India elections 2024: the logistics of world's biggest vote

More than 10% of the world's population is registered for a historic democratic exercise, with PM Modi likely to dominate again

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

India heads to the polls this month for a democratic exercise "unmatched in scale" either historically or globally.

"From the Himalayas in the north to the Indian Ocean in the south, from the hills of the east to the deserts in the west… an estimated 969 million voters are eligible to cast their ballots," said Al Jazeera. That is more than 10% of the world's population. For context, that's more than the population of the EU, US and Russia combined.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, leader of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) since 2014, is gunning for a third term in office at the helm of the world's most populous country – and the fastest growing economy – of more than 1.4 billion people.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How does it work?

The election will take place in seven phases, starting on 19 April and ending on 1 June, according to the Election Commission of India, with results expected on 4 June.

The length of time needed is due to the "sheer size" of India, and the "astonishing levels of logistics" needed to ensure every voter can cast a ballot, said The Associated Press (AP).

Electoral rules state that there must be a booth within two kilometres of each voter, which means that officials have to cross deserts and mountains to reach remote areas. In 2019, India's last elections, one team of polling officers trekked more than 480 kilometres to reach a "single voter in a hamlet", said AP.

Another concern is security after "deadly clashes" between supporters of rival parties marred previous elections.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This year a "15 million-strong army" of polling officials and security forces will oversee the "gigantic" 44-day exercise, at more than a million polling stations, with the help of 5.5 million electronic voting machines, said Sky News.

Each of the 28 states and eight federal territories will vote to fill the 543 seats of the Lok Sabha (lower house). To secure a majority and form a government in this first-past-the-post system, a party or coalition needs to win at least 272 seats.

About 25% of those are reserved for members of two "disadvantaged communities", said Sky News – 84 seats go to those from "scheduled castes", known as Dalits, and there are 47 seats for "scheduled tribes", or Adivasis.

India recently passed a measure to reserve a third of the seats for women, but implementation was delayed until after 2024.

Who are the main parties?

There are two main factions in parliament. Modi's BJP leads a centre-right coalition of more than three dozen parties, known as the National Democratic Alliance.

It will face off against the India National Congress party, known as Congress. It has clubbed together with about 24 other political parties to form an opposition bloc known as INDIA (Indian National Development Inclusive Alliance).

The alliance has been "roiled by ideological differences and personality clashes", said AP News, and has yet to select its candidate for prime minister.

What are the stakes?

"The world's largest democratic election could also be one of its most consequential," said AP. It is seen as a "test for the country's democratic values".

Last year a Pew survey found that nearly 80% of Indians viewed Modi, an "avowed Hindu nationalist", favourably. Supporters "hail him as a transformative leader" whose powerful mix of religious identity and modernisation has "propelled him away ahead of his challengers", said Sky News.

But Modi is "loathed" by others, with critics decrying him as "representing an Indian variant of fascism". Under his rule institutions of secular and democratic India have been "vastly eroded", dissent stifled and the Muslim minority – about 14% of the population – increasingly stigmatised.

What's likely to happen?

In 2019, the BJP won 37.36% of the votes, resulting in a majority of 303 seats – the highest vote share by any political party since 1989.

This year, the coalition Modi leads could win nearly three-quarters of the parliamentary seats, while Congress could hit a record low, according to an India TV-CNX opinion poll published on Wednesday, said Reuters.

The "immensely popular" prime minister is "riding high on the back of strong economic growth, handouts and the January inauguration of a Hindu temple on a contested site", said Reuters. That's despite rising unemployment and "widening disparity between the rich and poor".

