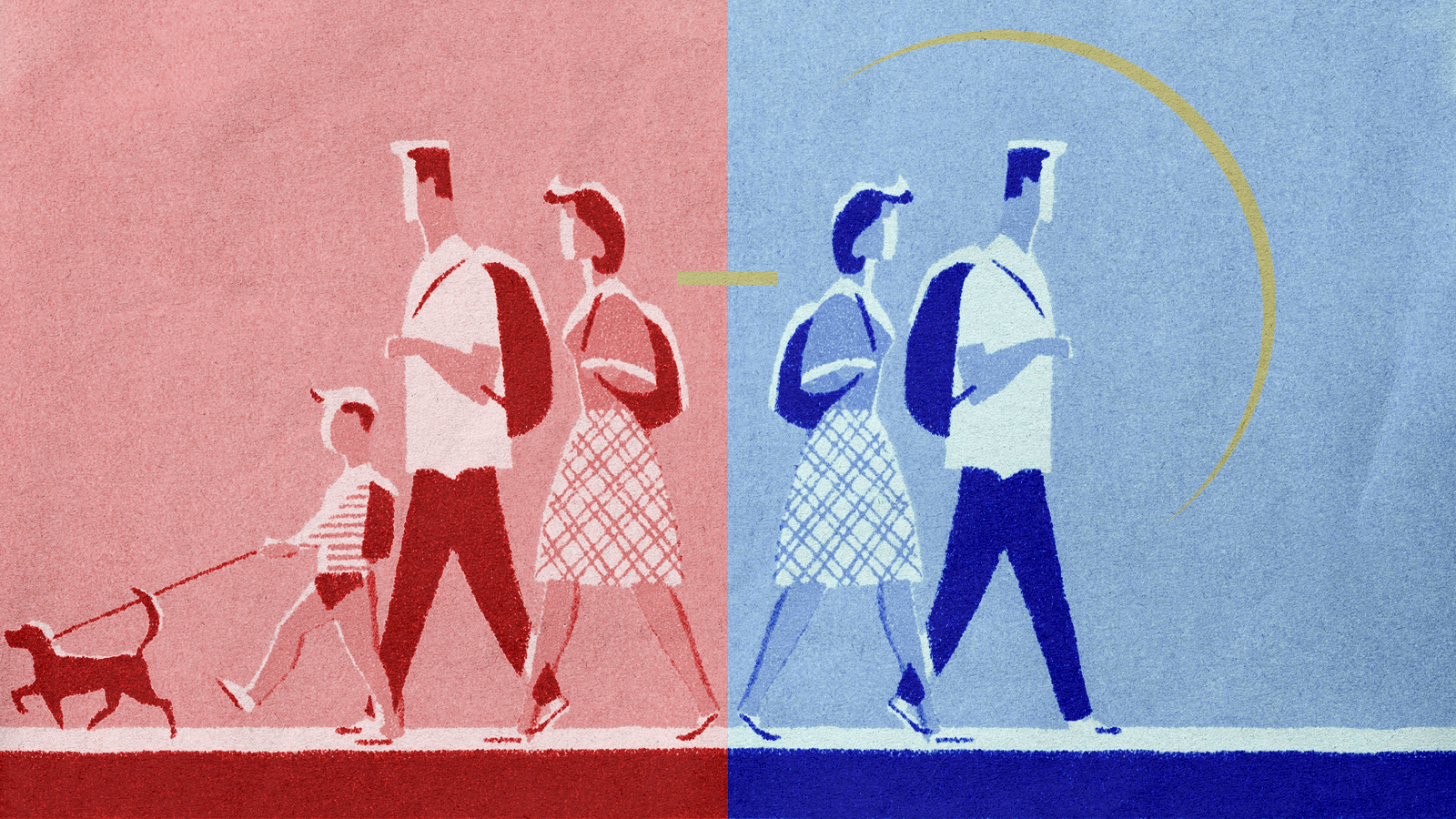

Are childless Americans really uninvested in the future?

Measuring the impact of declining birth rates on the American economy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The notion of giving parents extra voting power is one of those conservative ideas — like the flat tax and privatizing Social Security — that makes for an interesting thought experiment. But it's also one of those conservative ideas that seems a lot less interesting when politicians put their spin on it. Here's how Hillbilly Elegy author and U.S. Senate candidate J.D. Vance recently framed the issue at a conservative gathering: "Why is this just a normal fact of American life that the leaders of our country should be people who don't have a personal indirect stake in it via their own offspring, via their own children and grandchildren?"

Obviously Vance wasn't raising the issue like some think-tank wonk, noodling the pros and cons, costs and benefits. He seemed to mostly care about placing it in a partisan, "culture war" context to gain attention for his campaign. As Vance later told Fox News host Tucker Carlson, "We are running this country — via the Democrats, via our corporate oligarchs — by a bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives and the choices that they've made, and so they want to make the rest of the country miserable too. You look at Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg, AOC. The entire future of the Democrats are controlled by people without children." (Vice President Harris has two stepchildren, it should be noted.)

Silly stuff, really. To take just one aspect: All those Democrats say they are deeply concerned about climate change — unlike many GOPers — even though the worst impacts might not happen for decades or more. Yet once you peel away the needlessly inflammatory rhetoric, you'll find an intriguing economic issue: When societies start having fewer kids, do they also become less future-oriented in their policymaking? It's certainly a question worth pondering given the declining birth rates in many rich countries, including the United States. Indeed, the Wall Street Journal reports that U.S. population growth is now approaching zero, with a chance it might even turn negative this year. The decline goes back to the global financial crisis and economic downturn when the U.S. birth rate tanked and never recovered.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Thankfully, Vance's dystopian take on modern family preferences doesn't seem to be obviously supported by the evidence. Let's look at two economic factors: government indebtedness and infrastructure investment. Using them as markers for a forward-thinking society makes intuitive sense. Both fixing your roof while the sun is shining and curbing spending before the bill collector calls require foresight and a willingness to value "future you" over "current you." If the broad linkage suggested by Vance exists — lower societal fertility encourages short-termism — one might expect nations with lower fertility rates than the U.S. to have higher indebtedness and invest less in roads and bridges. And you would need such a linkage to be super strong before even toying with the illiberal idea of changing one person, one vote.

But that doesn't appear to be strongly or even obviously the case. Heading into the COVID-19 pandemic, plenty of rich countries with lower fertility rates than the U.S. also had a lower gross public debt-to-GDP ratio. Likewise, plenty of advanced economies with lower fertility rates spend a larger share of GDP on transportation infrastructure. Germany, for instance, has a lower fertility rate than the US (1.54 to 1.71), but also a lower debt ratio (68 percent to 134 percent) and spends a greater share of its economy on infrastructure (0.7 percent to 0.5 percent, as of 2019). Same goes for Great Britain and the Nordic countries.

Now this isn't to suggest all those economies, including America's, wouldn't be stronger with larger and faster-growing populations. "Other things equal, a larger population means more researchers which in turns leads to more new ideas and to higher living standards," explains Stanford University economist Charles Jones in his 2020 paper, "The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population." Societies that are older and growing more slowly also seem to generate fewer innovations and business startups. In the 2019 paper, "Demographic Origins of the Startup Deficit," researchers predicted that if present trends in U.S. fertility and immigration continue, the already depressed American startup rate "will remain near its current levels."

The obvious fix, then, is vastly increased immigration, something we know works versus efforts to boost fertility. Given its importance in the U.S. economy — supplying workers as well as entrepreneurs — a long-term perspective would want America to enlarge its role as a global magnet for the talented and ambitious. This assumes, of course, that the goal is improving national economic outcomes rather than personal political ones.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.