What the fantasy of a new constitution reveals about the left

'Democracy' journal's experiment with constitutional reform goes off the rails

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Solving a problem requires grasping its true character. That can be difficult, especially when those attempting to devise a solution are immersed in the context that produced the problem in the first place.

Thoughts like these came to mind while reading and pondering a stimulating symposium in the Summer 2021 issue of Democracy, the esteemed quarterly journal of progressive ideas edited by Michael Tomasky. The symposium takes the form of a constitutional convention, with more than three-dozen left-leaning legal scholars, led by Sanford Levinson of the University of Texas law school, debating and then drafting a complete alternative constitution. A handful of those invited to participate ended up dissenting from the exercise, and Tomasky also asked a few additional people to provide comment at the end.

Tomasky is right to call the result, in his brief opening remarks to the symposium, "ambitious," "audacious," and "unapologetically progressive." Everyone interested in thinking through the strengths and weaknesses of our current system of government should wrestle with the document's many proposed institutional adjustments. These include abolishing the Electoral College; making the Constitution easier to amend; weakening and democratizing the Senate; embracing a variety of electoral reforms; and reining-in the Supreme Court in various ways (including setting fixed 16-year terms for justices, encouraging compromise and coalition-building by placing an even number of justices on the high court, and limiting its ability to invalidate laws passed by Congress).

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I don't support all or even most of these proposals, but they are fruitfully provocative and very much worth thinking about. What's far less helpful is the document's opening section: a greatly expanded Bill of Rights. That's where the journal's experiment with constitutional reform goes off the rails, moving from a notionally plausible list of proposals for change into a fantasy of progressive triumphalism. Indeed, the very fact that participants in the symposium thought starting their imagined document in this way shows us something deeply dispiriting about the left — namely, its thoroughgoing incapacity to rise above the political fray to grapple with the exigencies of American reality.

In his lengthy essay laying out the problem the symposium is intended to solve, Levinson asserts that the Constitution of 1787 has become nothing less than "a clear and present danger to our national survival." The new constitution proposed in the symposium aims to remove this supposed threat to our existence as a nation.

Levinson's acknowledgment of the political precarity of the present moment makes it all the more surprising that the document's first section — Article 1 — is a list of rights more than three times longer than the Bill of Rights that appears as a kind of addendum to the Constitution of 1787. Political scientist Jeffrey Tulis, author of one of the dissents included in the symposium, is right to object to the placement of the new, more elaborate Bill of Rights immediately after the document's preamble rather than at its conclusion. As Tulis puts it, this foregrounding of rights threatens to be "culturally corrosive" by diminishing "both the intelligent discussion of power and its limits and also the multiple legitimate and democratically contestable ways to secure the common good."

The point demands broader elaboration.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A right is something that ends politics. To declare something a right is to place it beyond democratic deliberation and contestation. This is why our fights about the judiciary are so rancorous — because courts in our system have great power to declare and define rights. To gain control of the courts is to wield the power to rule certain laws and policies in or out of bounds.

This is a second-order power — a kind of metapolitics that determines what's permissible in ordinary politics. It's the power to act as the author and enforcer of the rules of the game that prevail in our public life. Want to outlaw abortion? Or ban semi-automatic weapons? You can try to do either through the political process, but if courts determine that the effort transgresses a fundamental right protected by the Constitution, you're out of luck. In that case, the effort will be blocked — halted in its tracks by the magic words, "You can't do that." Why can't we? Because rights are inviolable. If a political act infringes them, the political act must be stopped.

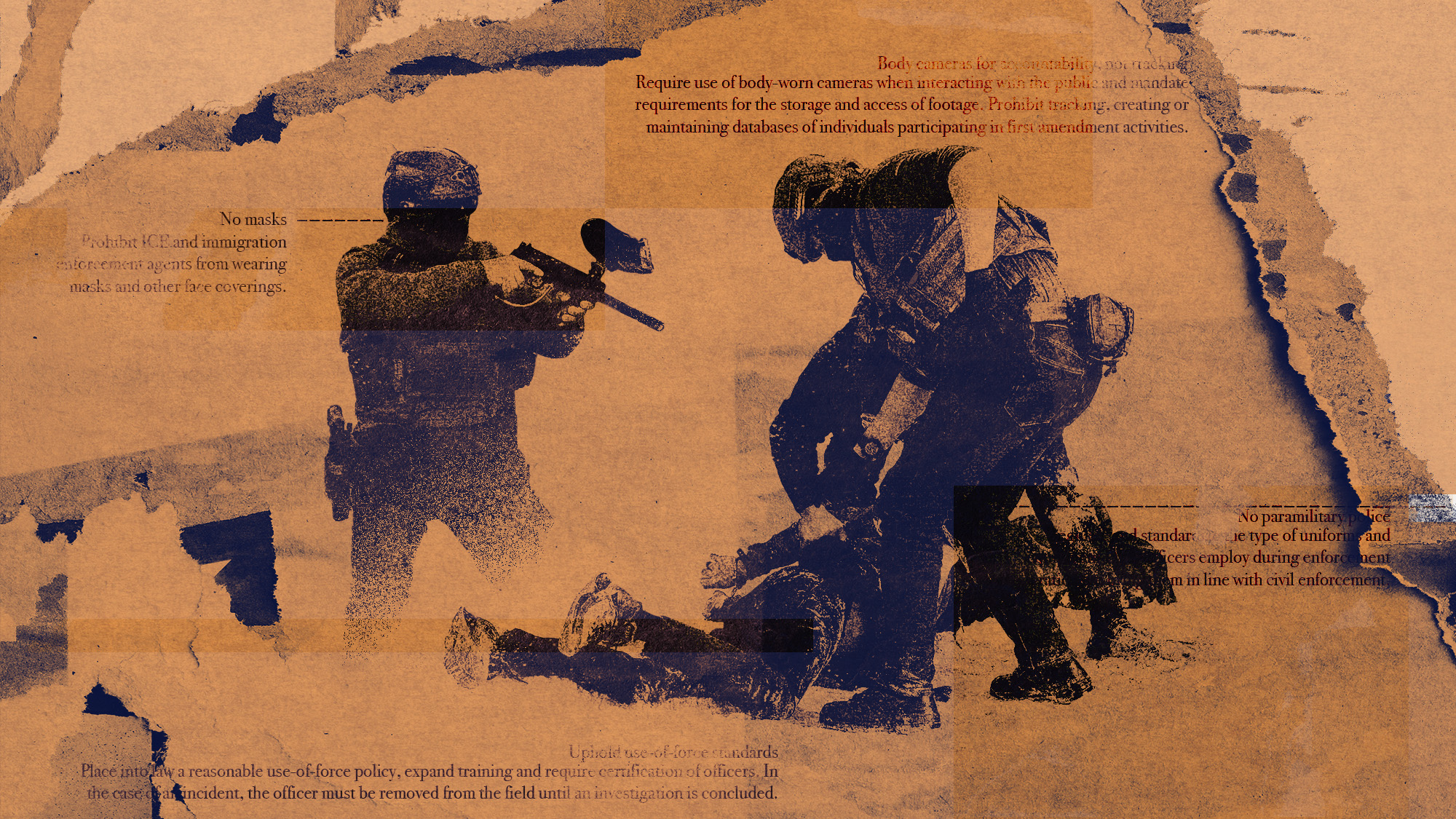

Now consider the rights proclaimed by the progressives involved in the Democracy symposium. Most of the rights contained in our current constitution are found there, including rights to free speech and assembly, religious worship, jury trials, and a ban on unreasonable searches and seizures — along with a good part of 20th-century jurisprudence surrounding criminal procedure.

This last move might prove controversial with some. But it's broadly compatible with the highly formal and limited rights contained in the original Bill of Rights. Those rights were primarily efforts to set minimalistic, foundational rules or preconditions for a free government. Such a government can do lots of things and pass lots of laws, but it can't restrict the freedom of individuals or groups to speak or associate together, or prevent them from worshipping God the way they wish, or search their homes without cause, or throw them in jail without a public trial. Those and a few other basic rights constrain what government can do to individuals and groups. But beyond these few limitations, and those contained in constitutional amendments passed later in American history, the government has the leeway to follow public opinion as measured in democratic elections and act according to the institutional rules laid down earlier in the document.

But the Democracy constitution's Bill of Rights goes much, much further, following the lead of the European Union's Charter of Fundamental Rights (which came into force in 2009) in treating a wide range of substantive policies as rights that must be provided and cannot be infringed — and therefore ruling broad swaths of potential democratic disagreement and disputation out of bounds.

On the negative side, the new constitution eliminates one of the fundamental rights protected by the original Constitution — a right to keep and bear arms.

As for additions, there are many. The new constitution includes of a blanket right to "reproductive freedom," which would presumably enshrine abortion on demand, from conception through birth, in the nation's foundational law. And a total ban on capital punishment. And the declaration of a "right to dignified labor" and to "health, safety, and community," along with "a right to adequate health care, including preventive and reproductive health care." And a "right of the people to clean air and water." And the elevation of anti-discrimination law and affirmative action into explicitly stated constitutional rights.

And the declaration of a "right to work under equitable and safe conditions" and to receive "equal pay for equal work." And the right to a "decent standard of living" backed up by "an annualized income amounting to no less than one-fourth of the annual compensation received by members of Congress." And a "guaranteed freedom from unjustified dismissal." And the declaration that the country shall have "a federal tax structure that is based on progressive taxation" and that Congress shall have a "duty to impose a tax on income, wealth, and estates," with the constitutionally mandated wealth tax levied against anyone possessing "wealth in excess of two-hundred times the compensation of members of Congress" and amounting to "an annual tax of no less than 2 percent of that excess wealth."

The problem with including this long list of extremely specific items in a constitution isn't that the goals are unappealing. I would be quite happy to live in a country with many of these policies, though of course many millions of Americans wouldn't at all. And that's the point — and the core of the problem: By declaring these numerous policies "rights," the authors of the document are attempting to come out on top in a political disagreement by rigging the system so that it systematically delivers progressive outcomes. That isn't how politics works. On the contrary, it's effectively a proposal to end politics — to place a long list of issues on which progressives have strong preferences beyond the bounds of democratic dispute.

The best that can be said for the proposed document's Bill of Rights is that it's merely the opening, maximalist bid in an imagined negotiation with non-progressives. This is how Tomasky describes the rationale behind the whole project, in fact: "let conservatives write their dream constitution, we said, while we write ours." That's fine, I suppose. But doesn't it guarantee that the exercise will merely reproduce the distinctive pathologies of our sharply polarized and dysfunctional political moment? What the symposium has given us is a constitution suitable for a United States inhabited entirely by progressives, which obviously isn't at all the United States that actually exists.

Despite what both Tomasky and Levinson suggest in their introductory statements, the problem confronting America in the 21st-century is not our 18th-century institutions alone. It's the interaction of those institutions with the contingency of contemporary America's deeply polarized public opinion. Tomasky and Levinson may not see this because, like many on the left, they've convinced themselves that the American reality is one in which (in Tomasky's words) "about a third of the American public" use our institutions to "thwart majority will."

But this is a self-congratulatory fantasy. Yes, Joe Biden won a majority of the popular vote in 2020 — 51 percent — but Donald Trump's 47 percent added up to quite a bit more than "about a third of the American public." The same goes for the House, where Democrats won just under 51 percent of total votes cast and Republicans just under 48 percent, and the Senate, where Republicans actually won 49 percent of the total vote and Democrats 47 percent. That is simply not a picture of a country in which a third of the electorate uses anachronistic anti-democratic institutions to impose its will on a sizable progressive majority. It is a picture of a country quite closely and deeply divided about how to govern itself — and with institutions that often succeed but sometimes fall short of translating with perfect precision that dividedness into representation.

We see the same move over and over again in our politics. It was there in Trump's refusal to govern with even the slightest hint of humility after the narrowest of wins in 2016, and in Mitch McConnell's willingness to use every ounce of power he could muster with a narrow Senate majority to jam conservative jurists onto the high court. And it's also there on the left — in progressive demands that Democrats pack the Supreme Court, add reliably Democratic states to the union, and abolish the filibuster so the party can ram through an ambitious agenda with its own narrow Senate majority. Democrats barely control Congress, yet they want to govern as if it's 1937 or 1965, when they actually did command supermajority support in the country and in its legislature.

In such a situation, a proposal to scrap the Constitution and replace it with one that would give roughly half of the country sweeping policy victories at the level of foundational law while institutionalizing the total and permanent defeat of the other half on a huge range of issues is either a recipe for an unmitigated political catastrophe or an exercise in egregious self-delusion. Either way, it has nothing much to do with "democracy" and everything to do with winning.

That isn't a solution to our core political problem. It's a reenactment of our core political problem. Which means that the Democracy symposium offers no real solution at all.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?