Deep-sea mining: can it help solve our climate problems?

Environmentalists claim mineral extraction could destroy ecosystems, while mining companies argue for its green potential

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A growing controversy is swirling around deep-sea mining, which aims to extract valuable minerals from the ocean floor.

In July, the UN-affiliated International Seabed Authority (ISA) will start considering companies’ bids to mine the world’s seabeds, despite last week failing to agree on regulations.

Earlier this week, an investigation by conservationists, published by wildlife charity Fauna & Flora, argued that seabed mining could cause “extensive and irreversible damage” to the planet.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The July deadline “doesn’t necessarily mean mining is set to begin any time soon”, said Bloomberg. Given the absence of regulations, as well as disagreement among the ISA’s 167 member nations over the practice, “there are doubts about whether licences will be issued and under what conditions.”

But the failure to establish a regulatory framework “means that whatever happens next will take the ISA into unchartered territory”.

So what’s happened?

People started “dreaming of mining the deep seabed” 50 years ago, said New Scientist. “Since then, those dreams have turned into a dystopian nightmare as scientists have found diverse, interconnected ecosystems at the bottom of the ocean”, the magazine added.

In 2021, the Pacific island state Nauru turbocharged the debate by announcing that its seabed mining company intended to apply for a permit. That triggered a legal provision which gave the ISA two years to approve Nauru’s mine. That time is nearly up.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the same year, marine and science policy experts all over the world called for a moratorium on the practice, with more than 700 signatories saying that seabed mining would result in “irreversible” loss of biodiversity and ecosystems.

In September 2021, the International Union for Conservation of Nature voted to support a temporary ban on deep-sea mining until the risks were properly understood.

Who wants to do it?

A 2019 Greenpeace investigation found that the ISA had issued a total of 29 exploration licences, to countries including the UK, China, Russia, France, Belgium, India, Germany and Japan, which are sponsoring corporate contractors.

The licences apply to areas of the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans and cover a total of 500,000 square miles – “five times bigger than the UK” – reported The Guardian.

It also found that the British government held more licences than any state apart from China, and claimed that they were “riddled with inaccuracies”.

As of January 2023, the ISA had entered into 31 contracts with 21 contractors; 19 of those apply to the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, a vast plain in the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii.

Can it help us?

The minerals in the rocks, such as cobalt, nickel and manganese, are vital for green technologies like solar panels and wind turbines, as well as mobile phones. Supplies are running low, while demand is set to rise as efforts to replace carbon intensify.

“These metallic morsels could therefore help humanity save itself from the ravages of global warming, argue mining companies who say their extraction should be rated an international priority,” said The Guardian. “By dredging up nodules from the deep we can slow the scorching of our planet’s ravaged surface.”

Mining companies argue that extracting the minerals from the seabed could help meet demand while factories on land are held up by permit delays and local nimbyism. They also say that drilling for reserves on land could be more damaging to the planet, although do not promise that deep-sea mining would reduce on-shore extraction.

In 2013, then-PM David Cameron promised that deep-sea mining would generate £40bn for the UK over the next 30 years. Greenpeace said it was unclear how this figure had been reached.

Hans Olav Hide, the new Norwegian owner of UK Seabed Resources, said that deep-sea mining could help make the UK and EU competitive “in the face of China’s dominance of battery metal supply chains”, according to the Financial Times (FT). The mineral race and global energy insecurity has been exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and worsening relations with China.

Are there risks?

By dredging the ocean floor for the mineral-rich nuggets, “delicate, long-living denizens of the sea…would be obliterated”, said The Guardian.

Deep-sea mining could also exacerbate the climate crisis, environmentalists argue. “The seabed stores the world’s largest quantity of carbon,” said the FT. If sediment starts to rise, the carbon balance could be upset, increasing pollution and toxic metals in the food chain.

Most experts agree that we don’t yet have enough information on the risks, given that we know so little about the deep-ocean ecosystems.

Even from an investment perspective, deep-sea mining is muddy waters.

Nick Popovic, co-head of copper and zinc trading at Glencore, told the FT Commodity summit in March: “... It’s so early in the game that without any meaningful examples, I would personally struggle to assess it.”

“What we do know,” said the FT, “is that studies indicate that we cannot extract minerals from the seabed without incurring a net biodiversity loss.”

It is a highly polarised dispute, said The Guardian. “For better or worse, these mineral spheres are going to play a critical role in determining our future – either by extricating us from our current ecological woes or by triggering even more calamitous outcomes.”

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric car

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric carThe Week Recommends The family-friendly vehicle has ‘plush seats’ and generous space

-

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ book

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ bookThe Week Recommends Gabriel Sherman examines Rupert Murdoch’s ‘war of succession’ over his media empire

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

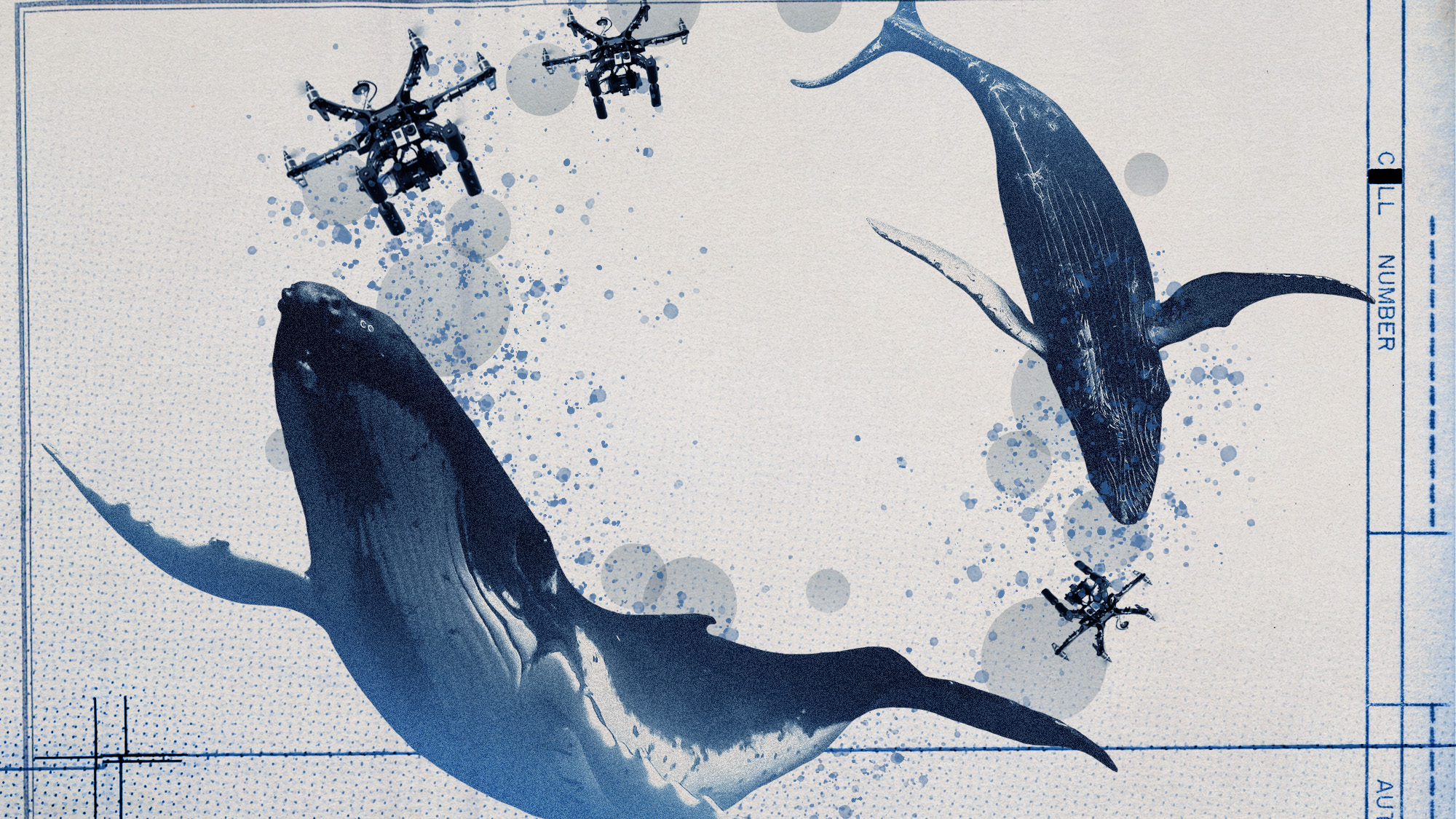

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures