Is it time the world re-evaluated the rules on migration?

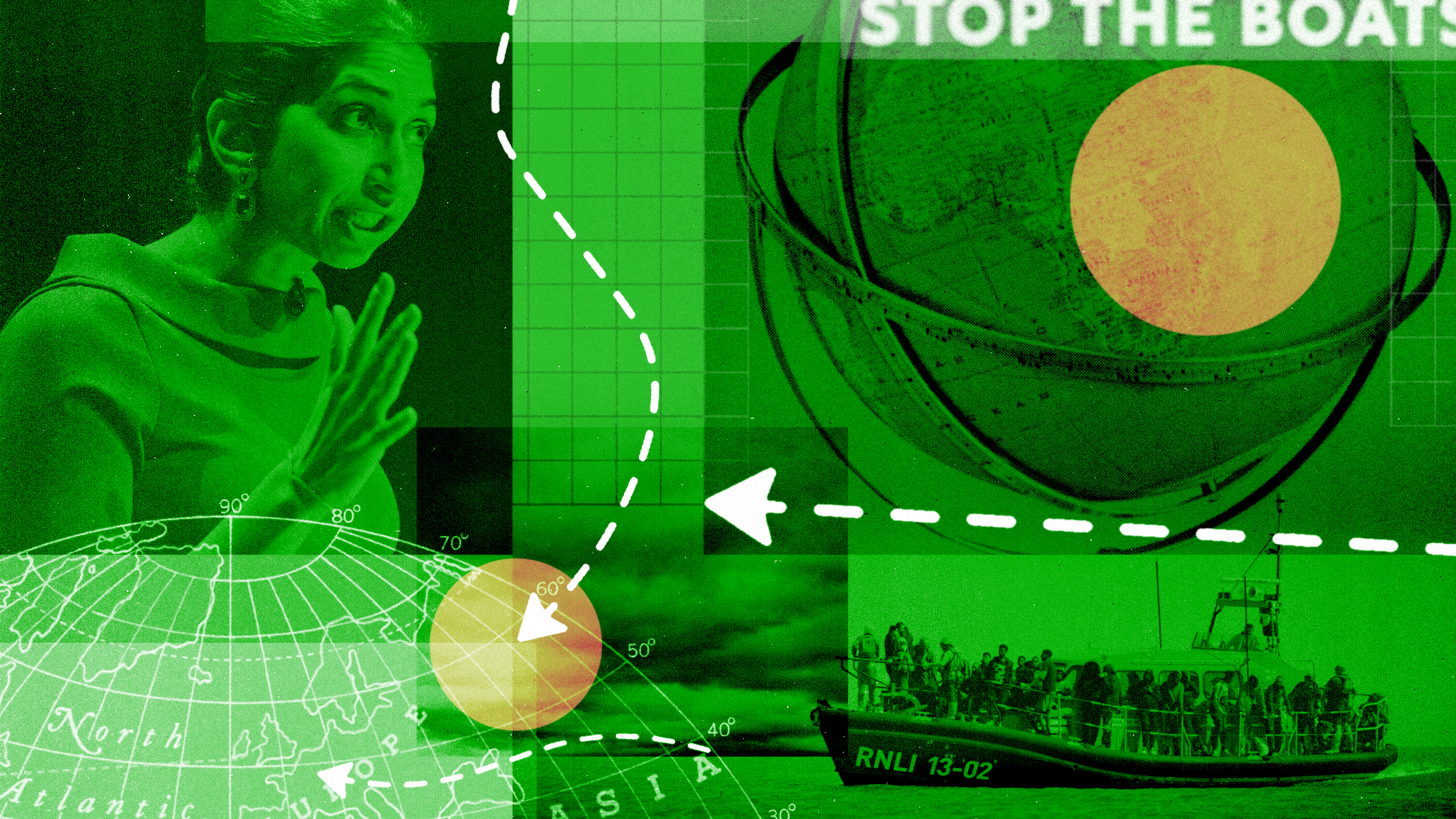

Home Secretary Suella Braverman questions whether 1951 UN Refugee Convention is 'fit for our modern age'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Suella Braverman will call for a fundamental rewrite of the international rules governing refugees, questioning whether the UN's landmark 1951 Refugee Convention is "fit for our modern age".

The home secretary is giving a speech at a right-wing Washington DC think tank, the American Enterprise Institute, in which she will concede that the convention was an "incredible achievement" when it was signed after the Second World War, but that it has since created "huge incentives for illegal migration".

It has led to a situation that is both "absurd and unsustainable", she will say. The legal threshold for granting protection has shifted from "persecuted" towards "something more akin to a definition of 'discrimination'", leading to increased numbers being defined as refugees.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"We will not be able to sustain an asylum system if in effect simply being gay, or a woman, and fearful of discrimination in your country of origin is sufficient to qualify for protection," Braverman will say.

Her comments were also in stark contrast with those of Pope Francis, who said at a meeting in Marseille over the weekend that migration was not an emergency but rather "a reality of our times", said the BBC. He told the audience, which included French president Emmanuel Macron, that the situation "must be governed with wise foresight, including a European response".

What did the papers say?

Braverman's speech is expected to reveal "further detail of Rishi Sunak's ambition to put Britain at the forefront of attempts to reset international structures for tackling ever-growing migration across the world", said The Times.

It comes in the context of the UK's mounting small boats crisis and the government's attempts to circumvent the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), which blocked plans to deport migrants to Rwanda.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the remarks put her on a "collision course" with the UN High Commission for Refugees, which supported the ECHR legal challenge against the government, said The Telegraph. Braverman has "previously signalled her desire to quit [the ECHR] for the way 'politicised' and 'interventionist' judges have trampled on 'the territory of national sovereignty'". However, until now, "she has not publicly and directly taken aim at the [UN] Refugee Convention".

Her reported comments have been widely condemned by refugee charities. The Guardian said that Braverman has "drawn fire" for suggesting Britain should not grant asylum to people who are simply fearful of persecution for being gay.

But this is the "towering challenge confronting the continent", said Gavin Mortimer in The Spectator: "how to distinguish between those fleeing war and persecution, and those who simply see Europe as a way of making money, legally or illegally. Or worse, those who see it as a target."

Braverman is in the US where "just as in Britain and Europe, migration is a bitterly divisive issue", said Sky News's US correspondent Mark Stone. America's southern border is a "perfect example of an asylum system that is neither firm nor fair", he added. "On that, she will find common ground with Britain's own system."

What next?

Labour's shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper has argued that by undermining international agreements Braverman makes it harder to coordinate migrant action alongside other countries.

Critics, however, point to the EU. According to the European Union Agency for Asylum, in 2021 only 34% of applications for protection in the bloc were successful. However, the European Commission said that about 80% of unsuccessful asylum seekers remain where they are, mostly because their home countries or the country from which they travelled to the EU refuse to take them back.

Given this reality, "many EU member states now prefer to reinforce their border protection to make it more difficult for anyone to enter irregularly and to apply for asylum in the first place", wrote Friedrich Püttmann, a PhD candidate at LSE's European Institute, in an article for LSE.

"The liberal reflex is to criticise such EU member states for their repressive border regimes," he concluded. However, "given that a majority of the European public wants less immigration, and that returning rejected asylum seekers is evidently difficult, there is a natural incentive for governments to act in this way".

But "between the hard line and the compassion is a reality", said Sky News' Stone. "This is a time of unprecedented migration. The movement we are seeing represents a new normal that is testing open societies globally."

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire