The latest nuclear fusion breakthrough explained

Major ‘milestone’ brings quest for infinite power with zero carbon emissions one step closer

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

US government scientists have reportedly made a major breakthrough in the race to develop practical nuclear fusion – the process that promises “limitless, zero-carbon power”.

The Financial Times reported that a successful experiment at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California has for the first time produced a net energy gain in a “fusion reaction” – which is what powers the Sun.

This “milestone” is a major step to help “prove the process could provide a reliable, abundant alternative to fossil fuels and conventional nuclear energy”, said the paper, citing three people with knowledge of the preliminary results.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The US Department of Energy has so far declined to comment but said “a major scientific breakthrough” would be announced at the laboratory on Tuesday.

What is nuclear fusion?

Nuclear fusion is “a way of generating power that, in the broadest brush terms, could potentially provide us with an infinite amount of electricity with zero carbon emissions”, Alok Jha, science and technology correspondent at The Economist, told The Week Unwrapped podcast.

It works by fusing two or more atoms into one larger one, a process that unleashes a colossal amount of energy as heat.

Unlike nuclear fission, which currently powers nuclear reactors by splitting radioactive elements to release energy, fusion does the opposite, explained Sky News.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Fusion “forces two forms of hydrogen to fuse together releasing around four times more energy by weight of fuel than a nuclear fission reactor and four million times more than burning fossil fuels”, said the broadcaster.

Why is it important?

Nuclear fusion would offer a way of generating power that could potentially provide an infinite amount of electricity with zero carbon emissions. “There’s no silver bullet to the climate crisis,” said CNN, “but nuclear fusion may be the closest thing to it.”

Under a fusion reaction, a “small cup of the hydrogen fuel could theoretically power a house for hundreds of years”, said the FT.

It would also be a much safer process than alternative power generation methods. Nuclear fission currently creates waste that can remain radioactive – and therefore potentially dangerous – for tens of thousands of years. After Japan’s Fukushima disaster in 2011, radioactive material leaked into the atmosphere and the Pacific Ocean.

In contrast, operating the power plants of the future with fusion would produce only very small amounts of short-lived radioactive waste.

It is the “holy grail” of clean energy, congressman Don Beyer said earlier this year at the launch of a new White House fusion power strategy, adding: “Fusion has the potential to lift more citizens of the world out of poverty than anything since the invention of fire.”

With the world wrestling with sky-high energy prices and the need to rapidly move away from burning fossil fuels to halt global warming, “the technology’s potential is hard to ignore”, said the FT, even though “many scientists believe fusion power stations are still decades away”.

When could it be used?

There’s “huge uncertainty” about this, wrote the BBC’s environment analyst Roger Harrabin, but it won’t be any time soon.

One estimate suggests “maybe 20 years”, he said, but even then fusion would “need to scale up, which would mean a delay of perhaps another few decades”.

Therefore, it probably won’t be until the middle of the century that this form of power becomes at all commonplace. The European Fusion Development Agreement has established a goal of bringing fusion electricity to the grid by 2050, said World Nuclear News.

The design for fusion was first proposed by Russian scientists in 1950, and the process has become so protracted that a joke in nuclear fusion circles states that a working reactor has been 20 years away ever since then.

What about the latest breakthrough?

Scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California are believed to have produced a net energy gain in a fusion reaction for the first time.

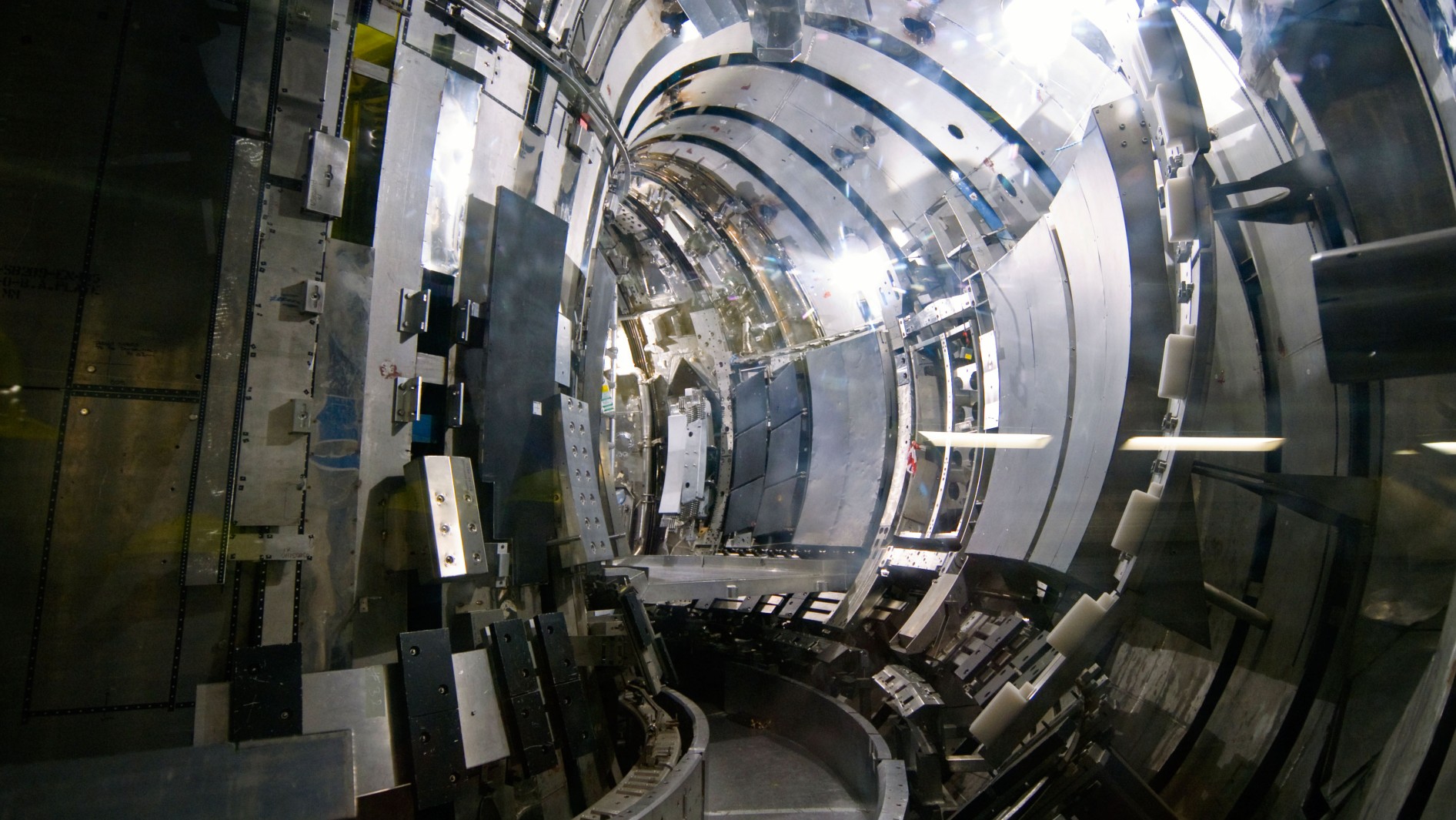

The lab uses a process called inertial confinement fusion that involves bombarding a tiny pellet of hydrogen plasma with the world’s biggest laser. Data from the experiment is still be analysed, said the FT, but the reaction produced about 2.5 megajoules of energy, which was about 120% of the 2.1 megajoules of energy in the lasers.

“If this is confirmed, we are witnessing a moment of history,” said Dr Arthur Turrell, a plasma physicist, told the FT. “Scientists have struggled to show that fusion can release more energy than is put in since the 1950s, and the researchers at Lawrence Livermore seem to have finally and absolutely smashed this decades-old goal.”

Earlier this year scientists at an Oxfordshire lab recreated the way the Sun works to make 59 megajoules of energy – more than double the amount achieved in similar tests back in 1997.

“This is not a massive energy output,” noted the BBC in February – “only enough to boil about 60 kettles’ worth of water”. However, scientists described the results as a significant moment in the quest for clean and reliable power.

The “landmark results” have “taken us a huge step closer to conquering one of the biggest scientific and engineering challenges of them all”, said Professor Ian Chapman, chief executive of the UK Atomic Energy Agency, which co-funds and operates JET.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles

-

Iran at the nuclear crossroads

Iran at the nuclear crossroadsThe Explainer Officials 'openly threatening' to build nuclear bomb, as watchdog finds large increase in enriched uranium stockpile

-

How would we know if World War Three had started?

How would we know if World War Three had started?In depth Most of us probably won’t realise that we are in a global conflict – at first

-

How likely is an accidental nuclear incident?

How likely is an accidental nuclear incident?The Explainer Artificial intelligence, secret enemy tests or false alarms could trigger inadvertent launch or detonation

-

Is Russia planning to blow up the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant?

Is Russia planning to blow up the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant?Today's Big Question Ukraine warns of tactical sabotage that could cause radioactive disaster and force Kyiv into peace talks

-

Which countries spend the most on their military?

Which countries spend the most on their military?feature Defence budgets hit record high as many nations react to war in Ukraine and tensions around China and Taiwan

-

Europe's largest power plant at risk of nuclear accident, Russian officials say

Europe's largest power plant at risk of nuclear accident, Russian officials saySpeed Read

-

Russia will allow UN inspectors at Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant

Russia will allow UN inspectors at Zaporizhzhia nuclear plantSpeed Read