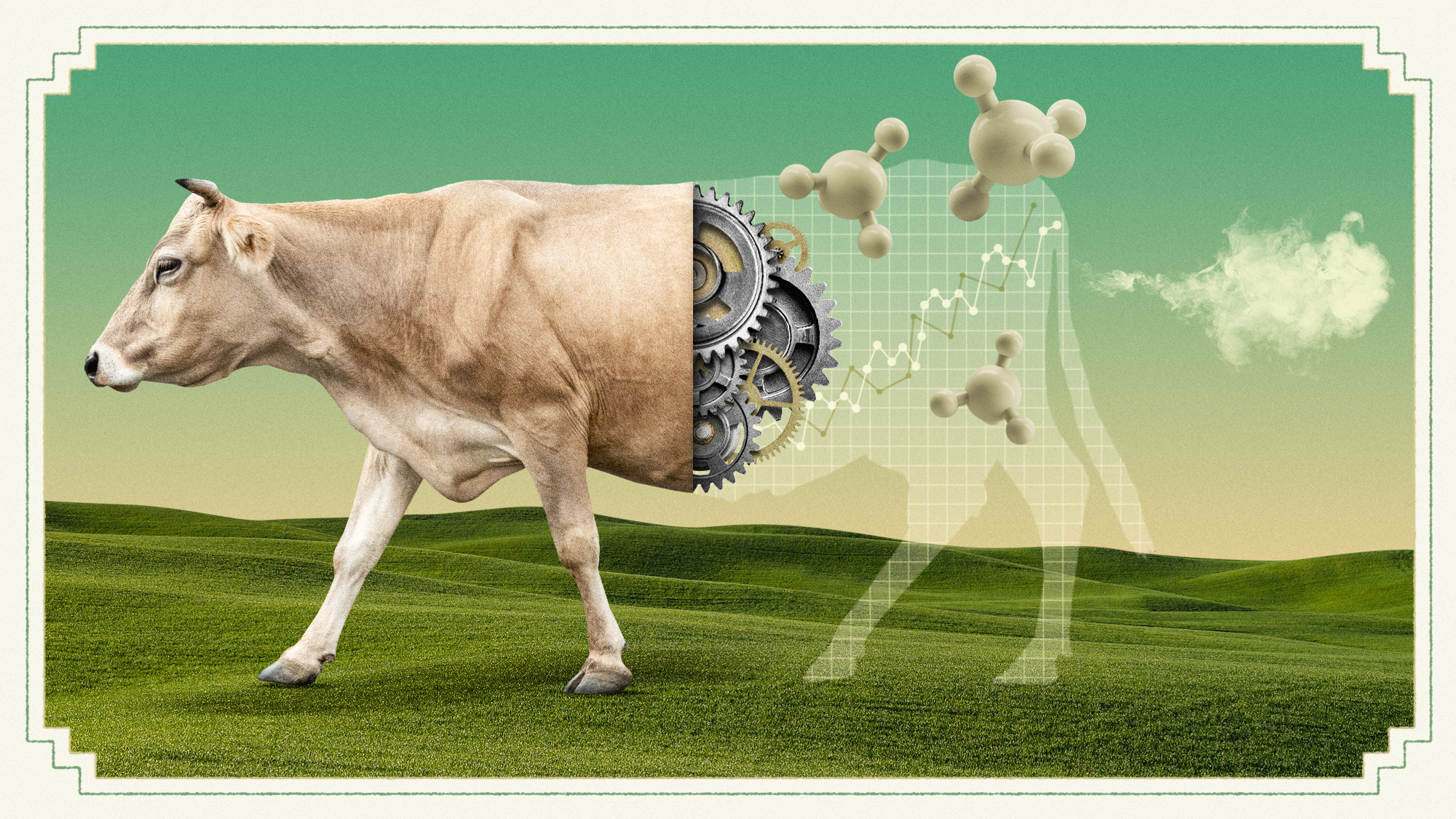

Why curbing methane emissions is tricky in fight against climate change

Why curbing methane emissions is tricky in fight against climate changeThe Explainer Tackling the second most significant contributor to global warming could have an immediate impact

-

How the EU undermines its climate goals with animal farming subsidies

How the EU undermines its climate goals with animal farming subsidiesUnder the radar Bloc's agricultural policy incentivises carbon-intensive animal farming over growing crops, despite aims to be carbon-neutral

-

Why are people and elephants fighting in Sri Lanka?

Why are people and elephants fighting in Sri Lanka?Under The Radar Farmers encroaching into elephant habitats has led to deaths on both sides