The promise and problem of a functional Federal Reserve

Two cheers for Jerome Powell. Now let's raise taxes on billionaires.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

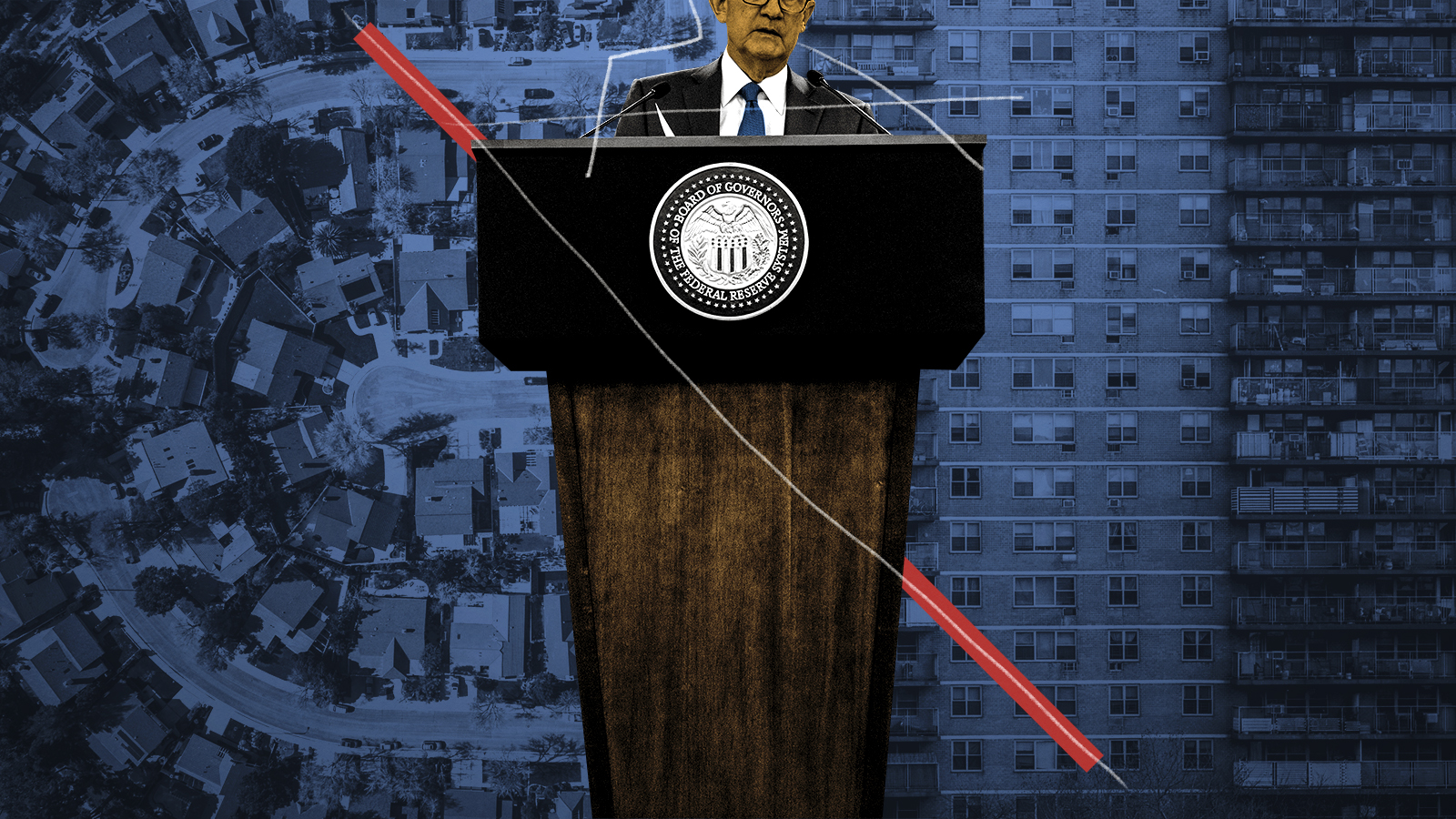

President Biden's Monday renomination of Jerome Powell for a second term as head of America's central bank, the Federal Reserve, isn't too surprising. Powell is broadly respected across most of the political spectrum and has largely been supportive of Biden's agenda of job creation and economic growth. Democrats also have only 50 seats in the Senate, and Powell is a Republican first appointed by former President Donald Trump. Despite that, he's evinced more concern for American workers of any Fed chair since Marriner Eccles in the 1930s and 40s.

Powell has also seen the Fed through some exceptionally rough times. Under his leadership, the bank was the key institution forestalling what would have been a cataclysmic financial crisis in March and April of 2020. While the rest of the American state performed like a rusting jalopy, the Fed was agile, proactive, and largely effective in containing the crisis. That contrast demonstrates the value of the Fed (and a good Fed chair), but it also shows the downsides of the Federal Reserve being one of the few high-performing parts of the American government.

