‘There is no end in sight’: everything to know about the great microchip shortage

Since late last year, there has been a severe shortage of microchips, which is now affecting industries across the world

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How bad is the shortage? “Never seen anything like it,” Tesla’s Elon Musk tweeted last month. Since late 2020, the world has been facing an unexpected dearth of microchips – the tiny integrated circuits that are nowadays found in practically every manufactured device with a battery or a plug – from toasters to TVs to airbags to fighter jets.

The scarcity was first seen in sophisticated consumer electronics: gaming consoles like the PlayStation 5 and the new Xbox have had big order backlogs; prices for computer graphics cards have shot up. But because semiconductor chips are so ubiquitous, a large number of industries have been affected.

The car industry has been hit hardest of all. Modern cars can easily contain 3,000 chips, and the shortage has slowed down vehicle assembly lines across the world: global output will drop by four million cars, nearly 5%, this year.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why is it happening?

At the best of times, chip supply chains are hard to maintain: it is an industry prone to gluts and shortages. Fabrication plants (“fabs”) for advanced chips are among the world’s most complex manufacturing facilities, costing tens of billions of dollars to build. Lasers print billions of transistors onto tiny areas of silicon wafers; it can take three to four months to turn a large silicon wafer into a useable batch of chips.

So the industry tends to swing between undersupply and oversupply, in what economists callapork cycle: as with breeding pigs, there are lags in production. Producers invest when prices are high and find they are left with too much capacity when it finally comes on stream. At present, however, the trend in the industry is of remorseless expansion: green tech, cloud computing, 5G, artificial intelligence, cryptocurrency, robotics – all these growth areas eat up chips. And the pandemic has helped to create the perfect storm.

What effect did the pandemic have?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It closed down many fabs temporarily. At the same time, the great increase in working from home, and the increase in demand for home entertainment, created a surge in demand for electronics. PC sales rose by 13% last year. In New York City alone, the department of education bought 350,000 iPads. Video calling meant that data centres needed more capacity.

And during the worst of the pandemic, car purchases plummeted. So while electronics companies bought up all available production capacity, car manufacturers cancelled their orders. But later, when the carmakers were ready to gear up production again, they found themselves at the back of the queue: microchip fabs can take up to six months to re-start production of specific types of chip.

How does this affect us?

The supply of cars for sale is set to be restricted later this year because of the shortage, the leading UK motor dealership Pendragon warned last week. With fewer cars to sell, prices will rise; and premium electronic features like navigation systems or extra screens are being dropped in order to stretch the supply of chips further.

In electronics, trade prices for computer memory have risen around 30% since the start of 2020, pushing up costs for items such as laptops and printers. HP has raised consumer PC prices by 8% and printers by more than 20% in a year. Prices for TVs, smartphones and home appliances look set to increase too. The chip shortage also has governments worried.

Why are governments worried?

Chips are now such a crucial component in many strategic technologies – from defence systems to cybersecurity to renewable energy – that their manufacture has become a big geopolitical issue: policymakers say that “chips are the new oil”. They were invented in the US, and much of the cutting-edge design still takes place there, but around 80% of production now happens in Asia because costs are lower: mostly in Taiwan, South Korea and China.

The world’s biggest producer by volume is TSMC in Taiwan. Intel, based in California, is the biggest by revenue. Along with South Korea’s Samsung, these companies dominate high-end, specialised chips. But China is positioned to become the largest producer by 2030: its latest five-year plan sets the goal of meeting 70% of its semiconductor needs by 2025. Europe accounts for less than 10% of global chip production.

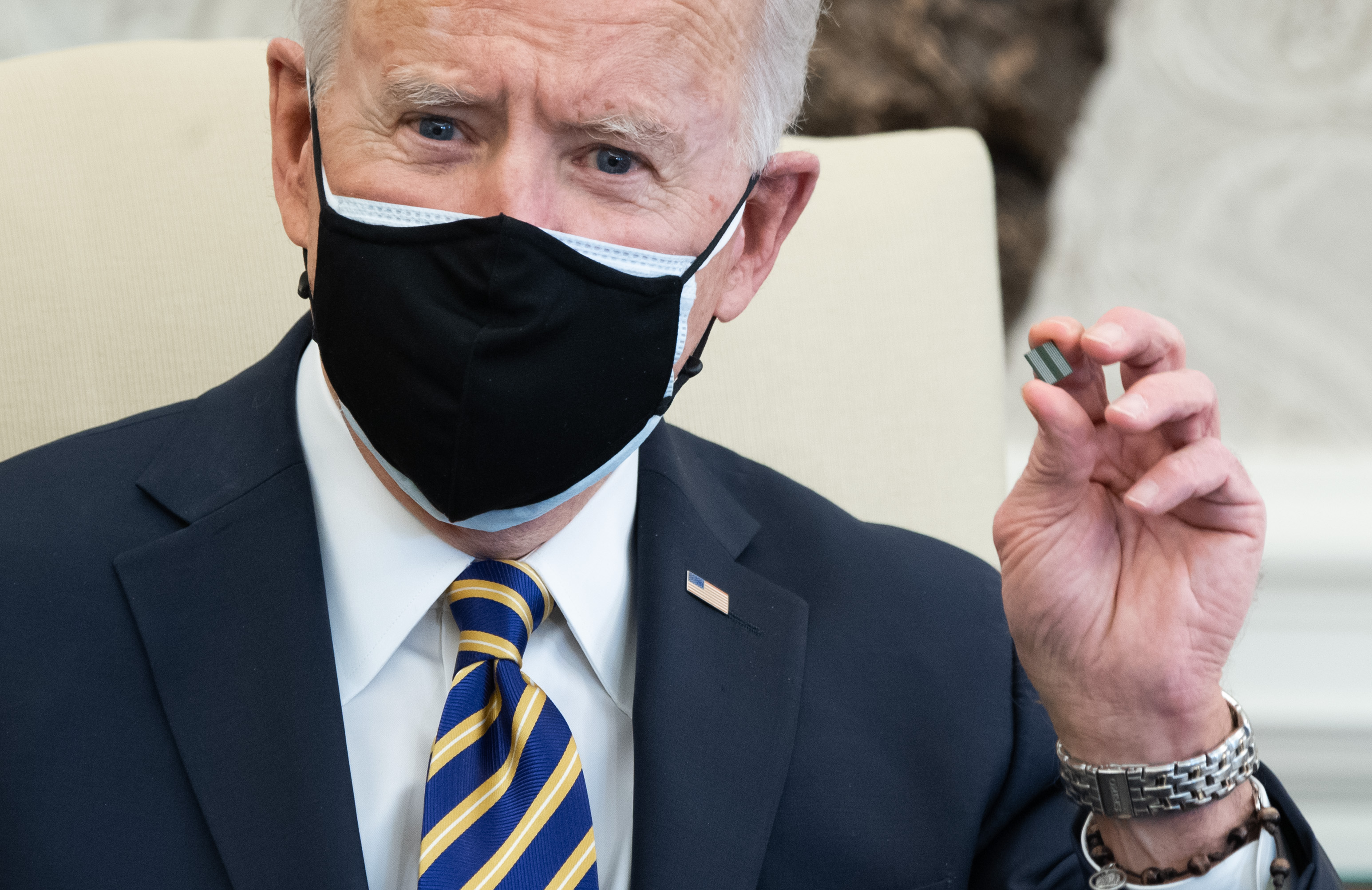

What are governments doing about it?

Last month, the US Senate passed the Innovation and Competition Act, a $250bn bill designed to boost US semiconductor production, along with scientific research and other strategic technologies.

In March, the European Commission set out an ambitious plan to grow its share of the global semiconductor market to 20% by 2030, and committed $160bn of its Covid recovery fund to tech projects. The UK has long had a strong presence in the design side of the industry, but few producers; Newport Wafer Fab, the UK’s largest chip producer, has been acquired by Nexperia, a Chinese-owned company.

How long will the shortage last?

There is no end in sight. Intel’s chief executive, Pat Gelsinger, said that he thinks it could be two years before production is able to ramp up. “The shortage will probably continue for a few years,” said Michael Dell, chief executive of Dell Technologies, earlier in the year. The likes of TSMC, Samsung and Intel are all investing heavily.

But “even if chip factories are built all over the world, it takes time”, says Dell. Many companies are examining their supply chains: Tesla is considering buyingachip plant outright. High-tech industries will probably recover first, towards the end of this year. Cars and home appliances, which use cheaper, older chips will take longer: they are not so profitable for manufacturers, so there is not the impetus for them to invest. Product delays and parts shortages will continue for some time.

The triumph of the microchip

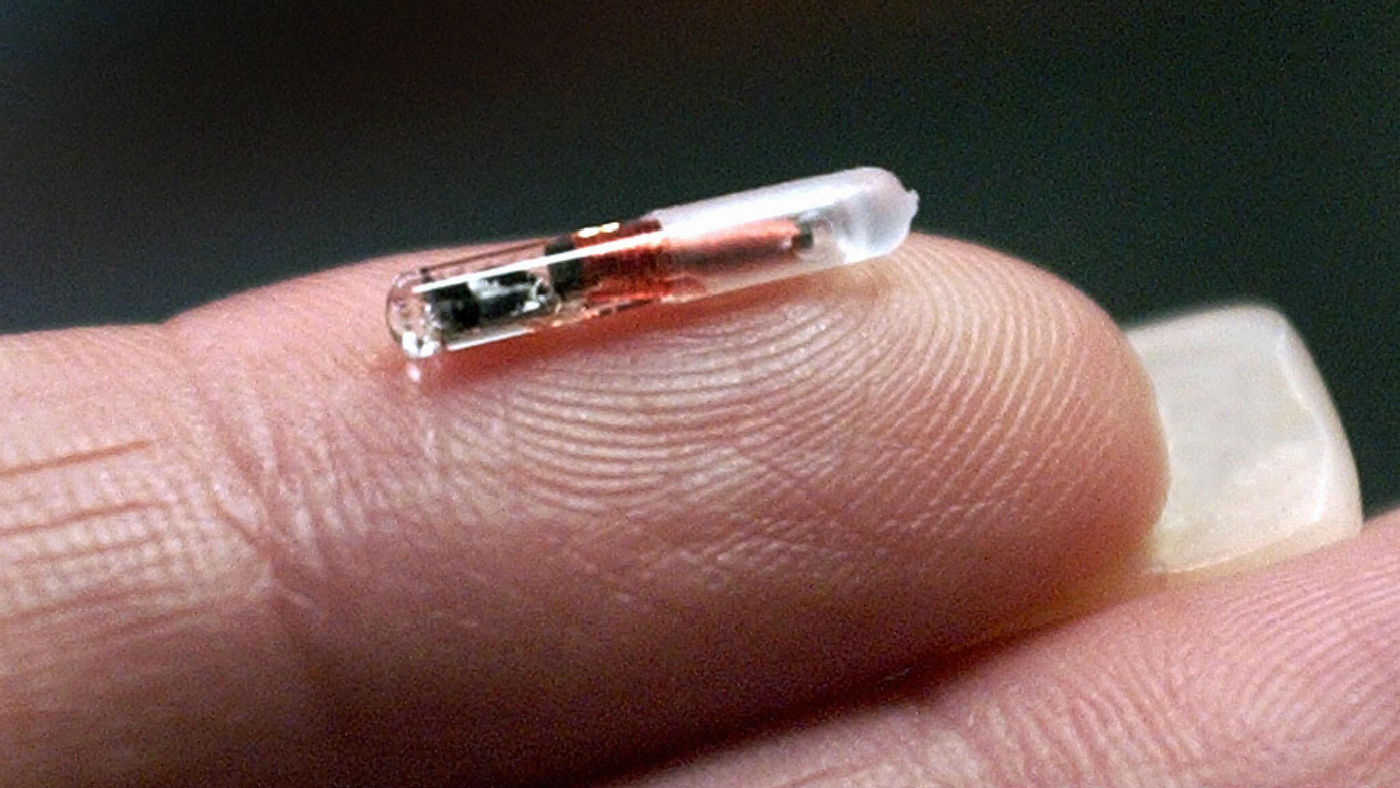

A microchip is a collection of anywhere from a few hundred to tens of billions of tiny circuits on a small wafer of silicon. Silicon is a semiconductor – it can either conduct electricity or contain it. On a chip, silicon transistors are miniature switches that can be turned on and off by electronic signals. Computers run using binary code. Transistors reflect this: the digits 1 and 0 used in binary represent the on and off states of a transistor. Essentially, the chip’s job is to shuttle electrons around in a way prescribed by computer code. All the data on computers – numbers, pictures, music, images – is stored and processed in this way.

The invention of this kind of transistor, at Bell Labs in New Jersey in 1947, and its increasing miniaturisation is the backbone of modern electronics. Moore’s Law, coined by the chip pioneer Gordon Moore, states that the number of transistors on a chip doubles about every two years, making computers ever more powerful.

Today’s advanced chips are dizzyingly complex: lasers imprint circuits just 12 nanometres wide, the length a fingernail grows in 12 seconds. Transistors are thought to be the most manufactured items in world history. The number of microchips sold globally in April reached a record of nearly 100 billion.

The Week Unwrapped: Fashion for rent, a chip shortage and euthanasia

You can subscribe to The Week Unwrapped on the Global Player, Apple podcasts, SoundCloud or wherever you get you get your podcasts.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

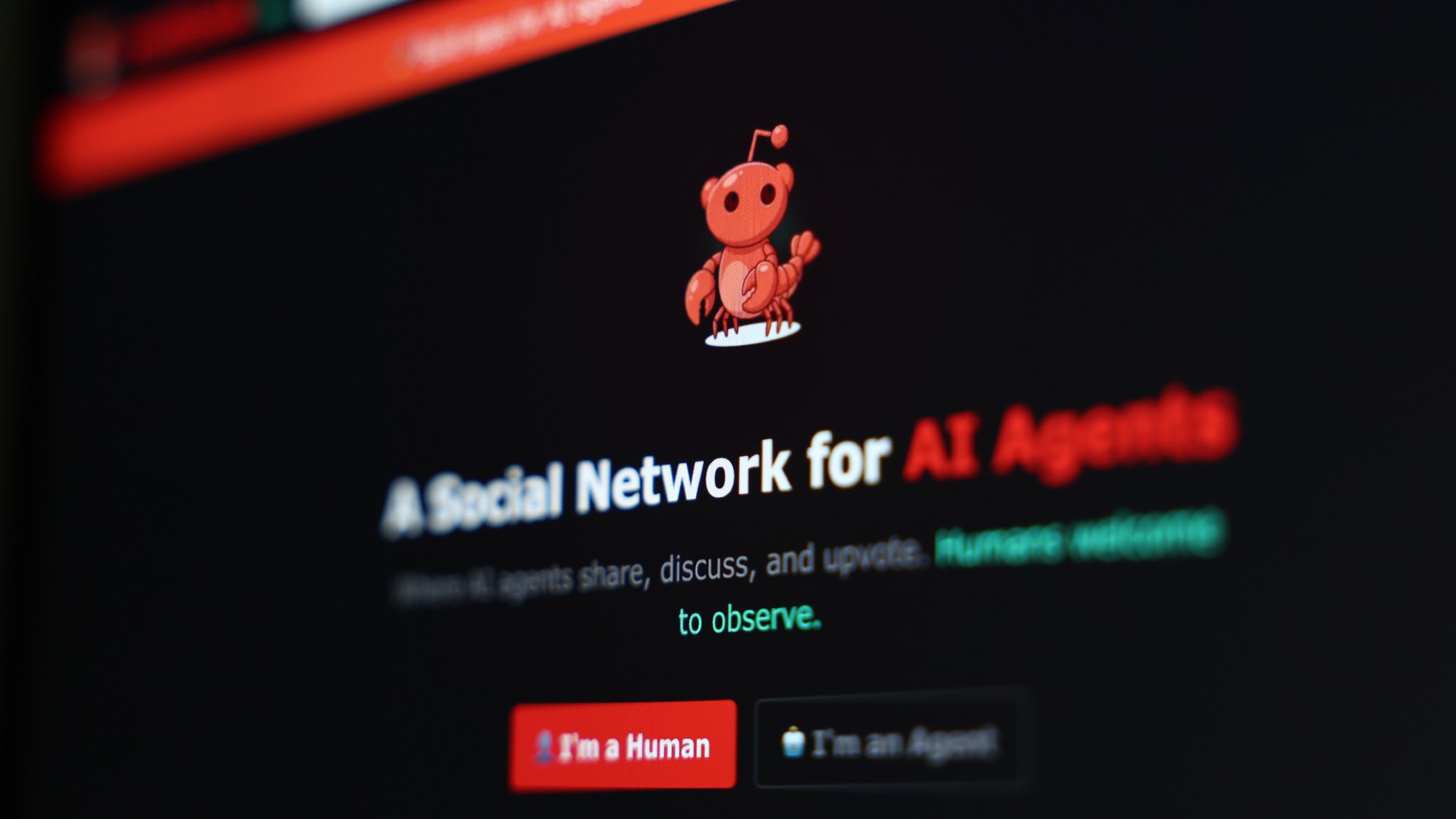

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg

-

Silicon Valley: Worker activism makes a comeback

Silicon Valley: Worker activism makes a comebackFeature The ICE shootings in Minneapolis horrified big tech workers

-

AI: Dr. ChatGPT will see you now

AI: Dr. ChatGPT will see you nowFeature AI can take notes—and give advice

-

Metaverse: Zuckerberg quits his virtual obsession

Metaverse: Zuckerberg quits his virtual obsessionFeature The tech mogul’s vision for virtual worlds inhabited by millions of users was clearly a flop

-

The robot revolution

The robot revolutionFeature Advances in tech and AI are producing android machine workers. What will that mean for humans?

-

Texts from a scammer

Texts from a scammerFeature If you get a puzzling text message from a stranger, you may be the target of ‘pig butchering.’

-

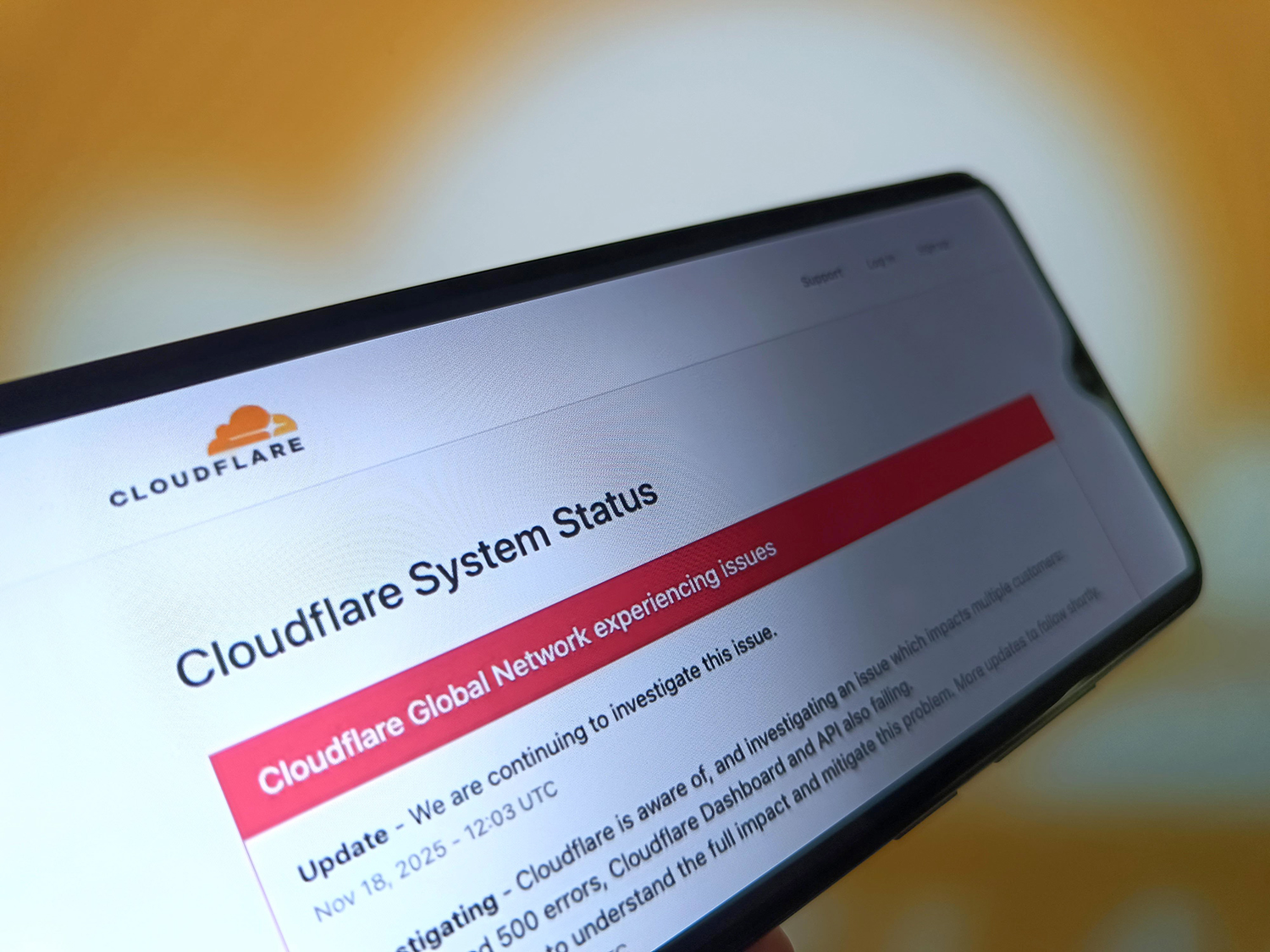

Blackouts: Why the internet keeps breaking

Blackouts: Why the internet keeps breakingfeature Cloudflare was the latest in a string of outages