Putin's messianic mission

The autocrat's Darwinian worldview was shaped by a grim childhood, the KGB, and the fall of the Berlin Wall

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The autocrat's Darwinian worldview was shaped by a grim childhood, the KGB, and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Here's everything you need to know:

How did Putin grow up?

Born in 1952, Putin spent his childhood in St. Petersburg (then called Leningrad), in the shadow of World War II. During the Nazis' 871-day siege of Leningrad, more than a million citizens died; starvation drove some people to cannibalism. Putin's father was a factory worker and devoted Communist who'd reportedly worked for the NKVD, the party's feared law enforcement arm. Putin grew up in a communal apartment in a drab housing complex where he and his friends chased rats in the hallways for amusement. The short, scrawny boy was bullied, driving him to take up judo and sambo, a Soviet martial art that teaches participants to remain stoic even in the face of great pain. Wily and inscrutable, Putin earned a reputation as a ruthless street fighter unafraid to take on far larger opponents. He learned, he later wrote, that when threatened, "You must hit first, and hit so hard that your opponent will not rise to his feet."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When did he become a spy?

Taken as a boy by depictions of brave, resourceful agents in books and movies, Putin knew at a young age he wanted to join the KGB, and reportedly asked about signing up while still in high school. His attraction to the Gestapo-like agency during "the height of KGB repression against the Soviet dissident movement" speaks volumes, said Rutgers political scientist Alexander Motyl. Recruited after studying law at Leningrad State University, Putin was evaluated during his training as a risk-taker with an unusually low sense of fear, according to Putin's own account. KGB officers were trained to be predatory, inscrutable, and devoted above all to the Russian state. After several years in Leningrad, he was sent to Dresden, East Germany, in 1985. There he had what is often called the most pivotal experience of his life.

What was it?

Watching the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. Holed up in the KGB headquarters, Putin, then 37, grew panicked as he watched crowds march on the headquarters of the Stasi, the East German secret police, and then begin to gather outside the KGB's villa. As his colleagues frantically burned documents, Putin made a desperate call to the Soviet military command for help. To his profound shock, none was forthcoming. "I got the feeling then that the country no longer existed — that it had disappeared," Putin said years later. His feelings of betrayal and humiliation intensified with the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union. Putin drew several formative lessons from his Dresden experience. It instilled in him a loathing for democratic mobs and a bitter resentment of the West. It taught him, he said last month, that even a momentary "paralysis of power" is "the first step toward complete degradation and oblivion." And it implanted in him a driving obsession that lies behind his stunning aggression in Ukraine.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What is this obsession?

To avenge Russia and restore its lost glory. "In his mind, Mr. Putin finds himself in a unique historical situation in which he can finally recover for the previous years of humiliation," said Russian journalist Mikhail Zygar. Russia's return to superpower status, Putin has said, starts with his total control over a "supercentralized" state. The next phase is reassembling a Russian-speaking empire within the former Soviet Union's borders. To see Ukrainians building a Western-style democracy within those old borders is a "mortal threat to his imperial ambitions," said Motyl of Rutgers. Some Putin analysts also point to a religious dimension to Putin's vision.

What role does religion play?

Putin has embraced the Russian Orthodox Church as a core element of nationalistic Russian identity. He wears a baptismal cross and is shown in state media engaging in religious rites. The church's leaders share his vision not only of a morally decaying West but of restoring a svyataya Rus — Holy Russia — that extends to Russian Orthodox believers in former Soviet republics. As the site of the founding of Russian Orthodoxy, Kyiv holds great significance, and church leaders were affronted when in 2019 the Ukrainian Orthodox Church asserted its independence from the Patriarchate of Moscow, whose jurisdiction it had been under for centuries. The nationalistic head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Kirill, has formed a close bond with Putin, calling him a "miracle from God." The extent to which Putin sees himself as a messianic figure on "a spiritual quest" to save Russia is underappreciated by many in the West, writes British journalist Giles Fraser. In the face of such a vision, he writes, it's deluded to think "that a bunch of sanctions is going to make a blind bit of difference."

A strongman's worst nightmare

Like all autocrats, Putin has one principal fear: being overthrown. Dictators do not head off to a comfortable retirement when their citizens rise up against them, and the deaths they suffer are often savage and humiliating. Putin analysts say he's particularly fixated on the gruesome end of Libyan strongman Moammar Gadhafi, a longtime client of Russia's. After Gadhafi's regime collapsed in October 2011, the brutal former dictator was dragged by a mob from a drainage pipe in which he'd been hiding, and begged for his life before being tortured and then shot repeatedly by a jeering throng. His mangled body was then placed on public display. The horrific scene was captured on a cellphone video — one Putin is said to have watched obsessively. "That's his worst nightmare," said Douglas London, a retired 34-year veteran of the CIA. It certainly isn't lost on Putin that Gadhafi's downfall followed a NATO-led intervention designed to protect civilians during the First Libyan Civil War. The episode "helped crystallize Putin's distrust of the West" as well as "his own sense of vulnerability," said Kim Ghattas in a recent article in The Atlantic. The lesson he drew "is a dire one for Ukraine," she writes: "Backing down or making any concessions is a death sentence."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ comes into confounding focus

Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ comes into confounding focusIn the Spotlight What began as a plan to redevelop the Gaza Strip is quickly emerging as a new lever of global power for a president intent on upending the standing world order

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guarantee

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guaranteeTalking Points Zelenskyy says it is a requirement for peace. Will Putin go along?

