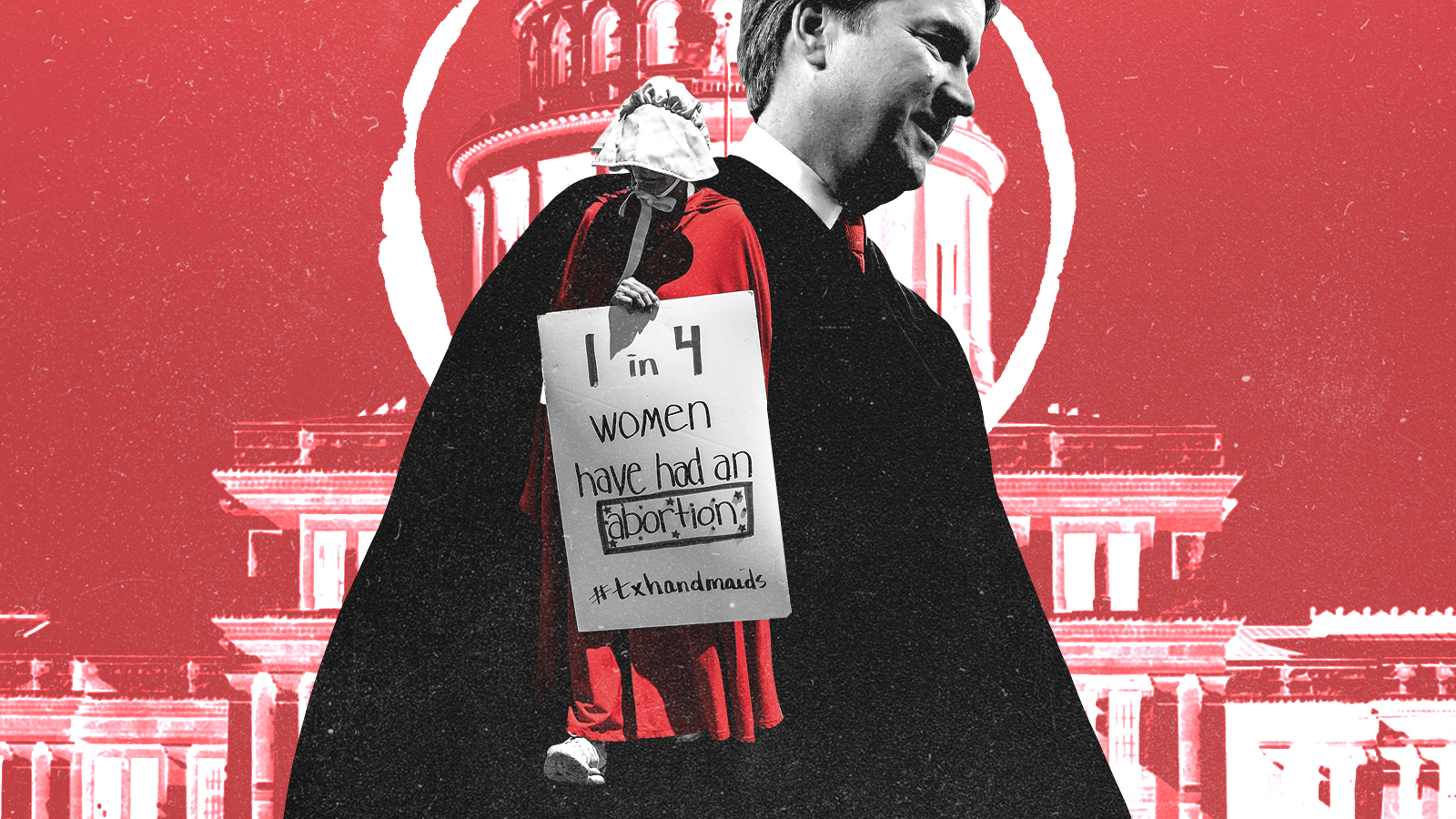

The Texas debacle reveals the perverse consequences of judicializing abortion

This is what happens when legislatures are rendered powerless by the courts

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Just when you thought the political climate couldn't get any hotter, it did. In a decision issued just before midnight on Wednesday, the Supreme Court refused to prevent a so-called Heartbeat Law that would practically ban abortions after the 6th week of pregancy from taking effect. The Texas measure is among the most significant restrictions that any state has imposed since Roe v. Wade established a constitutional right to abortion in 1973.

It's a bad law that establishes a dangerous precedent for private enforcement of public purposes. The solution isn't to strike it down, but to let states where majorities oppose abortion to legislate directly against it.

Start with the law itself. Rather than imposing criminal penalties for performing abortions, the Texas legislature enabled citizens to seek damages from anyone engaged in these activities. The privatized enforcement mechanism allowed Texas' lawyers to argue that opponents had no standing to challenge it, since they were not facing prosecution and have yet not been sued.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

By a 5-4 margin, the Court agreed. Its decision is not a judgment of the law's constitutional merits, but a conclusion that challenges didn't meet the relevant procedural standard to be considered. Rather than settling the matter, the Court opened the door to further litigation.

That litigation could limit or overturn the Texas law at some point in the future. But critics are right that this is a crazy and dangerous way to deal with a serious issue. The problem isn't just the enforcement mechanism, which effectively deputizes the whole population of Texas. Nor is it the sweeping character of the law, which subjects anyone who assists in procuring an abortion — theoretically including a taxi driver who drops off a woman at the clinic — to civil penalties. It's the fact that the statute was designed for the purpose of evading intervention by the federal courts.

Blame for this dodge isn't limited to the Texas legislature or lawyers who designed its strategy. It's a consequence of the Court's decision in Roe (and its affirmation in Casey v. Planned Parenthood). The Court's majority was unable to find a right to abortion in the text of the Constitution. Instead, it relied on the idea that certain rights are implied even if not explicitly mentioned. In addition to concluding that abortion before viability was protected by the 14th Amendment, the Court found that it fell under a right to privacy affirmed by an earlier decision about contraception in Griswold v. Connecticut.

Supporters of the decision point out that the Roe majority did not invent this kind of "penumbral" reasoning and permits states to impose a range of restrictions on abortion. But these arguments reflect rather than resolve the underlying problem. The question isn't only under what conditions abortion should be permitted. It is who decides. By shifting authority from legislatures to the courts, Roe transformed a moral and political disagreement into a judicial one.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The judicialization of abortion has perverse consequences. One is that it's a distraction from the real issue. Few Americans care about rival schools of interpretation or disputes about standing. They care about whether abortion kills babies and if that can ever be justified. Because judges are the arbiters of any restrictions, though, enormous resources are devoted to the minute scrutiny of irrelevant technicalities. That's good news for legal analysts on TV, but it benefits no one else.

That misdirection also undermines courts themselves. The absurdity of Wednesday's decision is that its procedural arguments avoid the purpose of the law. At minimum, as Justice Sotomayor points out, the majority of the Court is complicit in a transparent effort to delay review of a constitutionally-dubious statute. This sort of behavior justifies suspicion that jurisprudence is no more than partisan politics in another guise. Although he offers different formal reasons, that concern helps explain why Chief Justice Roberts, who is extremely attentive to the Court's reputation, joined the dissenters.

Maybe the worst consequences of judicialization, though, are the bad incentives it offers to elected officials. Because they do not have to take responsibility for abortion policy, they are liberated to take positions that please activists and donors while alienating majorities of voters. For Democrats, that means rejecting popular restrictions on the grounds that courts will find them inconsistent with Roe. For Republicans, it means supporting unpopular measures for the same reason.

In that sense, Roe is a permanent source of fuel for the culture war. By elevating a controversial issue to national attention while depriving legislative institutions of the power to do much about it, it rewards rhetorical posturing, symbolic legislation, and false expectations. It's politics as theater rather than genuine deliberation.

Abortion advocates might argue that the problem would go away if Americans accepted that the question was settled in 1973. The late Sen. Arlen Specter offered a version of that argument in Roberts' 2005 confirmation hearings, when he asked whether the nominee considered Roe a "superprecedent." But the idea that a particular decision can never be questioned, revised, or overturned is bizarre. The final word on recurring constitutional disputes is the amendment process, not a majority opinion.

For these reasons, I hope that the Court takes its upcoming chance to reject Roe. Rather than "banning" abortion, as often claimed, that outcome would return authority to do so to legislatures. In this scenario, legislative majorities Texas or other states that have talked for years of prohibiting abortion could dispense with judicial gamesmanship and pursue their real goal.

Overturning Roe is a long-held dream of the pro-life movement. But abortion opponents should be careful what they wish for. There's considerable variation in opinion among different states. The result would likely be a range of outcomes, ranging from outright bans in a few states, to strict requirements after the first trimester in others, to virtually unrestricted abortion elsewhere. Some states might even experiment with de facto local control. Given the larger populations of more liberal jurisdictions, there's a chance that overturning Roe could lead to fewer restrictions for more Americans. States would also have to address health and enforcement challenges that could turn their voters against the toughest rules.

For advocates of abortion rights, on the other hand, overturning Roe offers an opportunity to re-engage with electoral and legislative politics. Although it provided a policy victory, judicial success transformed abortion liberalization into a defensive, elite-focused movement. Over the last half-century years, by contrast, pro-lifers developed an extraordinary network of genuine activists that not only sustained its explicit cause (despite predictions that the issue would phase), but also provided crucial support to the Republican Party.

Would overturning Roe make our civic life even more messy and contentious? In some ways, it probably would. Another way of looking at it, though, is that returning abortion to the legislative process would give citizens more influence. Rather than pleading for the favor of five robed lords, we'd have to turn to people we directly choose to represent us. That's what we call democracy.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.