How do the Iowa caucuses work?

Where did the Iowa caucus come from, how does it work, and why is it so important?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Iowa Republicans are voting Monday in their presidential caucus, the first step in the process of choosing the party's presidential candidate to face the likely Democratic nominee, incumbent President Joe Biden. Following the Iowa caucus, the next state to vote will be New Hampshire, which holds a direct primary on Tuesday, Jan. 23. Iowa and New Hampshire have been the first states to hold their nominating contests since the parties granted more control over presidential nominations to their voters beginning in 1972, and the results there have often, although not always, been consequential, despite the relatively small total number of delegates to the national nominating conventions that are at stake. Where did the Iowa caucus come from, how does it work, and why is it so important?

What is a caucus?

A caucus is a unique way of conducting elections, involving voters showing up at a set location at a specific time and engaging in a relatively long deliberative process. Iowa has used caucuses in the presidential nominating process since the 19th century, although until the 1970s results were not considered binding on delegates to the parties' nominating conventions. In the context of national party politics, a caucus is now a highly unusual form of voting for Republican and Democratic presidential nominees, with only Iowa, Nevada, Wyoming and North Dakota continuing to use this form of voting.

Defenders of the caucus system like Krist Novoselic note that a caucus is "a community event run by volunteers" that avoids the influence of consultants and media strategists, critics describe them as elitist and exclusionary, since people who can't afford to spend the time caucusing may not be able to participate. As Suffolk University political scientist Rachael Cobb wrote in 2020, abolishing caucuses would "expand the electorate, make the results more representative and eliminate the challenges associated with" having important elections administered by party activists rather than professionals. Most other states have adopted the direct primary system, in which voters are simply asked to vote for their preferred candidate without having to potentially devote hours to a meeting.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The idea that voters should pick their party nominees for president gained steam over the course of the 20th century, but even through the 1968 cycle nominees were picked by party insiders at their respective nominating conventions. Since the parties moved toward binding processes for primaries and caucuses beginning in 1972, Iowa has been the first state to vote, less a deliberate choice than a historical accident. And it's a privilege that the Democrats effectively revoked after an embarrassing fiasco in 2020 made it difficult to declare a winner. Iowa Democrats had previously beaten back every attempt to move or change the state's caucus.

Just as the caucus process has legions of detractors, so does the idea that Iowa and New Hampshire — small, overwhelmingly white states — should have such outsized influence on the nominating process. As the Brooking Institution's Elaine Kamarck writes in her history of the presidential nominating process, Primary Politics, "Neither Iowa nor New Hampshire set out to dominate American presidential nominating politics. But once the dynamics of the modern nominating system thrust them into the spotlight, they grew fond of their place and held onto their positions fiercely."

While President Biden technically has two challengers (Dean Phillips and Marianne Williamson) on the Iowa ballot, they are not considered viable candidates and the party is not hosting or sponsoring debates or events. The Iowa Democratic caucus this year is a mail-in ballot event whose results will be revealed on March 5 to coincide with Super Tuesday. With Democrats not holding a meaningfully competitive nomination contest, Iowa Republicans have the stage more or less to themselves. And Iowa's position on the calendar has caused no such controversy on the political right, where the state's demographics are much more representative of the party coalition than they are for Democrats.

How it works

Republicans and Democrats use somewhat different rules for their caucuses in Iowa. Democrats through 2020 had supporters of candidates stand in different parts of the room for speeches and persuasive efforts following an initial tally, after which non-viable candidates were eliminated and their supporters dispersed to second-choice candidates, known as "realignment" Crucially, person-to-person politicking followed the initial tally. Voters also had the opportunity to leave if their candidate was eliminated and not move to someone else's corner. Final tallies were then turned into "state delegate equivalents" and estimated vote shares. Republicans use a far simpler process. For the GOP primary, voters gather together at their local precinct or voting place by 7 p.m., hear speeches in support of various candidates and then vote once before departing. Results will be posted that night.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Any eligible voter can register at their caucus site or even change their registration to Republican to participate on the night of the event. That has led to speculation that former President Donald Trump's challengers might seek support from independents and Democrats who want to see Republicans nominate someone else. Trump's chief rival according to current polling, former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, has said her campaign is not pursuing that strategy, but Super PACs (independent groups that can support specific candidates but may not coordinate strategy with them) backing Haley have made a push to target independents.

What's at stake

Trump holds a commanding lead with both national Republican primary voters as well as in surveys of Iowa, according to Real Clear Politics averages. But presidential nominees are not chosen nationally, and momentum from unexpected victories in early contests has altered the dynamics of races many times in the past. So even though there are just 40 delegates at stake in Iowa (out of a total number of 2,429), which will be awarded proportionally to the candidates depending on their share of the vote, the campaigns are spending significant resources there, aiming to claim victory or momentum (or both). Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) has held more than 90 events in Iowa and hopes to turn that investment into a surprise showing on Sunday night. Biotech entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy has visited Iowa the most, but that attention has so far failed to translate into a polling surge.

Trump will be looking for a knockout blow, a decisive victory that leaves his two plausible challengers — DeSantis and Haley — on the ropes and scrambling for narrative oxygen heading into New Hampshire. Haley's best chance to fundamentally alter the trajectory of the race probably rests on a strong second-place finish in Iowa and then using that momentum as a springboard into an outright win in New Hampshire. Whether that would influence GOP voters in the next states to vote (Nevada and the Virgin Islands on Feb. 8 and then South Carolina on Feb. 24) is anyone's guess. But she'll need more than moral victories as Super Tuesday approaches on March 5. DeSantis is polling distant fourth in New Hampshire, and anything less than second place in Iowa could be fatal to his campaign. Whatever the outcome on Monday, expect the candidates who choose to continue campaigning to furiously spin their results in their favor.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities

-

A running list of everything Trump has named or renamed after himself

A running list of everything Trump has named or renamed after himselfIn Depth The Kennedy Center is the latest thing to be slapped with Trump’s name

-

A running list of the international figures Donald Trump has pardoned

A running list of the international figures Donald Trump has pardonedin depth The president has grown bolder in flexing executive clemency powers beyond national borders

-

A running list of US interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean after World War II

A running list of US interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean after World War IIin depth Nicolás Maduro isn’t the first regional leader to be toppled directly or indirectly by the US

-

A running list of the US government figures Donald Trump has pardoned

A running list of the US government figures Donald Trump has pardonedin depth Clearing the slate for his favorite elected officials

-

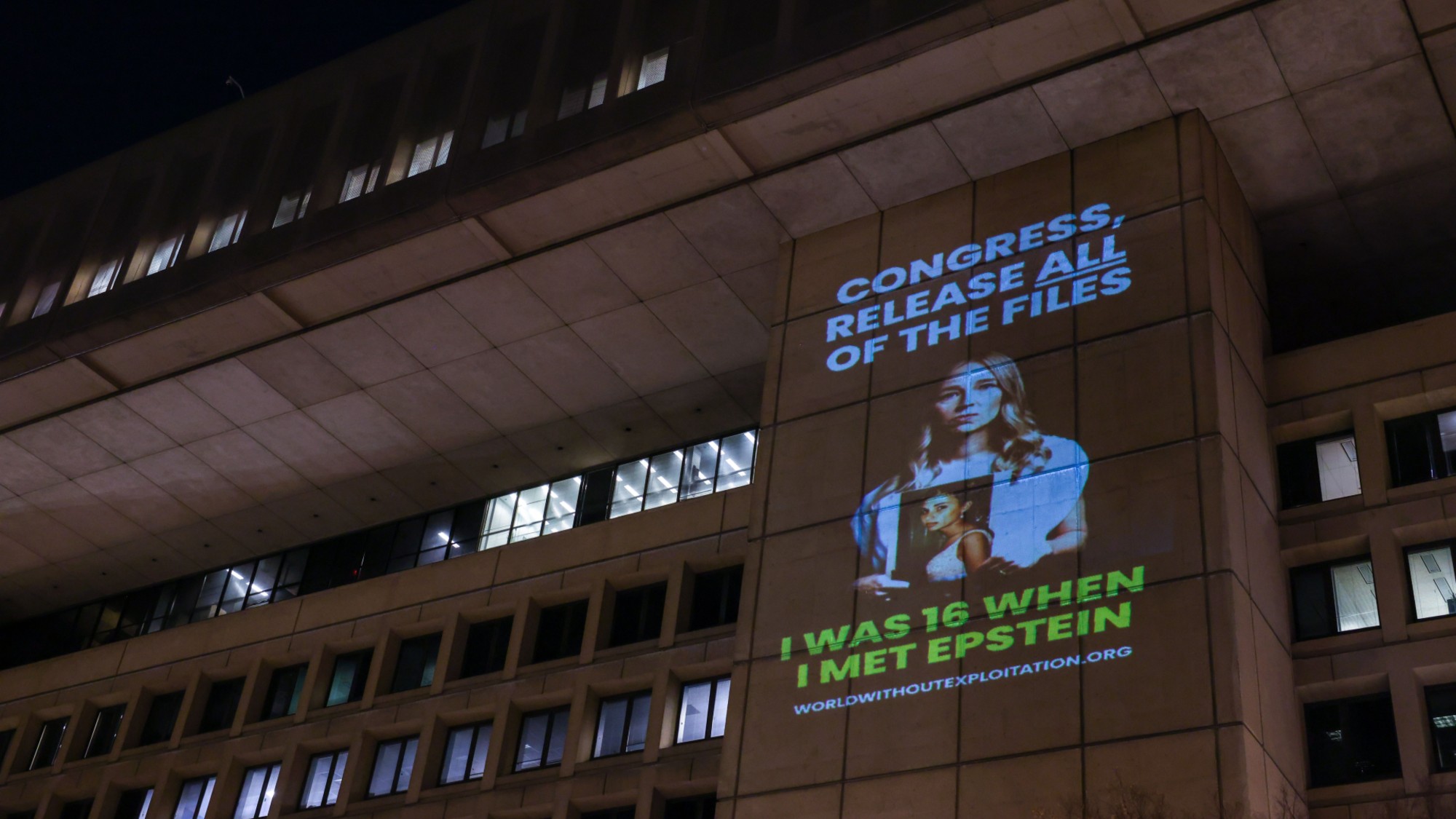

The powerful names in the Epstein emails

The powerful names in the Epstein emailsIn Depth People from a former Harvard president to a noted linguist were mentioned

-

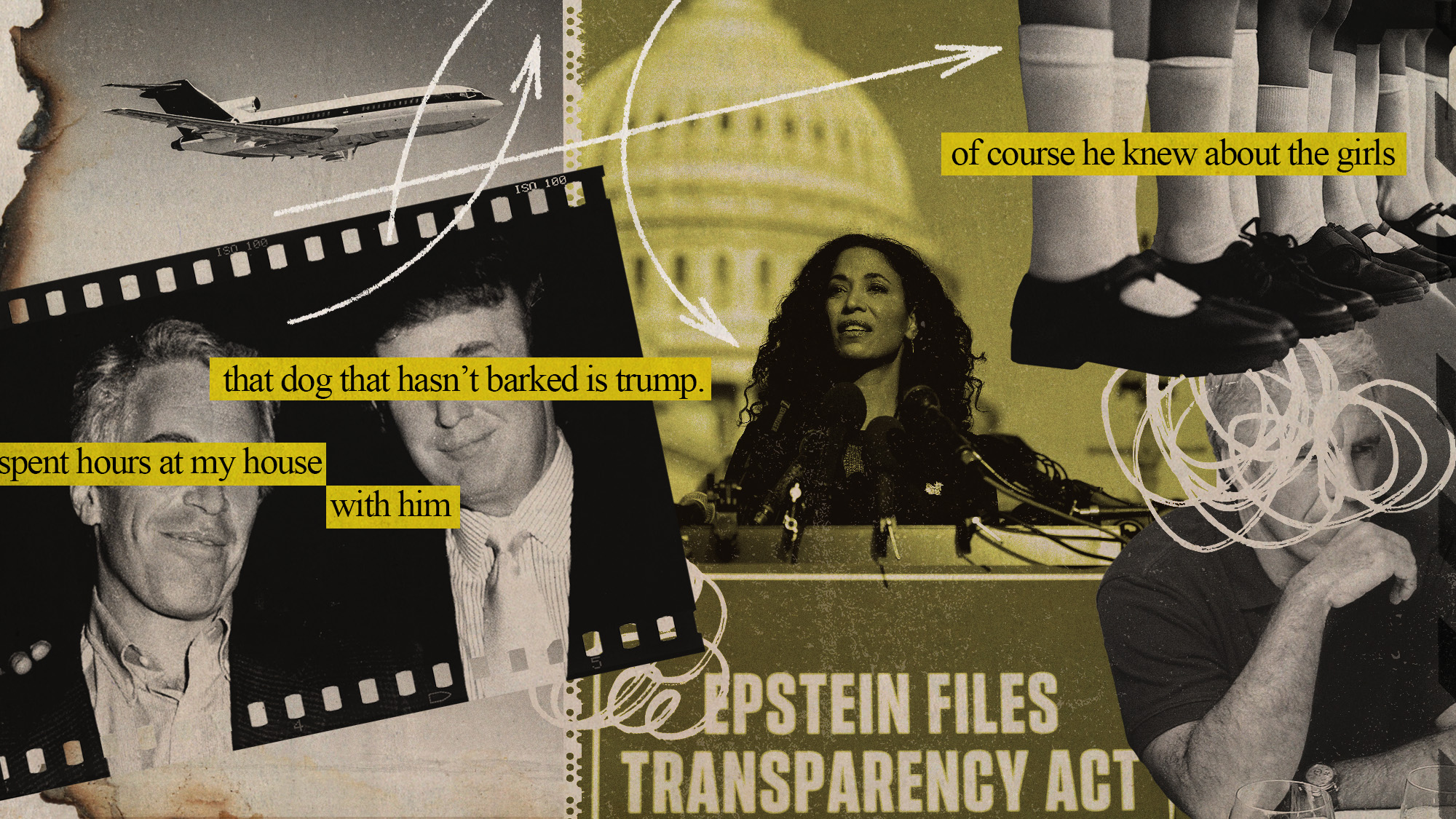

Donald Trump and Jeffrey Epstein: a Timeline

Donald Trump and Jeffrey Epstein: a TimelineIN DEPTH The alleged relationship between deceased sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein and Donald Trump has become one of the most acute threats to the president’s power

-

A running list of the famous people Donald Trump has pardoned

A running list of the famous people Donald Trump has pardonedIN DEPTH Reality stars, rappers and disgraced politicians have received some of the high-profile pardons doled out by the president