A healthier politics is possible

Must politics be a fight to the death? This week just showed us a better way.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The strange thing about political extremism is that at a certain point it unfolds according to its own logic.

Ask the most radical ideologues and analysts on the right why they have taken to entertaining or concocting arguments justifying an American Caesar or Salazar, and they will tell you it's because the other side is already practicing authoritarianism and actively seeking to impose soft totalitarianism on the country. We're just trying to defend ourselves, they'll say. In such a circumstance, failure to use any and all tactics available would be foolish, like tying your own hands in the midst of a battle to the death with a mortal enemy.

The other side made me do it, in other words.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And of course that other side feels precisely the same way. The right is a massive threat to American democracy, progressives say, so it's long past time to fight dirty, using every possible means to rig the system in favor of the left as the only possible defense against those who are already rigging the system to enhance the power of authoritarian conservatives.

Call it the seduction of political ruthlessness, with self-defense used as a rationale to justify each intensifying round of offensive action against political opponents.

But is this our inevitable fate? Are we condemned to endlessly reiterated cycles of mutual provocation and escalation, each fueled by the ever-intensifying conviction that any political victory for the other side is too dangerous to countenance?

Two recent political developments remind us that it doesn't have to be this way — that even now, another, healthier form of democratic politics is possible.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The first of these developments defies a dynamic that has come to prevail in recent years among Trumpified Republicans. Keen to find and take political advantage on all occasions, they have hit on a completely situational view of principle — which is to say, they treat principles as binding only on their opponents.

So if the Democrats find themselves facing a scandal in which a prominent member of their party is credibly accused of moral impropriety or corruption, Republicans respond to any sign of hesitation to respond harshly by hurling accusations of hypocrisy and bad faith. Yet if a Republican is accused of moral impropriety or corruption, their own response is considerably more latitudinarian. Why? Because turning on a member of one's own political tribe, regardless of his or her alleged transgression, would be an expression of weakness. That's how we ended up with lots of Republicans goading the presidential campaign of Joe Biden about a single, flimsy accusation of sexual assault when the Republican president had been accused of (and was caught on tape confessing to) far worse behavior.

In the land of political extremism, double standards are the coin of the realm.

Yet, interestingly, this is one area where the two parties have not mirrored each other. We've seen this over and over again in recent years, from the rapid and widespread calls for Al Franken to resign his Senate seat in Minnesota after he was accused of sexual harassment to the response of Democrats this week to the damning results of an investigation into New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Calls for Cuomo's resignation began almost immediately after the report stating that the governor sexually harassed 11 women and created a "hostile" work environment for women more generally was announced midday Tuesday. Over the following day, many high-profile Democrats, including President Biden and the Democratic majority in the New York State Assembly, had called for his resignation.

At the moment, Cuomo's fate remains uncertain, but the moral character of the Democratic Party does not. Its leading office holders have demonstrated that the party will take a stand on principle even when doing so harms one of its most prominent members (and not only when the gesture can be used as a bludgeon against the other guys). That points to a real and important difference separating the two parties — and also serves as a salutary reminder of what a less polarized form of politics looks and feels like in action.

We've also seen signs of a better way in the bipartisan infrastructure deal that Biden encouraged and moderate members of both parties have forged in the Senate over the past couple of months. We can debate whether the mix of policies and the size of the spending in the 2,700-page bill (whose passage remains uncertain) is too much, too little, or just right for the country. But the very fact that such a bill was written at all is a hopeful sign that the extremist logic that so often prevails today can be short-circuited, at least sometimes.

That logic insists that politics is about all-or-nothing partisan victory or defeat. If one side wins, the other loses. If one side gets its way, the other suffers, both in terms of partisan advantage and policy preferences. There is no overlap, no common ground or notional common good that can be hashed out and partially achieved through negotiation or compromise. If the other party prevails on anything, we are defeated. Like a civil war waged by other means, politics is zero-sum, with skirmish lines shifting back and forth on an ideological battlefield map. One side pushing forward implies the other pulling back, losing vital territory that must be regained the next time the armies clash.

Much of what happens in our politics these days can be described this way. But that hasn't been the case with the infrastructure deal, which is a very hopeful sign. The center-left White House started out with a proposal, and then a sizeable bloc of moderate Democrats and Republicans set to work, agreeing to what they could, discarding the rest to be taken up in what will probably end up being a far larger and more progressive bill that the Democrats will try to pass through the reconciliation process on a straight party-line vote. What remains is a nearly $1 trillion bill with money for a long list of "hard" infrastructure projects (roads, bridges, rail, etc.) and investments in clean energy and climate-change-related environmental projects.

The left isn't happy, and neither is the right. Yet Congress and the White House have done precisely what they are supposed to be doing, which is to govern the country fairly and responsibly. Which means that they hashed out a rough and ready compromise by giving both sides something of what they want and can live with.

That won't work on everything. But as long as it's successful some of the time, the seemingly inexorable logic of political extremism can be kept in partial check and maybe even placed, now and then, on the defensive.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

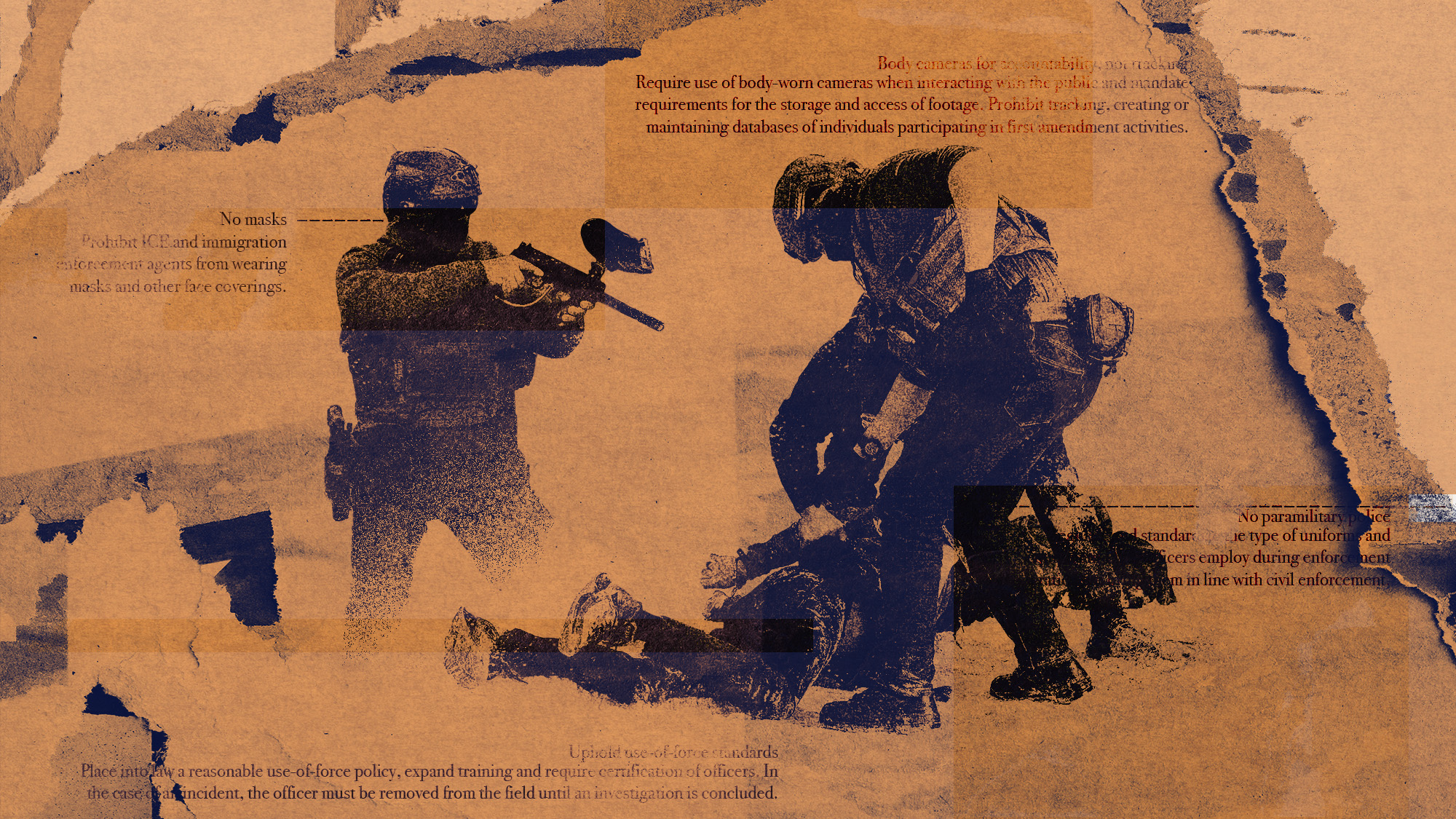

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’