If Modi wins and completes another five-year term, he will be the third longest serving prime minister in Indian history.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant US intelligence

-

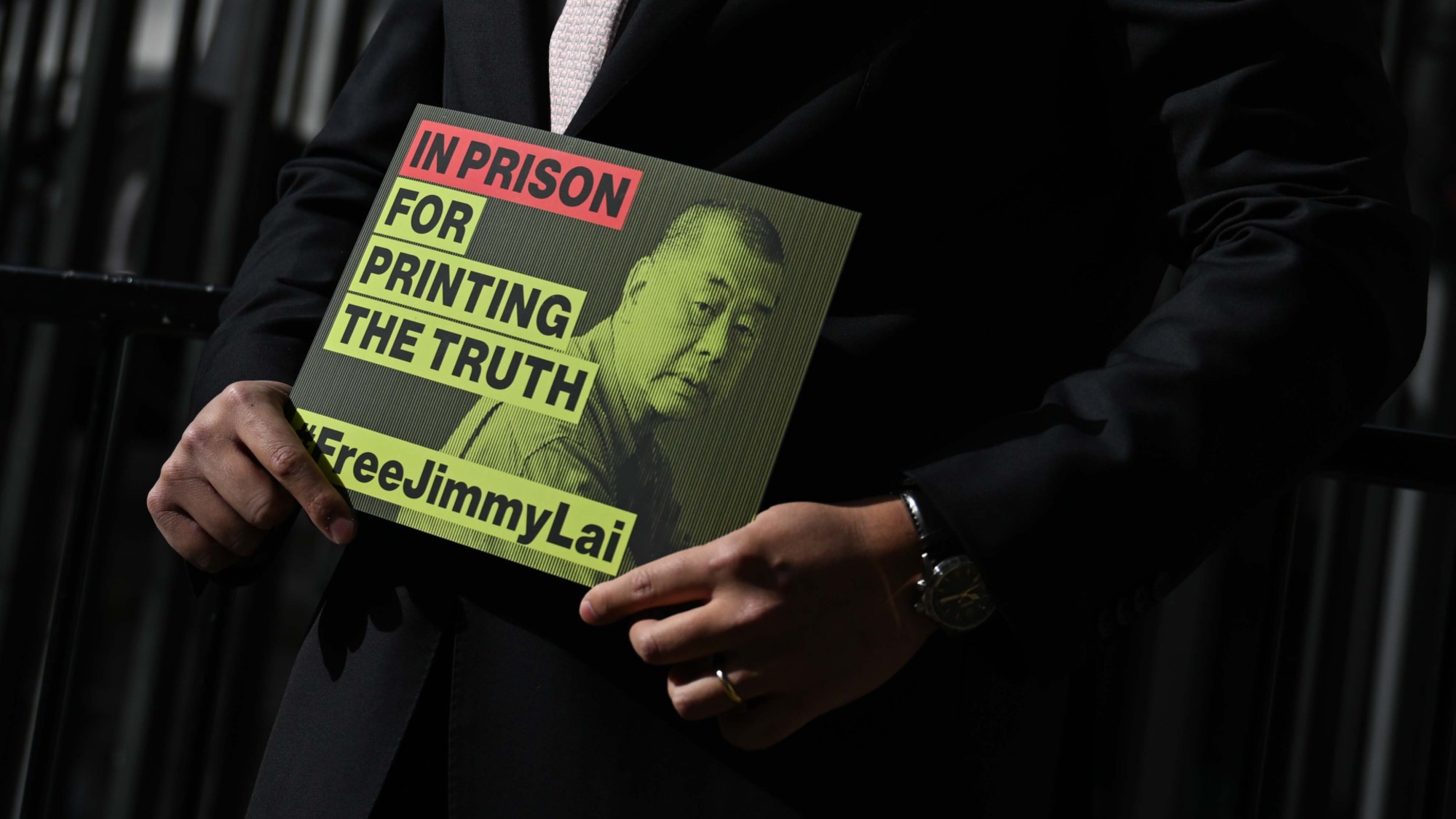

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

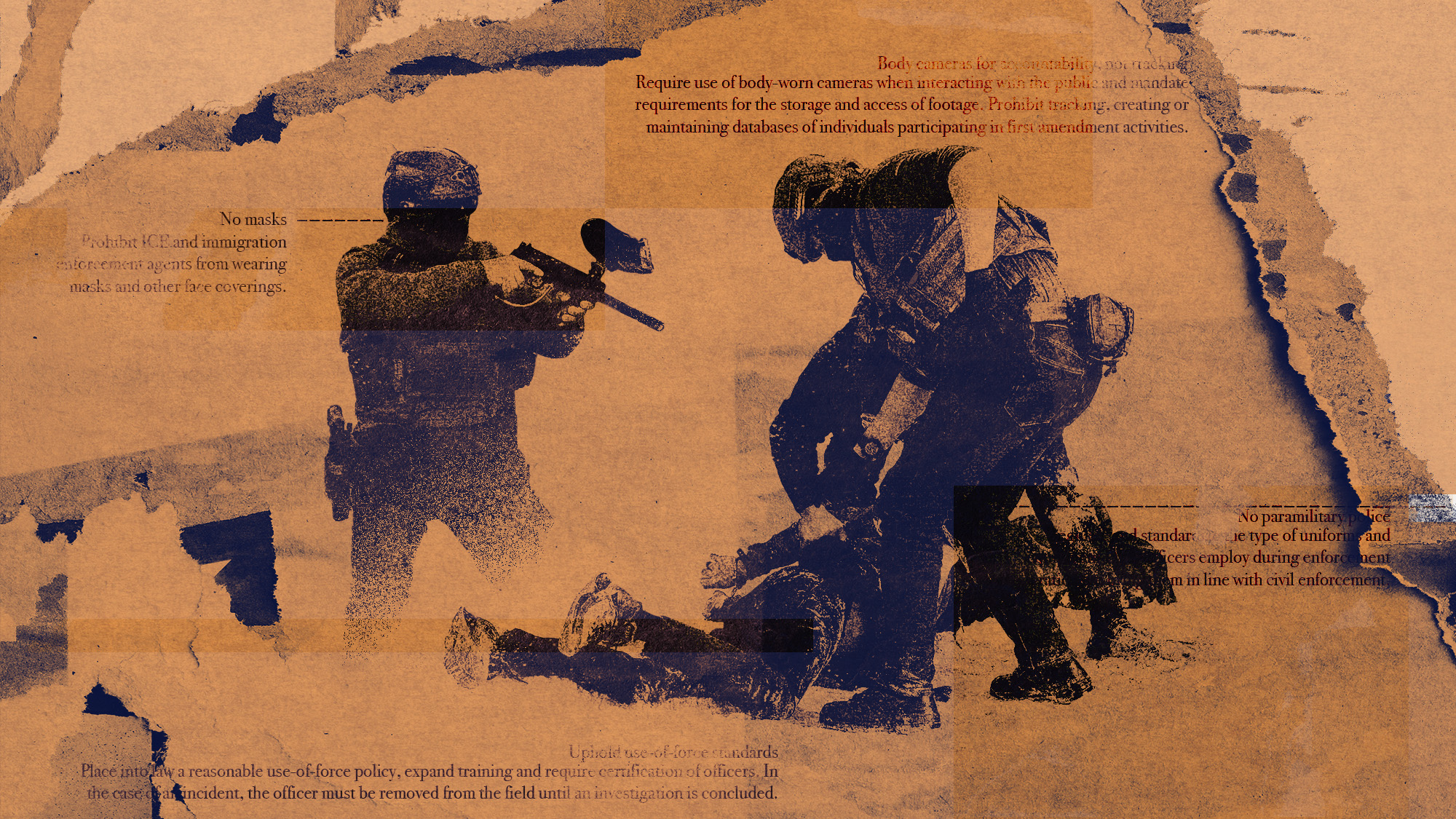

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Japan’s Takaichi cements power with snap election win

Japan’s Takaichi cements power with snap election winSpeed Read President Donald Trump congratulated the conservative prime minister

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax