Dominic Cummings vs. Boris Johnson: the rise and fall of a ‘doomed’ relationship

The PM’s former right-hand man gave damning evidence against him today - so how did it come to this?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Dominic Cummings’ unfiltered account of what happened behind the scenes as the government grappled with the arrival of Covid-19 last year is likely to have been uncomfortable viewing for No. 10.

Once Boris Johnson’s closest adviser, Cummings has become his mortal enemy. But, even from the start, “it didn’t take a superforecaster to see that the relationship” between the prime minister and his chief adviser “was a disaster in the making”, says Daniel Finkelstein in The Times.

The Vote Leave tie

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The two men forged their working relationship back in 2016 during the Vote Leave campaign, which was orchestrated by Cummings and fronted by Johnson. Three years later, Cummings was one of Johnson’s first appointments after becoming PM.

Speaking in front of the House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee this March, Cummings revealed that he only agreed to work in Downing Street on the condition that Johnson doubled the country’s science budget and created a “high-risk, high-reward” research agency. Cummings apparently laid out the terms at a private meeting in his living room on the Sunday before Johnson took office, in July 2019.

Many other members of the PM’s top team were also former Vote Leave ministers and officials. A source who worked with both men on the Brexit campaign told Politico last year: “The whole operation is Dom. The whole of No. 10 is staffed by Dom proteges.” He was also widely regarded as the chief architect of the government’s policy agenda.

The personality clash

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Despite their formerly close working relationship, “the two men are very different”, says The Guardian. “Johnson courts approval; Cummings disdains it.” Yet the PM quickly came to rely heavily on his chief aide after taking over at Downing Street.

With “Brexit still hanging in the balance” when Johnson took over at Downing Street, the new leader “valued Cummings’ absolute commitment to the cause”, the newspaper continues. “But with no majority and a deeply divided party, he also knew he would need to fight a general election in short order - and Cummings is the consummate campaigner.”

Cummings, meanwhile, saw his new role as a once-in-a-lifetime chance to not only “get Brexit done” but to reshape the British state.

Critics note that Johnson has “always been more focused on amassing political power than on exercising it for particular purposes”, while Cummings “brims with ideas, not all of them practical”, says The New York Times. “He, too, resists ideological labels but is fuelled by an abiding suspicion for established institutions.”

Differences aside, the extent to which Johnson had become reliant on his then right-hand man became apparent in the wake of the revelation that Cummings had travelled 260 miles from London to Durham during the first Covid lockdown.

But while Cummings held on to his job despite widespread anger, he was “doomed from the start” to get booted out eventually, says The Times’ Finkelstein, who questions how both men failed to look to one another’s past to see how the future might map out.

“When Johnson hired Cummings to be his chief adviser, he must surely have noticed the regularity with which his relationships with his bosses had broken down,” Finkelstein writes. And “what is it in the career of Johnson that made Cummings think that his strengths lay in getting processes right, taking hard decisions and saying no to people?”

The departure

Cummings said in January 2020 that he intended to make himself “redundant” by the end of the year. But his exit came earlier, in November, as the PM attempted to “break the stranglehold of pro-Brexit campaigners on his No. 10 operation”, as the Financial Times reported at the time.

Senior government figures told the newspaper that Cummings and fellow Vote Leave veteran Lee Cain were suspected of leaking Downing Street’s plan for a second national lockdown at the end of October - a claim that both men have categorically denied.

The lockdown details were given to journalists by a source dubbed the “chatty rat” on 31 October. Two weeks later, on 13 November, Cummings was given his marching orders by Johnson.

Cain had resigned two days earlier, after the PM refused to make him chief of staff, in what was “seen by Tory MPs as a watershed moment”, according to the FT.

“Cummings feared that the new chief of staff role was a direct threat to his own power, hence his attempt to install his friend Mr Cain in the job,” the paper said. “But Tory MPs, tired of the dysfunctional No. 10 operation, told party whips that Mr Johnson had to break the knot with the Vote Leave team.”

Several sources also suggested that Johnson’s fiancee, Carrie Symonds, was pivotal in ensuring Cain did not get the job and had voiced concerns about the combative culture the two Vote Leavers instilled at No. 10.

The grudge

In the six months since Cummings’ departure, he has been nurturing a grudge against the people who he “blames for his demise”, says The Telegraph - and Johnson and Symonds are “at the top of the list”.

“He believes he and Boris Johnson had a pact,” a former colleague told the paper, “and that the prime minister broke that pact. The one thing in his career that he really cared about was getting into No. 10 and pursuing his personal projects.”

But Cummings had also “been living up to the ‘career psychopath’ tag coined by David Cameron perhaps as much as the political genius he claimed to be”, hiring and firing ministers’ media advisers and insisting he be the one to clear major announcements, The Telegraph adds.

As Cummings today gives his side of the story to MPs investigating the UK’s Covid response, he “will, as he’s always done, use Westminster as a stage to attack Westminster”, wrote the paper’s Tim Stanley this morning.

“He is an anti-politician playing politics, though this time he’s not only up against forgettable MPs, the hollow men he so despises, but one of the cleverest politicians of the age,” Stanley writes. “It’s Dom’s data vs. Boris’s magic.”

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

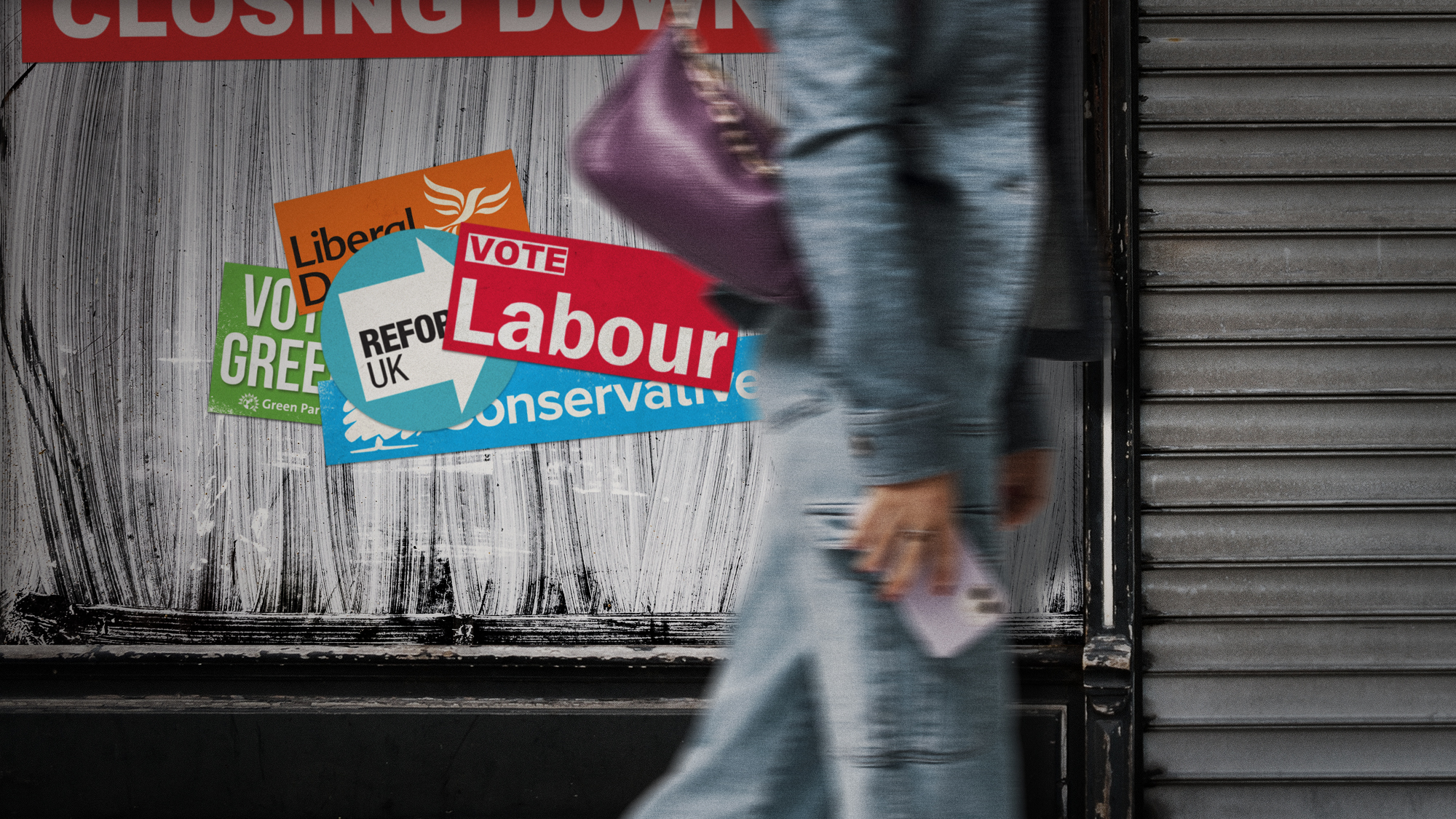

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Asylum hotels: everything you need to know

Asylum hotels: everything you need to knowThe Explainer Using hotels to house asylum seekers has proved extremely unpopular. Why, and what can the government do about it?

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

Behind the ‘Boriswave’: Farage plans to scrap indefinite leave to remain

Behind the ‘Boriswave’: Farage plans to scrap indefinite leave to remainThe Explainer The problem of the post-Brexit immigration surge – and Reform’s radical solution

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance

-

Is the G7 still relevant?

Is the G7 still relevant?Talking Point Donald Trump's early departure cast a shadow over this week's meeting of the world's major democracies