-

What have Trump’s Mar-a-Lago summits achieved?

What have Trump’s Mar-a-Lago summits achieved?Today’s big question Zelenskyy and Netanyahu meet the president in his Palm Beach ‘Winter White House’

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

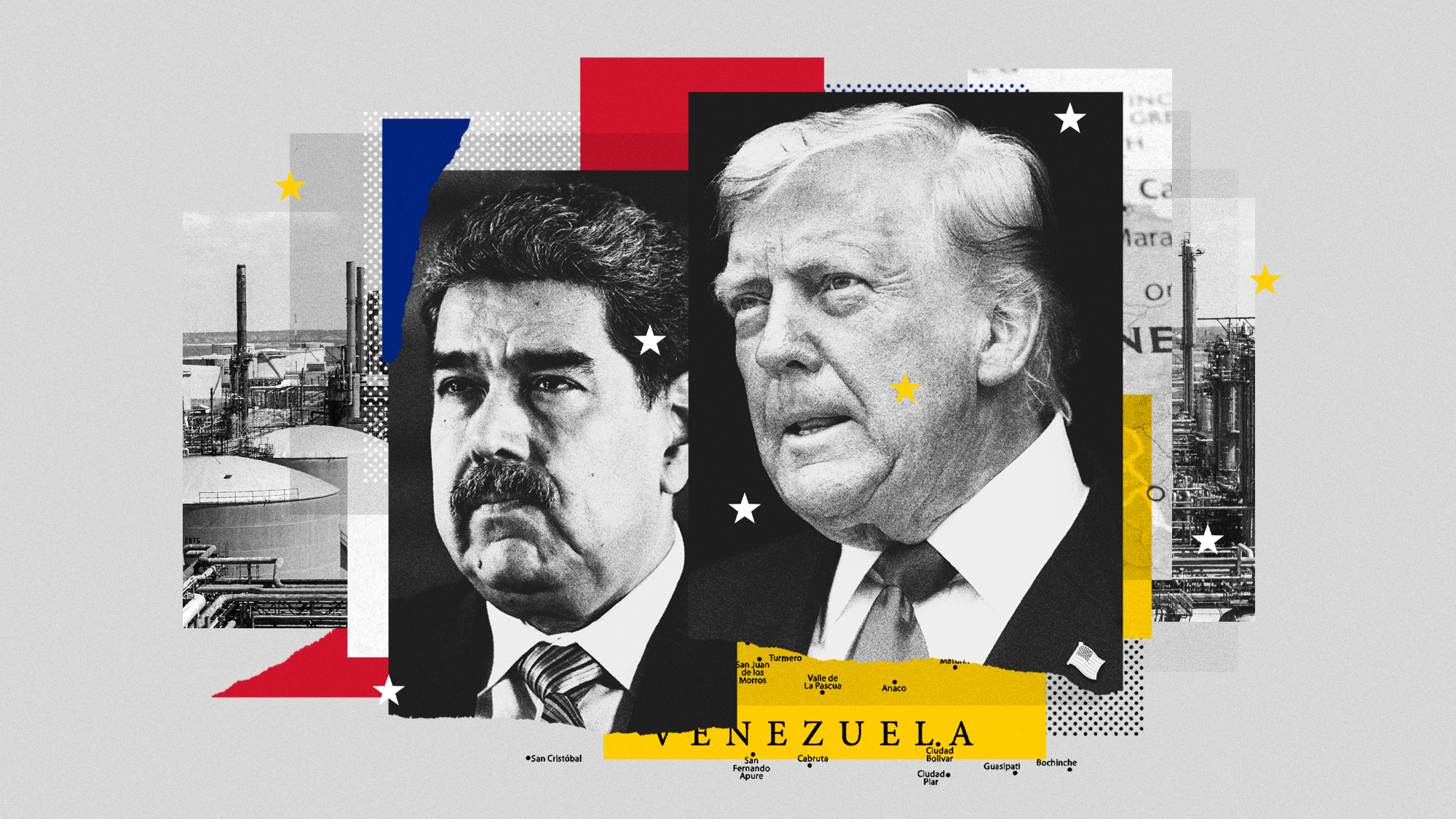

Why, really, is Trump going after Venezuela?

Why, really, is Trump going after Venezuela?Talking Points It might be oil, rare minerals or Putin

-

Moscow cheers Trump’s new ‘America First’ strategy

Moscow cheers Trump’s new ‘America First’ strategyspeed read The president’s national security strategy seeks ‘strategic stability’ with Russia