The Chinese Communist Party turns 100: how the world’s most powerful political party began

The CCP’s rule is the third longest of any political party in history

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1911 the Xinhai Revolution, a democratic revolt, ended 2,000 years of Chinese imperial rule, overthrowing the Qing dynasty and giving way to the Republic of China.

The old order disintegrated, but the new republic was weak: much of the nation was ruled by warlords, and much of its economy controlled by foreign powers. Inspired by the 1917 Russian revolution, a group of radicals – including a young teacher named Mao Zedong – established the Chinese Communist Party.

The timing of its founding is unclear – Mao later chose 1 July 1921 when he couldn’t remember the exact date – but in July, around a dozen activists and two agents from Russia’s Comintern (dedicated to the global expansion of communism) met in the French concession in Shanghai, and established the new party.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did the CCP evolve?

Its history can be divided into four main sections. First came nearly 30 years of revolution, during which the Communists established a mass following among peasants and workers, fought a long civil war with their nationalist rivals, the Kuomintang, and narrowly escaped destruction during the legendary 6,000-mile “Long March” to northwest China in 1934; in 1949, the CCP finally defeated the nationalists to establish the People’s Republic of China.

The second period was Mao’s rule, during which Chinese society was radically and brutally reshaped. The Great Leap Forward, from 1958, forced peasants into communal farms and led to up to 45 million deaths from famine; while in the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s, at least 1.5 million people were killed in an attempt to purify the nation ideologically.

After Mao’s death in 1976 came the years of economic and political liberalisation under Deng Xiaoping and his successors. Finally, in 2012 Xi Jinping’s rule began – a period of growing wealth but also of growing authoritarianism at home, and assertiveness abroad.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How successful has the party been?

“China’s Communists are the world’s most successful authoritarians,” as The Economist puts it. The CCP has ruled for 72 years and has transformed Chinese society, albeit at a vast human cost. It united China and drove out foreign powers after the so-called “century of humiliation” from 1839 to 1949. It has survived the demise of Russian and European communism. Its rule is the third longest of any political party in history – after the Workers’ Party of Korea in North Korea, and the Soviet Communist Party (which it will soon surpass).

In the past 50 years, it has directed the biggest and longest economic boom in history, raising 800 million people out of poverty. In 1980, Chinese annual GDP per capita was $195; today it exceeds $10,000.

How has it retained power?

With a mixture of ruthless control and ideological agility. China’s constitution gives the CCP a monopoly on power: leadership is entrusted to “the Communist Party of China and the guidance of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong thought”. “Sabotage” of the system is “prohibited” and punished. There are eight other political parties, but they are merely symbolic. The armed forces, the People’s Liberation Army, are commanded by the party, not the state.

The CCP censors all mass media. But it has also shown great flexibility – notably in the form of Deng Xiaoping’s adoption of “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. Theoretically a form of Marxism-Leninism, this is in fact a one-party political system combined with capitalist economics: Deng rolled back state ownership, ended price controls, de-collectivised agriculture, and opened up China to foreign investors.

How is the party structured?

The CCP has 92 million members. Although its membership is second in size only to India’s BJP, it is relatively exclusive: this represents only 7% of Chinese adults, and joining is a complex, gruelling process.

Even within this, the party system is designed to concentrate power in the hands of a very small number of people. The National Party Congress selects its own 2,300 delegates from the membership, and it convenes every five years to elect a Central Committee of 376 members.

The real power, however, lies in the three tiers above that: a 25-member Politburo that, in turn, elects a powerful seven-member Standing Committee. Since 2012, this has been led by the General Secretary, Xi Jinping – also president and head of the military.

How do people join the CCP?

The CCP defines itself in Leninist terms as “the vanguard of the working class”, but not any old worker can join it: up to 80% of applicants are rejected. In China, aspirants have to apply in writing with the endorsement of two members. If they pass the first stage, the CCP will conduct detailed background checks.

Once vetted, applicants will attend a three-day course on the ideology of its three great leaders: Mao, Deng and Xi. Only at this stage can they officially apply. If successful, they will swear an oath in front of a party flag, and enter a year-long trial membership.

Joining is often a pragmatic decision: membership is required for good jobs in the civil service and state industries; it gives excellent networking opportunities. Businesspeople were not allowed to join until 2001, but by 2016, almost 70% of private companies in China had a “party cell”. The ratio of members who are workers and farmers has fallen from almost 40% in 2009 to a third in 2019; only 28% are women. And with opportunity comes temptation: since 2012, Xi has launched a major campaign against corrupt officials, which has seen over 100,000 people indicted, including many party chiefs in China’s provincial capitals.

How is Xi’s rule distinctive?

The hallmark of his time in office is a drastic centralisation of power. Xi’s predecessors allowed a measure of mild dissent; Xi has stamped on it. Deviant and corrupt officials have been purged. Not since Mao’s day has society been so closely controlled. Deng’s modest political reforms have been rescinded: Xi scrapped presidential term limits, establishing himself effectively as “emperor for life”.

Xi has his own Mao-like cult of personality. “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” has been enshrined in the constitution: its central plank is that a powerful, unified China can be achieved only if the CCP stays firmly in control.

What will happen in the future?

The party has presented a bargain to the Chinese people: accept our control over daily life, and we will deliver economic growth and improve the lives of millions. It has largely kept its end of the bargain, but this requires a balancing act – liberalising enough to keep growth going, but not so fast that social chaos ensues.

There are certainly tensions: China today is one of the world’s most unequal countries, far more so than most capitalist states: a 2016 Peking University study found that the richest 1% of households held a third of the country’s wealth. However, the CCP remains popular at home and respected abroad. A generation ago it was widely thought that the path to progress lay with democracy. China has provided a powerful alternative.

This article was corrected on July 6 to reflect the CCP's reputation abroad

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

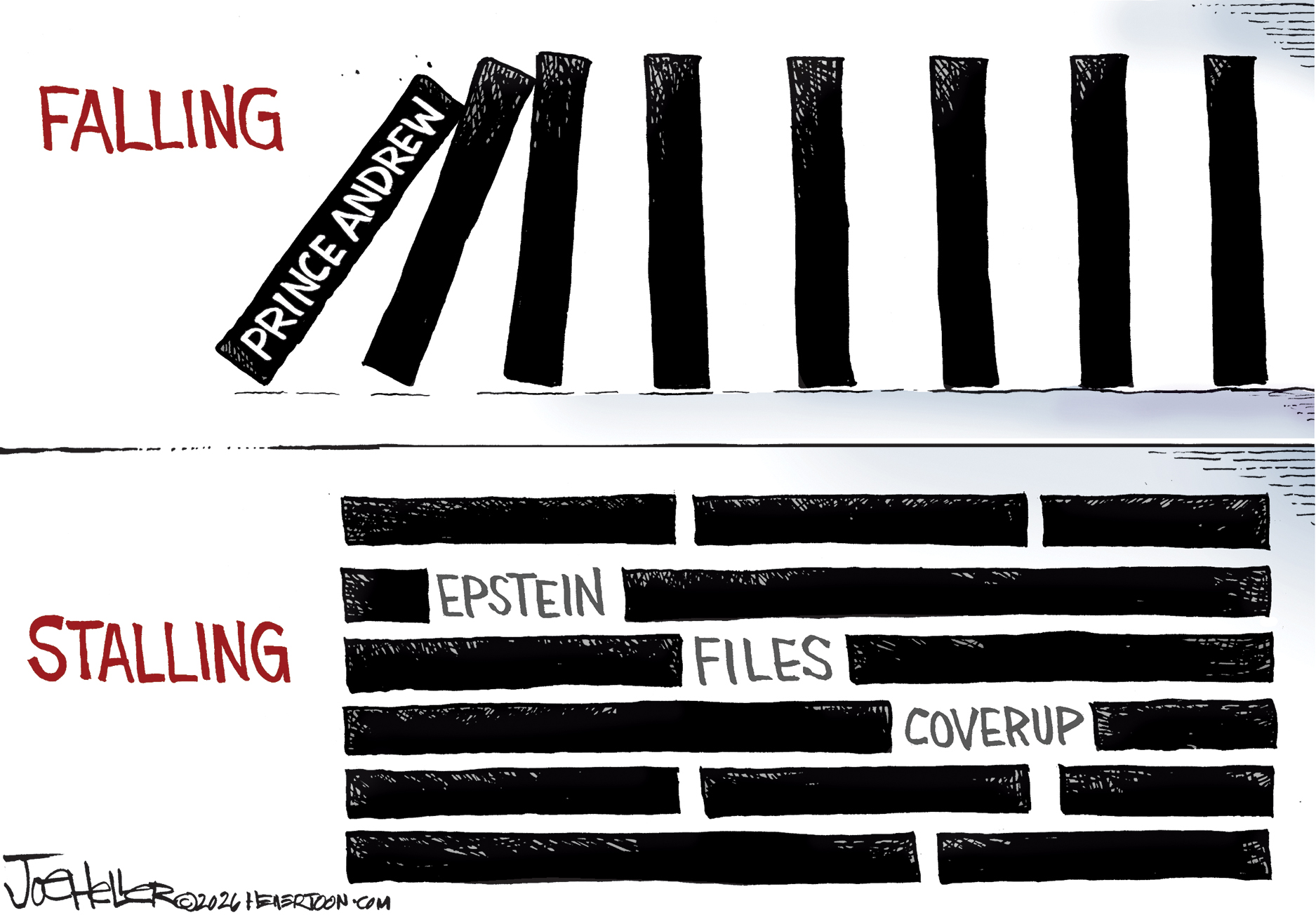

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

The identical twins derailing a French murder trial

The identical twins derailing a French murder trialUnder The Radar Police are unable to tell which suspect’s DNA is on the weapon

-

The mystery Malaysia Airlines of flight MH370

The mystery Malaysia Airlines of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack