Succumbing to Putin's blackmail

The U.S. and NATO are still reluctant to give Ukraine what it needs to win

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

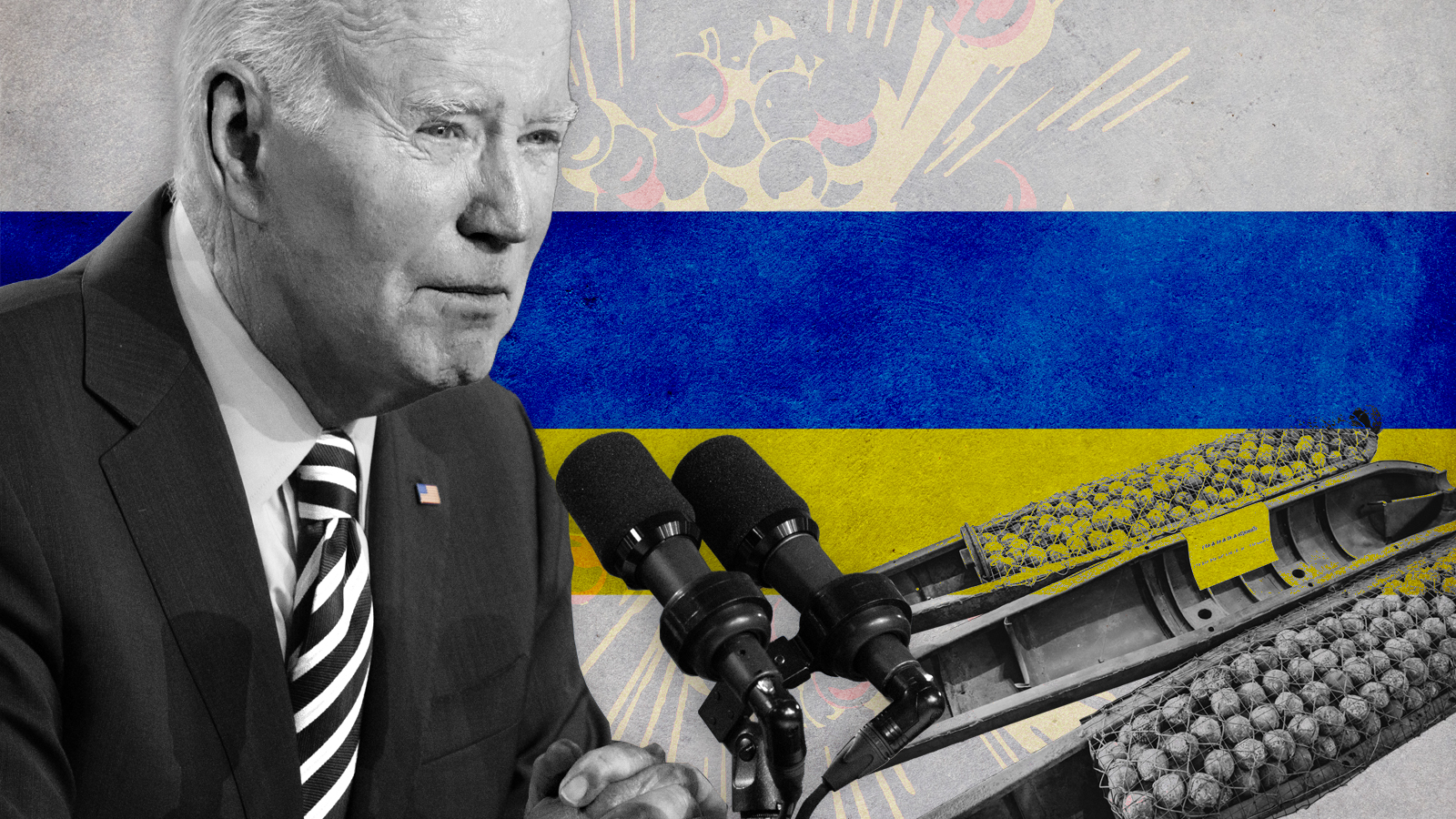

In its second year fighting for its survival, Ukraine says it urgently needs advanced fighter jets and longer-range missiles to repel Russia's invaders from its soil. But President Biden insists that Ukraine "doesn't need F-16s now," and he's resisting sending 190-mile range ATACMS missiles that could strike deep into Russian-held territory. Various rationales are offered, but the unstated reason for Biden's reluctance to provide more advanced weaponry is not hard to discern: He and NATO allies still worry that if Putin is faced with total, humiliating defeat, he might make good on his threat to use battlefield nuclear weapons. The reluctance to give Ukraine's valiant military what it truly needs raises a crucial question, says Julia Ioffe in Puck: Do the U.S. and NATO truly "want Ukraine to win on Ukraine's terms" — driving the Russians out of their country — or to settle for another year or two of bloody stalemate?

With spring offensives looming, the war has become a test of which side can better endure grotesque, World War I–level carnage. "The problem is that the United States gives Ukraine enough to push the Russians back, but not enough to win," said Angela E. Stent, a Russian scholar at Georgetown University. Having suffered 100,000 battlefield casualties and inflicted 200,000 on Russia, Ukraine is running out of soldiers and ammunition. Putin's missile attacks continue to kill and terrorize civilians; much of Ukraine is a hellscape of rubble, craters, and fresh graves. If nuclear blackmail enables Putin to keep what he has seized by force, the message will be heard clearly in Beijing, Pyongyang, and Tehran. A Chinese invasion of Taiwan becomes more likely. Violating the nuclear taboo would be suicidal for Putin; for the West, the greater risk is submitting to his blackmail. Driving the war criminals out of Ukraine is not only a moral imperative — it's clearly in the best interests of the U.S., Europe, and the free world.

This is the editor's letter in the current issue of The Week magazine.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

William Falk is editor-in-chief of The Week, and has held that role since the magazine's first issue in 2001. He has previously been a reporter, columnist, and editor at the Gannett Westchester Newspapers and at Newsday, where he was part of two reporting teams that won Pulitzer Prizes.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Russia's Crimea fleet shipyard on fire after Ukrainian missile strike

Russia's Crimea fleet shipyard on fire after Ukrainian missile strikePhotos and videos showed huge explosions and raging fires at the Sevastopol Shipyard

-

Has Ukraine's counteroffensive become a 'war of attrition?'

Has Ukraine's counteroffensive become a 'war of attrition?'Today's Big Question An expected thrust has turned into a slog

-

Saudi Arabia to host Russia-less Ukraine peace talks, Kyiv confirms, as Moscow hit by more drones

Saudi Arabia to host Russia-less Ukraine peace talks, Kyiv confirms, as Moscow hit by more dronesSpeed Read

-

Attack attributed to Ukraine naval drones damages key Russian bridge to occupied Crimea

Attack attributed to Ukraine naval drones damages key Russian bridge to occupied CrimeaSpeed Read

-

Inside Russia's war crimes

Inside Russia's war crimesSpeed Read Occupying forces in Ukraine are accused of horrific atrocities. Can they be held accountable?

-

Top Russian generals killed, fired, disappeared after aborted Wagner mutiny

Top Russian generals killed, fired, disappeared after aborted Wagner mutinySpeed Read

-

Should Ukraine be admitted to NATO?

Should Ukraine be admitted to NATO?Talking Point With this week's Vilnius summit, Ukraine's possible accession to the military alliance is more than a little top of mind

-

Why are cluster munitions controversial?

Why are cluster munitions controversial?Today's Big Question The U.S. will send a new weapon to Ukraine. Human rights advocates are alarmed.