Inflation isn't going away. That should make Biden very nervous.

The Great Inflation flashback in Wednesday's consumer prices report

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

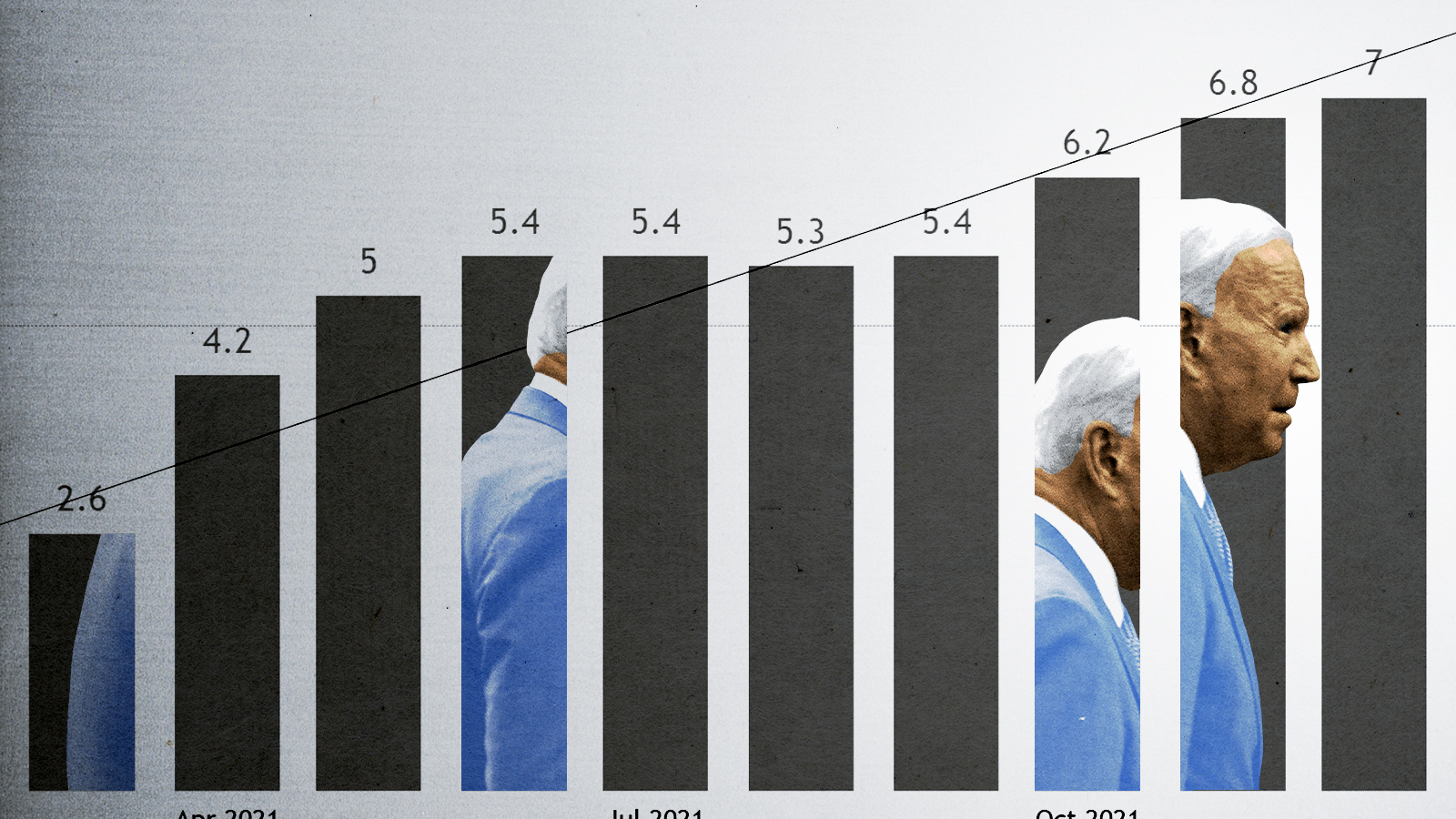

U.S. inflation hasn't been this persistently high since the last days of the Great Inflation between 1965 and 1982. Consumer prices rose 7 percent in December, the Labor Department said earlier today. That's the largest 12-month gain since June 1982, and the third straight month in which inflation exceeded 6 percent. What's more, core inflation — excluding food and energy, whose prices tend to jump around more — increased to 5.5 percent last month, with many economists expecting continued acceleration in the immediate future. "This is every bit as bad as we expected," said Capital Economics in a morning note to clients.

Maybe now is a good time to recall just how dismissive many on the left — from the Biden White House to Congress to think tanks — have been, arguing that higher inflation was no biggie. "Our experts believe and the data shows that most of the price increases we've seen … were expected, and expected to be temporary," said President Biden back in July. That sentiment was echoed by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.): "The price increases we're seeing are due to supply chain issues worsened by COVID. They are not permanent. We need to understand this. If we panic and raise interest rates, rather than strengthening infrastructure to help the supply chain, unemployment will go up."

The economic rationale mentioned by Ocasio-Cortez was hardly unreasonable. The global economy is reopening, and the global supply chain is having trouble adjusting. Inflation skeptics point to things like a semiconductor shortage as evidence of the one-off nature of the rise in prices. Eventually, supply chains will adjust. Indeed, the Federal Reserve held much the same opinion back then. Higher inflation was "transitory," said Chairman Jerome Powell.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But there was a political rationale, too. Republicans said rising prices, caused in large part by too much stimulus spending, showed Bidenomics was not only hurting the average American's pocketbook but was fundamentally unsustainable. Sure, the economy was growing at its fastest pace in decades and the unemployment rate was plummeting. But those were the things that were truly transitory. Invoking the name of Jimmy Carter, GOP politicians and pundits said it was the 1970s and early '80s all over again, when inflation eventually forced the Federal Reserve to cool things off by raising interest rates and pushing the economy into a deep recession.

Of course, Econ 101 — currently out of fashion for much of lefty EconTwitter — would have advised caution. Sustained inflation often looks like a short-term blip when it begins, perhaps caused by a temporary shortage somewhere in the economy. Oil back in the 1970s, chips today. But if inflation stays accelerated, consumers and business expectations can change. As Powell said Wednesday at his Senate confirmation hearing:

If inflation does become too persistent, if these high levels of inflation get entrenched in our economy and in people's thinking, then inevitably that will lead to much [higher rates] from us. And it could lead to a recession, and that would be bad for workers. So, really, achievement of maximum employment, by which we really mean continued progress in hiring and participation, is going to require price stability. High inflation is a severe threat to the achievement of maximum employment.

This is exactly why a few center-left economists like Larry Summers advised against the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill passed in March 2021. Too much money flowing into a supply-constrained economy would mean a sustained inflation spike and risk altering expectations. Of course, left EconTwitter vilified Summers.

But some Democrats, most notably the Biden administration, now realize inflation can't be dismissed. The president, for instance, has unpersuasively pointed to a lack of competition in the meat industry as a key factor pushing up food costs. And liberal economist Paul Krugman now concedes he got the inflation story wrong, telling readers of his New York Times column last month, "Even once the inflation numbers shot up, many economists — myself included — argued that the surge was likely to prove transitory. But at the very least it's now clear that 'transitory' inflation will last longer than most of us on that team expected."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Maybe inflation will yet settle down. And maybe the Fed will be able to navigate a "soft landing" where it's able to raise interest rates and shrink its bond portfolio enough to slow inflation without sinking the recovery. Biden, currently with a dismal 43 percent approval rating, better hope so. Recessions and inflation are a toxic political mix. Just ask one-termer Carter.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

‘They’re nervous about playing the game’

‘They’re nervous about playing the game’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugees

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugeesSpeed Read The memo also ordered all green card applications for the refugees to be halted

-

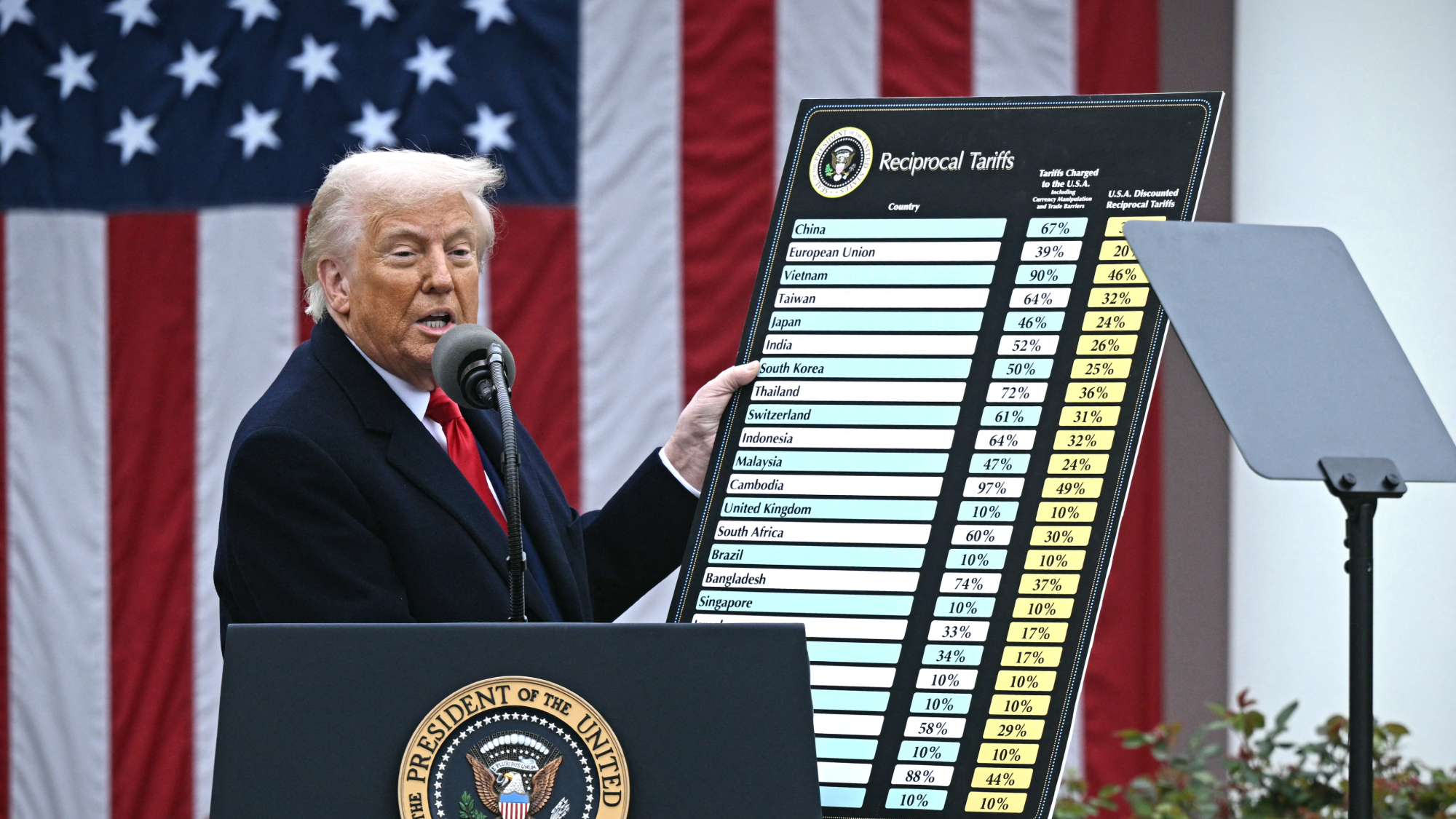

Tariffs: Will Trump’s reversal lower prices?

Tariffs: Will Trump’s reversal lower prices?Feature Retailers may not pass on the savings from tariff reductions to consumers

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June