Should Prince Philip’s will be kept secret?

Controversial practice in ‘national interest’ despite claims it enables Royal Family to hide assets

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The controversy over the decision to keep Prince Philip’s will secret from the public for nearly a century has taken another turn after The Guardian claimed the judge who made the ruling acted unlawfully.

Last September, Sir Andrew McFarlane, the president of the family division of the High Court, ordered Prince Philip’s will be sealed for 90 years. It followed a secret hearing in which he approved a confidential application from lawyers representing the Royal Family.

Now The Guardian has brought a case claiming McFarlane acted unlawfully by failing to notify the media about the hearing.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Are royal wills normally kept secret?

“Royal wills have a long history of privacy, dating back to 1822 when the court ruled in respect of King George III’s will that the sovereign’s will does not need a grant of probate,” said Stewarts, a UK-based litigation-only law firm. “The effect of this is that it is not made public in the usual way.”

Since 1911 High Court judges have approved the closure of the wills of 33 members of the Royal Family “after similarly secret court hearings and applications from the Windsors’ lawyers”, reported The Guardian. It added that the judiciary has never refused such a request.

“It was only in 1987 that the practice was given some legal authority,” said the Evening Standard, citing the Non-Contentious Probate Rules that said a will “shall not be open to inspection if, in the opinion of a registrar, such inspection would be undesirable or otherwise inappropriate”.

“In theory the rules allow for anyone to apply to the President of the High Court Family Division to seal up their will, although it is believed that only the Royal Family has made use of the provision,” said the paper.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The practice has been tested, said Stewarts, most notably in 2007 when someone claiming to be an illegitimate son of Princess Margaret requested the princess’s and the Queen Mother’s wills being unsealed. “He lost, but the court took the opportunity to make clear there is a difference between the rights of the general public to inspect a will and those of an individual asserting a genuine private interest in the will,” said the firm.

“An exception to this was Princess Diana, whose final will and testament is in the public domain and viewable on CNN,” said Business Insider.

What are the arguments for keeping royal wills secret?

While the general rule is that wills in the UK are open to inspection by the public after being admitted to probate, the sole exception is if the court agrees that it would be “undesirable or otherwise inappropriate” to publish it, explained Stewarts. This is what happened in the case of Prince Philip.

In his ruling to seal Prince Philip’s will last year, McFarlane said the special procedure was needed “to enhance the protection afforded to the private lives of this unique group of individuals, in order to protect the dignity and standing of the public role of the sovereign and other close members of her family”.

Lawyers representing the Royal Family in past cases have argued the primary reason and purpose of sealing royal wills is the public interest in protecting the privacy and private affairs of the Royal Family and sovereign and, by extension, to protect the national interest.

And against?

The Royal Family has long been accused of sealing wills to conceal their financial manoeuvrings and information about private and publicly owned properties. Critics argue that as public figures who receive taxpayers’ money their wills, like those of ordinary citizens, should be open to public inspection.

In 2012, the Queen found herself at the “centre of a constitutional row with the revelation that a ‘plainly unlawful’ agreement was struck in an apparent attempt to protect the secrecy of Royal wills”, reported the Standard.

More recently, an investigation by The Guardian claimed that generations of the Royal Family had concealed details of assets worth more than £180m by securing a special carve-out from the law.

“The sealing of the wills has enabled the Windsors to avoid the public seeing what kinds of assets – such as property, jewels and cash – have been accumulated by members of the royal family and how these were then distributed to, for example, relatives, friends or staff,” said the paper.

The argument for using what the Daily Mail called “obscure legal procedure” to seal royal wills in the national interest came under further scrutiny after it was revealed that the convention “thought to be only used for senior members, is actually far more widespread and used for distant relatives”, added the paper.

“It does slightly make a mockery of the whole process that this should be for more senior royals,” said David McClure, a royal finance expert and author of the book The Queen’s True Worth.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Captain Tom: a tarnished legacy

Captain Tom: a tarnished legacyTalking Point Misuse of foundation funds threatens to make the Moore family a disgrace

-

Assisted dying: will the law change?

Assisted dying: will the law change?Talking Point Historic legislation likely to pass but critics warn it must include safeguards against abuse

-

Smoking ban: the return of the nanny state?

Smoking ban: the return of the nanny state?Talking Point Starmer's plan to revive Sunak-era war on tobacco has struck an unsettling chord even with some non-smokers

-

When does adulthood begin?

When does adulthood begin?Talking Point From 16-year-old voters to lifetime bans on smoking, young people are living through a transition in views on political, social and emotional maturity

-

Abortion law reform: a question of safety?

Abortion law reform: a question of safety?Talking Point Jailing of woman who took abortion pills after legal limit leads to calls to scrap ‘archaic’ 1861 legislation

-

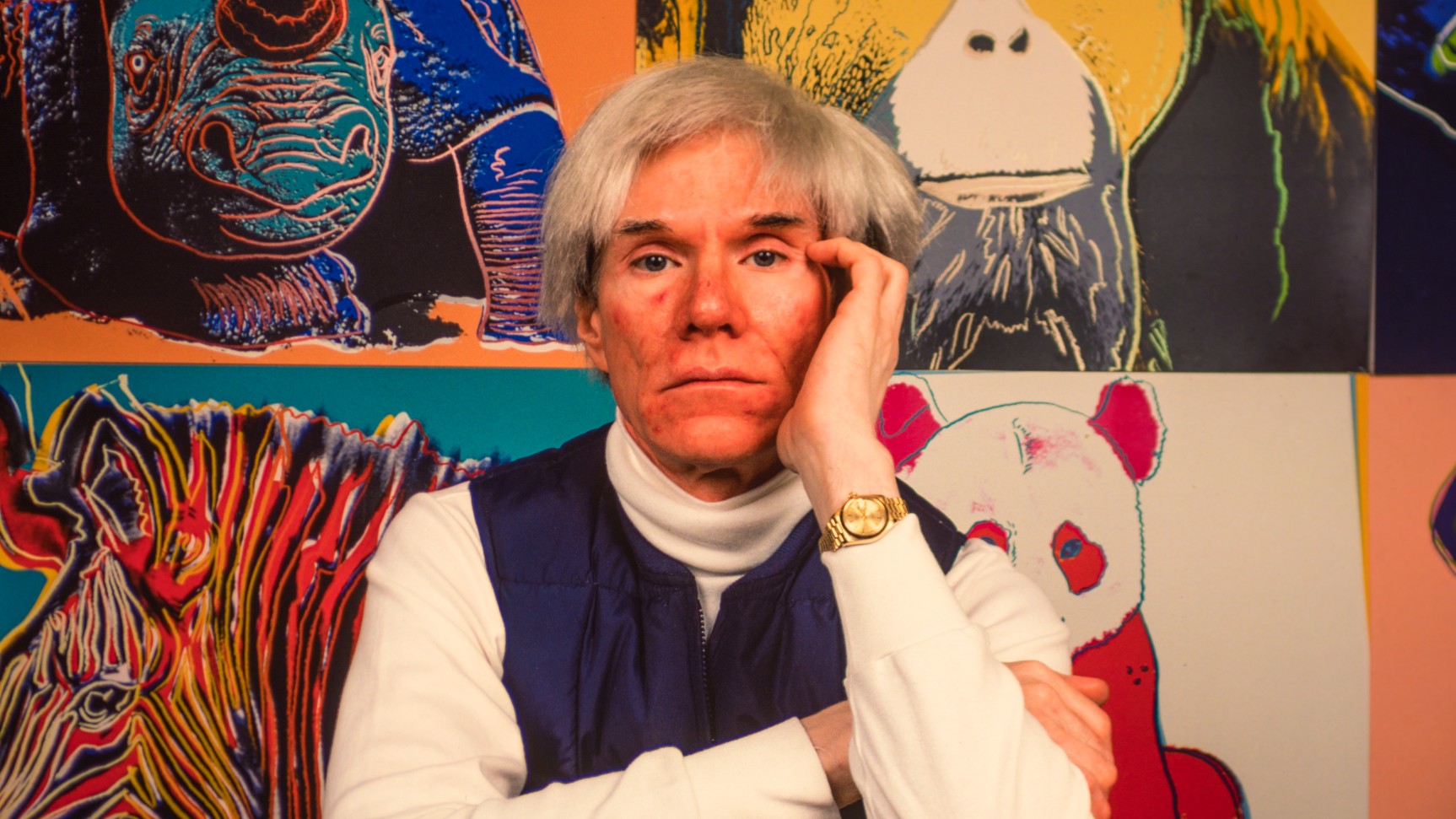

Andy Warhol, Prince and a question of copyright

Andy Warhol, Prince and a question of copyrightTalking Point Supreme Court ruling that sent shockwaves through art world could have huge implications for AI image generation

-

Disaster trolls and conspiracy theories: is legislation the answer?

Disaster trolls and conspiracy theories: is legislation the answer?Talking Point Two Manchester Arena bombing victims are taking landmark legal action against conspiracy theorist Richard D. Hall

-

Menopause: a matter for the law?

Menopause: a matter for the law?Talking Point The Government has decided against making menopause a ‘protected characteristic’ under the Equality Act