Historian Adam Tooze tells the story of the Fed's early pandemic response in his excellent recent book Shutdown: How COVID Shook the World Economy. As the initial coronavirus shock gathered strength in March of 2020, economies and governments around the world were reeling. Businesses were thrown into chaos as their workers tried to stay at home, and that self-quarantine in turn caused a sudden collapse in demand for in-person services. States were scrambling for an effective public health response that wouldn't cause needless economic harm.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The big vulnerability for the Fed to address was an unusual and dangerous instability in the U.S. debt market. Normally, U.S. debt (issued as bonds that are commonly called "Treasuries") is the keystone asset of the global financial system. As Tooze explains, this is because so many institutions already have dollar-denominated debts or assets, and because the U.S. debt market is so deep and large. Prior to the pandemic, it was a safe assumption that U.S. debt was the one asset you could buy or sell in any quantity without changing the price — the safest asset in the world, and thus a key mechanism to manage risk.

In a normal recession, a flight to safety usually looks like everyone buying Treasuries. The price of stocks falls, and the price of American government debt rises. But that's not what happened in that March. Instead the price of stocks fell with the price of U.S. debt as foreign governments, trying to head off domestic disaster, liquidated their U.S. debt holdings to supply dollars to their domestic businesses and banks. Meanwhile, mutual and hedge funds, facing losses but unwilling to sell their stock holdings at a loss, sold their U.S. debt instead. And as chaos mounted, trading algorithms noticed and automatically reduced their buying of Treasuries.

The resulting instability in the debt market was dramatic. "On March 13, J.P. Morgan reported that rather than a normal market depth of hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. Treasuries, it was possible to trade no more than $12 million without noticeably moving the price," Tooze writes. "That was less than one-tenth of normal market liquidity."

Had this been allowed to continue, it would have created a financial crisis worse than 2008. Back then, a crisis in mortgage-backed assets created a sort of bank run within the U.S. and European financial system. That was bad enough. But the safety of Treasuries is the assumption undergirding virtually every economic entity on the planet. If U.S. debt were no longer safe, nothing would be.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Powell and his colleagues at the Fed tackled the crisis with aplomb. First, he slashed interest rates to zero.

Second, he bought hundreds of billions of dollars of U.S. debt and signaled he was prepared to buy more as needed, without limit. Rather than simply addressing a one-time problem, Powell's Fed acted as a market maker — ensuring a plentiful supply of dollars and a stable Treasury market for the indefinite future. "At the high point of the program, the Fed was buying bonds at the rate of a million dollars per second. In a matter of weeks, it bought 5 percent of the $20 trillion market," Tooze writes. This preserved financial stability, and it also de facto financed much of the gigantic CARES Act (though Powell and other Fed officials protested otherwise).

Third, Powell backstopped municipal and corporate debt markets — even lending to individual companies directly, which the Fed had never done before. City governments and companies like Boeing that were facing instant economic extinction found it possible to raise funds to tide them over for vital weeks or months.

Finally, Powell eased conditions on "swap lines" to other central banks around the world, which allowed them to trade their currencies for dollars and ease the pressure on their domestic economies. Asia especially needed this help. Effectively, just as in 2008, the Fed became the lender of last resort for the entire planet.

All this was vitally important in the pinch, and arguably Powell had few other options, at least given the scale and rapidity of the crisis, as well as the limitations of the existing Fed policy toolkit and political constraints. He couldn't have acted otherwise.

But the distributional consequences of all these actions were immense. Powell's response did not help all Americans equally. Saving the financial system and various corporate bond markets inflated the value of the stock market, which is overwhelmingly owned by the rich. As hundreds of thousands of Americans died of COVID-19, the billionaire class saw their wealth shoot into the ionosphere. The Fed's corporate debt rescue allowed large corporations to continue to stuff money into the pockets of their shareholders and executives while laying off their employees en masse.

I can draw two broad conclusions from this. First is that it would be nice to have other parts of the government that can function well in a crisis — particularly tax law and the IRS. All the Fed decisions that increased inequality could have been directly countered with increases in taxes on the rich, a windfall profits tax, and a broad attack on the legal chicanery that oligarchs use to hide their money overseas. Instead, the IRS has been starved of resources for a decade and barely bothers to even audit wealthy people anymore.

Inequality could also have been brought down indirectly through other congressional action: boosting the minimum wage, regulating abusive oligopolies, making it easier to form a union, increasing spending on welfare benefits, and so on. Instead, even with Democratic control of both Congress and the presidency, our sclerotic and dysfunctional legislature is barely managing to pass a smallish highway bill and a moderate package of welfare and climate policy — in which the single largest line item is a big tax cut for the rich. It's pathetic.

Second, the Fed's actions demonstrate something important about Wall Street. Twice in a bit over a decade the Fed has leapt into action to save the rickety and crisis-prone financial system — once from a disaster of Wall Street's own making, once from a surprise pandemic. That action was morally and politically justified insofar as it prevented a chaotic collapse of the global financial system, which would have unleashed untold economic carnage. But in the process, Powell demonstrated that the dollar-based financial system (which effectively extends across half the planet) is wholly dependent on the Fed to survive.

In the last analysis, contrary to decades of self-justifying myths from buccaneering financiers, Wall Street is an annex of American state power. And if it's worth invoking the awe-inspiring power of the dollar printing press to stave off a rapid collapse of the financial system because of the likely side effects, then it is worth using the same power to counteract the side effects of that system's normal operation — like offshoring, monopolization, corporate short-termism, union busting, and inequality.

We might start by giving every American a Federal Reserve account. The next time the Fed has to print up trillions of dollars, ordinary people could get a piece of the action.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred