Republican gerrymandering might come back to bite them

The GOP should take a long look at Irish history before gerrymandering their way to minority rule

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Will Republicans come to regret their embrace of gerrymandered maps entrenching minority rule instead of seeking to appeal to the majority of the population? The history of such practices in Northern Ireland suggests that they might.

On Monday, the Supreme Court rejected GOP requests to overturn state court decisions that imposed balanced congressional district maps in Pennsylvania and North Carolina. The move ensures the 2022 elections in those states will be fought within district boundaries that are largely untainted by the extraordinarily widespread practice of partisan gerrymandering.

This is welcome news for Democrats, but it's not a final decision. More importantly, it won't end the practice nationwide. The conservative majority on the Supreme Court already decided in 2019's Rucho v. Common Cause that partisan gerrymandering claims cannot be adjudicated by federal courts, as these claims represent a "political question." Monday's case exclusively concerns whether the Supreme Court would step in and rule that state courts, also, lack the right to prevent gerrymandering. For many states, that means legislatures will still be able to wildly distort electoral maps, and critics will have little to no legal redress.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That proliferation of counter-majoritarian institutions like partisan gerrymandering ensures that state governments are able to entrench their will upon future majorities of voters who wish to reverse their policies. Republican legislatures in purple Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania — all elected in the wake of the Democratic electoral collapse of 2010 — passed maps guaranteeing them success for a decade. This time around, Republican legislatures in Ohio, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas have passed maps that will prevent them from losing control even in the case of Democratic wave elections. Democratic gerrymanders exist in states like Maryland and New York, but the practice is generally understood to favor Republicans nationwide, particularly in battleground states.

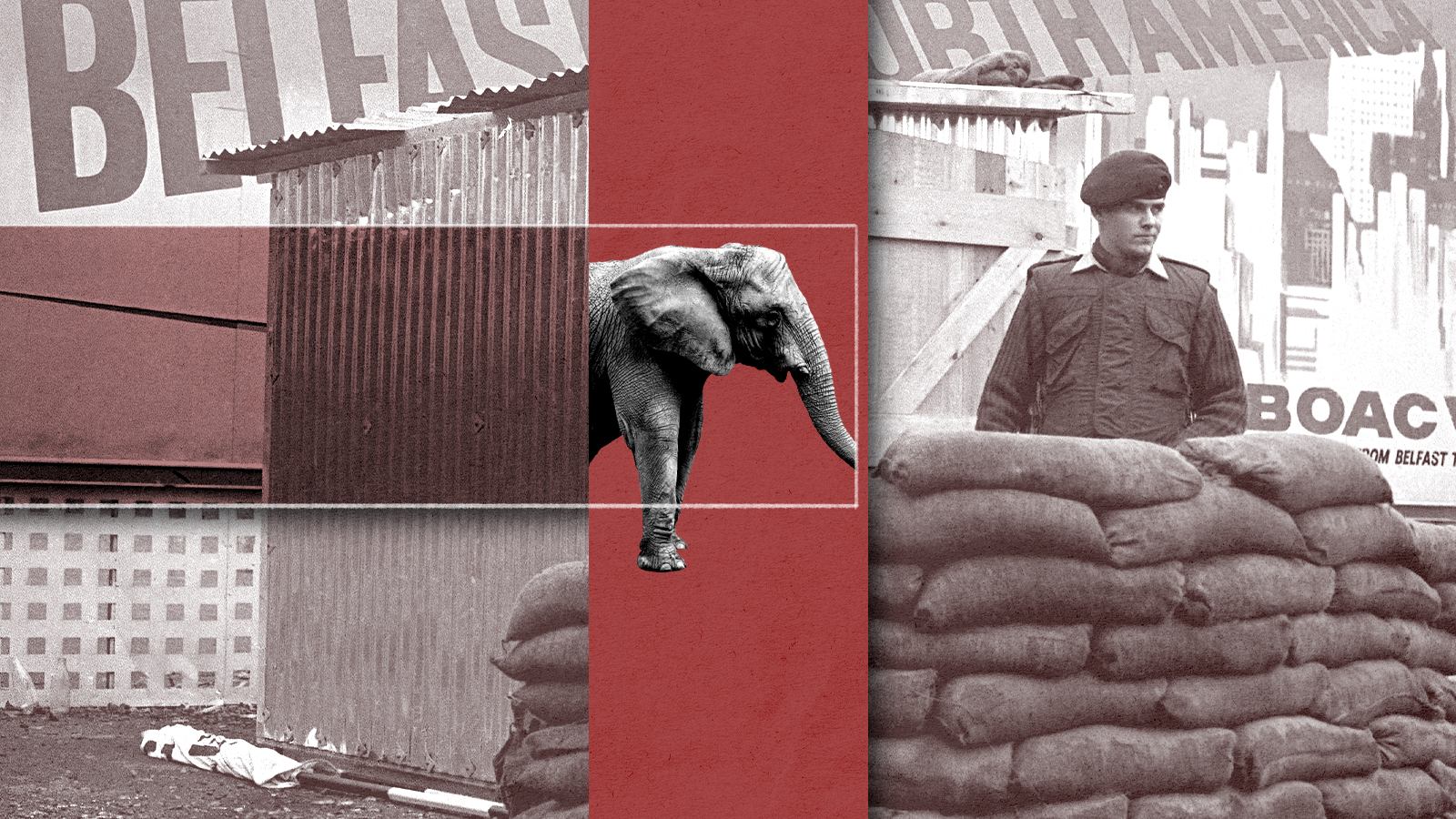

This will certainly benefit Republicans for the next decade or two, but the history of gerrymandering in my native Ireland shows it may well come to hurt them in the long run. The Northern Irish unionist majority, largely Protestant, spent decades imposing gerrymandered maps in their local elections. In Derry, the notorious 1968 elections saw Catholic nationalists win 60 percent of the votes only to receive 40 percent of the seats.

The practice ensured the nationalists were angry at being disenfranchised. But it also meant the ruling unionists didn't need to appeal to anyone outside their own minority constituency in order to win. Catholics, packed into a small minority of districts, could be safely ignored, ensuring that competition for power would rely exclusively upon satisfying the desires of the Protestant population.

This sort of imbalance has destructive effects on any democracy, where politicians are supposed to be incentivized to serve the whole community through the need to appeal to them for votes. First, it ensures the ruling population has little reason to moderate its demands or seek compromise, encouraging a spiral towards ever more hardline positions. On the other side, the disenfranchised population increasingly comes to see the political system as incapable of meeting their demands — not just for equal political rights, but also for equal treatment in government services and spending.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The first recourse is usually protest, which occurred in Northern Ireland with the peaceful Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association demonstrations. But if those efforts are unsuccessful, it is often the case that some section of the disenfranchised population will turn to violence. As Irish civil rights leader Bernadette Devlin made clear to William F. Buckley in a 1972 interview, whether one believes such violence to be moral or not, it is a predictable consequence of an anti-democratic system.

The system of gerrymandering in Northern Ireland did not end until decades later, but it did end. The Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which stopped the armed conflict, is not something unionist majorities in the first half-century of Northern Ireland's existence could have ever intended. It required proportional representation in elections, extensive affirmative action in favor of Catholics in most state institutions, all-Ireland institutions for cooperation on many matters, an amnesty for convicted IRA members, and a Northern Irish constitution that permanently guaranteed power to be shared equally between nationalists and unionists.

The lessons for American politics are clear: Blowback from decades of anti-democratic practices can, in the end, be worse for those profiting from those practices than the compromises they would have needed to appeal to moderates and win a majority. Societies unquestionably benefit from having stable, democratic elections in which politicians compete for every vote and all sides feel the winners are legitimate.

Closing off electoral avenues for a majority of voters to secure change may push some of your opponents to adopt tactics that — while many may find them to be disgraceful — are also sometimes successful. South Africa's Nelson Mandela is remembered as a peacemaking president, but he made that peace as leader of an armed resistance movement against minority rule. Martin McGuinness, once an IRA fighter, died as deputy first minister of Northern Ireland.

With that history in mind, Republican legislators might do well to wonder whether suppressing Democratic voters in battleground states may eventually lead to their governing alongside the Marxist BLM rioters they fear.

Saoirse Gowan is a writer and researcher with a focus on public policy from a left perspective. She was born and raised in Ireland by an American mother and Irish father, and moved to Washington, D.C. in 2018. She currently lives in Hyattsville, MD, and spends her free time on art and dancing.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

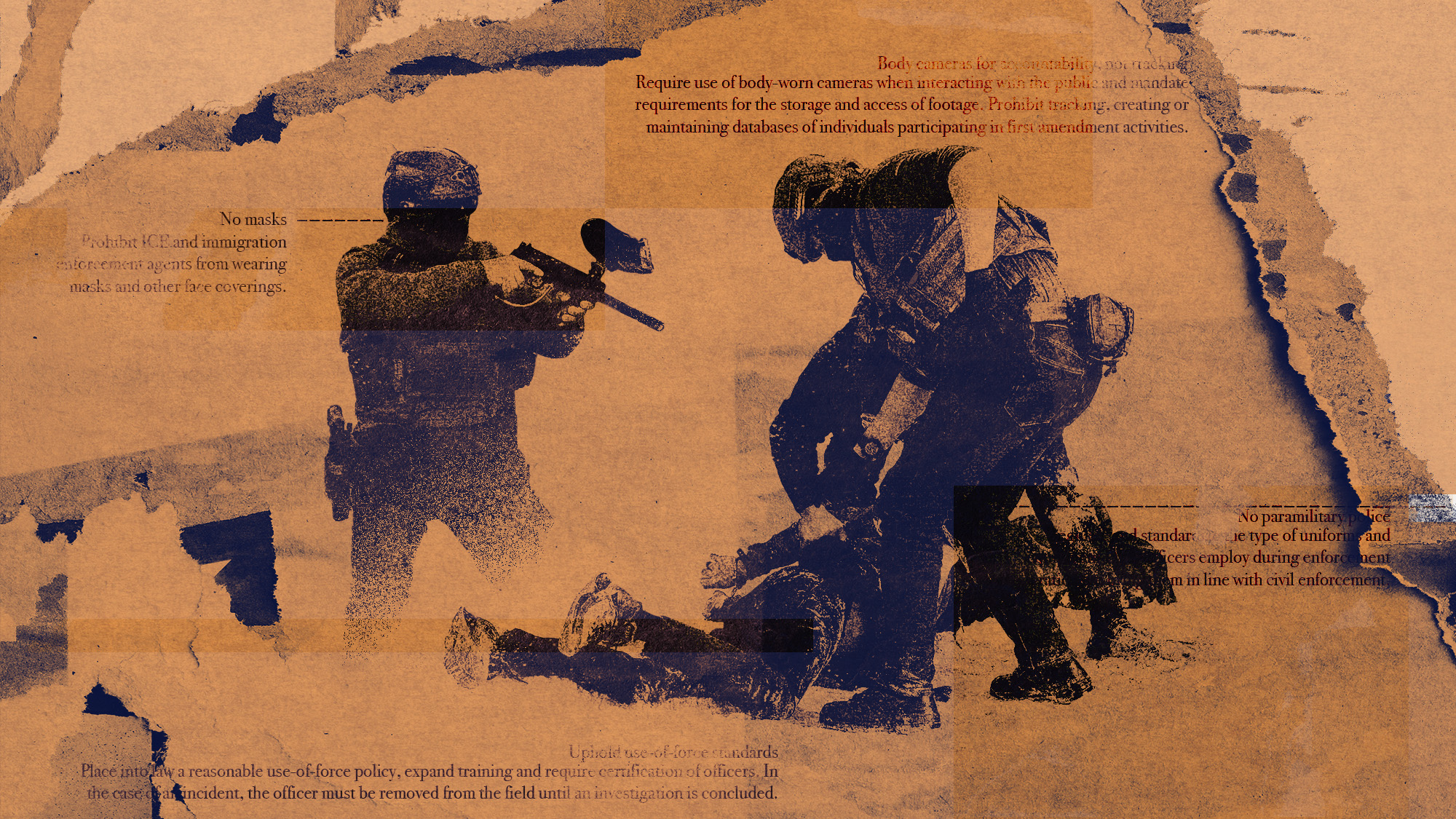

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

Halligan quits US attorney role amid court pressure

Halligan quits US attorney role amid court pressureSpeed Read Halligan’s position had already been considered vacant by at least one judge

-

House approves ACA credits in rebuke to GOP leaders

House approves ACA credits in rebuke to GOP leadersSpeed Read Seventeen GOP lawmakers joined all Democrats in the vote

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story