Will the left get the last laugh in the NYC mayoral race?

Thanks to ranked-choice voting, progressives could get blown out and still determine the next mayor of New York

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A year after protests against police brutality rocked the city to its core, and three years after left-wing firebrand Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez upset 10-term incumbent and Democratic Caucus Chair Joe Crowley, the progressive tide in New York City shows clear signs of going out.

In the upcoming Democratic primary that will likely select the next mayor, the top three candidates in recent polls — Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, entrepreneur Andrew Yang, and former sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia — are all moderates or centrists of one kind or another, who have avoided or actively run against the litmus-test politics of the progressive wing. In particular, all three have strongly opposed defunding the police. Not only are the moderates topping the polls, they are collectively polling at more than twice the support of the three most progressive candidates, Comptroller Scott Stringer, television commentator and former DeBlasio advisor Maya Wiley, and not-for-profit executive Dianne Morales.

So why could the most progressive voters wind up selecting the next mayor after all?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

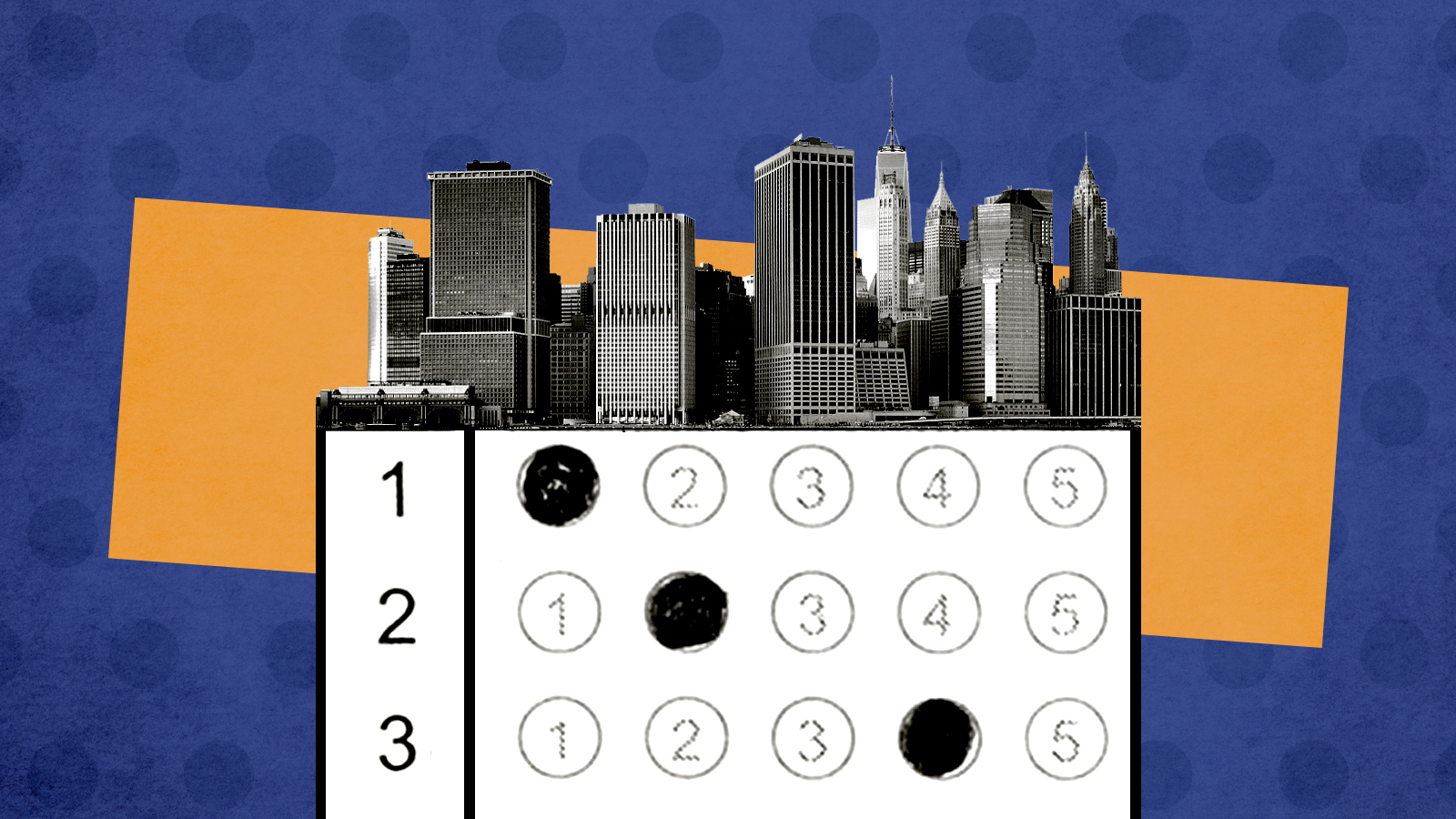

The answer has everything to do with the peculiar dynamics of ranked-choice voting. In NYC's ranked-choice system, voters don't just pick a single candidate, but can rank their top five choices for each office in order. If no candidate finishes with a majority on the first ballot, the ballots for the candidate with the lowest vote total are retabulated based on those voters' second choice. Then the second candidate from the bottom's votes are retabulated, and so forth, until one candidate crosses the 50 percent threshold.

It's supposed to be a system that allows voters to express their full spectrum of views, and to ensure that a consensus candidate is ultimately elected with what looks like majority support. But that's not necessarily how it plays out in reality. In Alaska, for example, a recent poll suggests that ranked-choice voting could deliver the election to a more partisan Republican even though the consensus candidate, moderate GOP Sen. Lisa Murkowski, would beat either the Democrat or her Republican challenger in a head-to-head contest. Why? Because on a first ballot Murkowski would come in third, but a portion of her supporters would prefer another Republican to a Democrat, while the Democrat's supporters would overwhelmingly prefer her. Because the order in which candidates end up on the first and subsequent ballots can determine the outcome, strategic voting can be just as important in ranked-choice contests as in traditional multi-candidate elections.

The result in a ranked-choice system can also be shaped by whether voters actually deploy all of the preferences at their disposal. A voter with strong views about every candidate will be able to express those views with their rankings; a voter who likes their candidate but is ignorant of the others could wind up throwing away their vote on subsequent ballots, either by not ranking anyone beyond the first choice or by choosing their subsequent rankings based on weakly-considered factors. In a complex multi-candidate race, those second and third choices could prove decisive.

That's why I say the progressive vote could still pick the winner. The most left-wing voters who have predominated in the Morales, Wiley, and Stringer campaigns are likely the most ideological voters in the primary, with some of the strongest views about the candidates, positive and negative. How they view the moderates could determine their final fortunes. If they overwhelmingly back one of them on subsequent ballots, that will almost certainly put that candidate over the top. And because totals are recalculated after each round, everyone will know just whose voters made the difference.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Which candidate will that be? Adams has strong support from the city's Black community, particularly in Brooklyn, and has a background as an advocate for police reform from his time in uniform as the co-founder of 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care. But he has also come under heavy fire for being a former Republican, and has run strongly on a law-and-order platform that is anathema to the activist left. Once upon a time, Yang won support from some progressives based on his policy ideas, specifically his signature issue of a universal basic income. But he is widely perceived as unprepared and easily swayed, has been attacked for allying with investor and consultant Bradley Tusk who has worked in the past on Republican and more business-friendly Democratic campaigns, and is widely distrusted in activist circles.

Of the more moderate troika, it's Garcia who looks most likely to benefit from progressive voters, because, while she isn't one of them, she's viewed as an honest candidate who isn't their enemy. Garcia's message on public safety has been very savvy, opposing defunding but calling for a culture change at the NYPD and saying she will hold the police accountable for bringing down crime. She doesn't view the police as the enemy — but she wants them to do their jobs, and face consequences if they don't. Like Yang and Adams, she's supportive of development and of making New York more business-friendly, but she doesn't have their close ties to specific business interests. She has a lot of experience in government, and is enthusiastically supported by the unions she faced across the table as a manager, but owes nobody favors because she's never before run for office. And one of her signature issues — climate resiliency — may well strike a chord with the left as well as mainstream voters. It's notable that she won the endorsement of The New York Daily News, which chose Adams second and pointedly described the election as partly a referendum on the activist left, and also from The New York Times, which didn't indicate a second choice but which praised Stringer's experience and progressive ideas, suggesting he might have gotten their nod were it not for sexual harassment allegations.

Garcia, then, is the kind of consensus candidate that ranked-choice voting is supposed to produce. If she wins, it'll be because progressives strongly preferred her to Adams and Yang. She'll have won their support without having to court them directly, which may limit the influence their views will have in her administration. But she'll also know that she owes them the mayoralty — and so will they. With little political base of her own, the first year of a Garcia administration could well hinge on how she handles the divergent expectations of moderates and progressives.

But Garcia shouldn't be measuring drapes yet, because that isn't the only way ranked-choice voting could play out. Progressives could also put one of their own over the top — at least briefly — if they consistently rank progressives as their top three choices.

Stringer, Wiley, and Morales are all running behind the three leading moderates in current polls. But combined, their vote totals more than the front-runner's. If their voters all choose the other progressives as second and third choices, then it's entirely possible that after several rounds of counting, with only four candidates left, a progressive will be in the top two.

What happens then? We don't know. Do Garcia's voters choose a seasoned pro like Stringer even though he's more left-wing? Or a fellow moderate like Adams despite his baggage? Or another history-making woman like Wiley despite her inexperience? Do Yang's voters choose Garcia, who Yang once promised to hire? Or do they only vote for him, and leave the rest of their ballot blank? Will the bad blood between the Yang and Adams camps translate to their supporters? Or is it something that only matters to political insiders? We have no idea — and there will be no runoff campaign to help define a two-person race, clarifying for voters what that choice signifies. A progressive who placed fourth on the first ballot could wind up winning it all if things break just right — or could wind up losing to a candidate who progressives despise.

Ironically, then, in a race that has skewed decisively against the left, the most ideologically-committed left-wing voters could well determine the outcome — but only if they vote strategically. Ranked-choice voting, which is supposed to let voters choose with their hearts, may require them to use their heads more than ever before.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred