Why India's medical schools are running low on bodies

A shortage of cadavers to train doctors on is forcing institutions to go digital

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Medical students in India are missing out on a crucial rite of passage because of a lack of dead bodies, or cadavers, for them to learn from.

Logistical issues and cultural sensitivities mean the world's "most populous country" is "running low on bodies", said The Independent, forcing medical schools to adopt anatomical models or digital simulations for training instead.

A complex interplay

Cadaver dissection is "a must" for first-year medical students, Dr Kumari T K, a professor with the Department of Anatomy at Azeezia Medical College in Kollam, told the New Indian Express (NIE), because medicine and anatomy "cannot be learnt through theories".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But instead of the required rate of one cadaver for 10 medical students, India is thought only to have one cadaver for every 50 students in some colleges.

Reasons for the shortage include "cultural, religious and logistical hurdles" and a "lack of awareness", experts told The Independent. Beliefs around death and the afterlife "complicate the picture" because many families want to perform religious rites soon after death and fear that donating the body to science would delay both that and a sense of closure as they grieve.

Even when the deceased person wished to donate his or her body to medical science, the family sometimes "gives more priority to the emotional aspect", Rejeesh Rehman told NIE. He donated the body of his father for medical studies but said many other families prefer to organise their relative's funeral in line with "religious beliefs" and therefore "may not allow to donate the body".

This cadaver shortage is not limited to India. The Times reported in March that, "faced with a dwindling supply of fresh bodies to train on", British medical schools were resorting to dealing with the US, where cadavers can be "supplied for profit by anyone", regardless of training or expertise, without any federal laws being broken.

No substitute

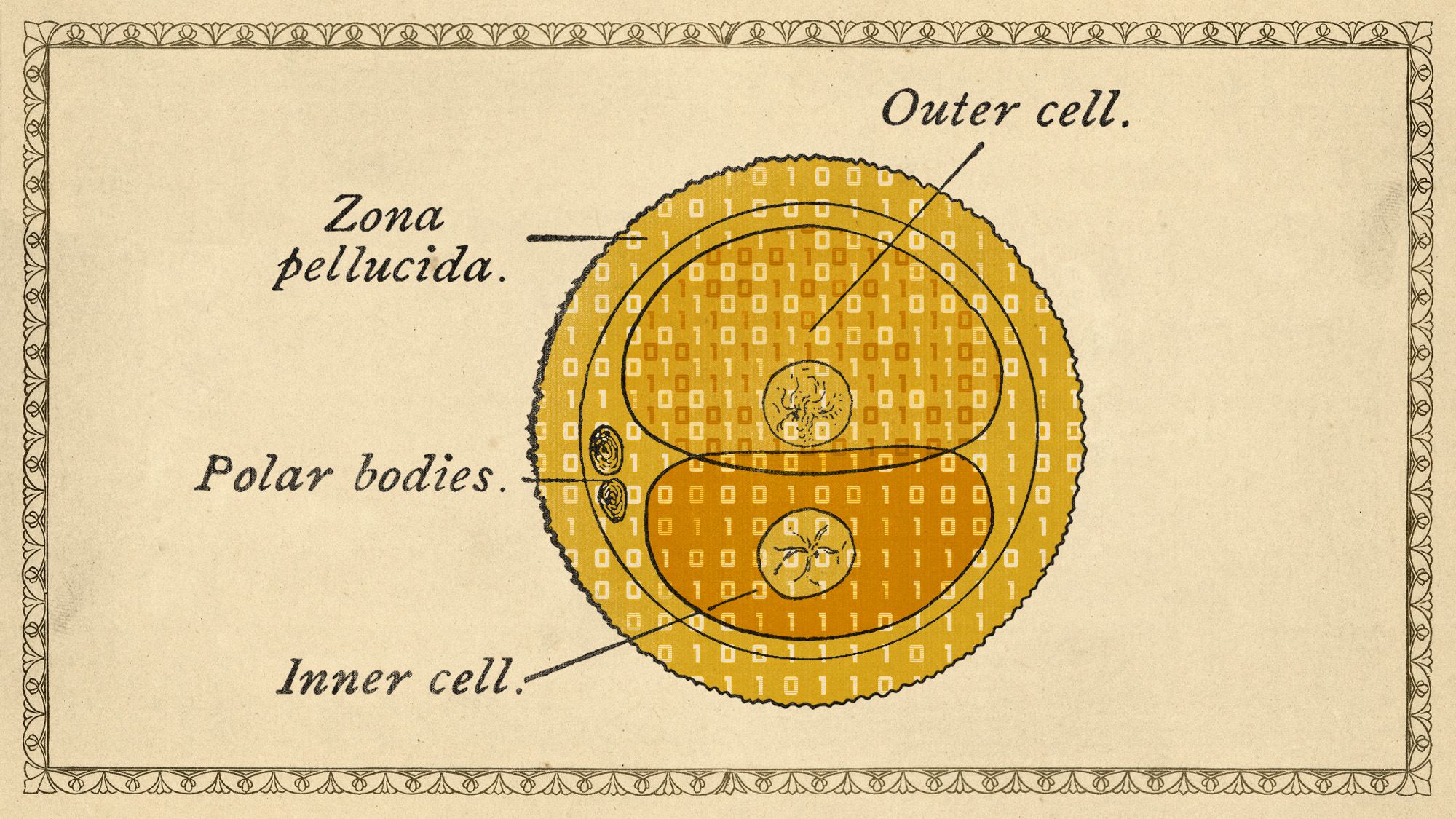

Medical schools the world over have, for the past 10 years, been experimenting with ways of teaching anatomy without a body, replacing real cadavers with virtual ones. And the Covid pandemic meant many schools had no choice but to use them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Physical cadaver labs are expensive to run, radiology professor Mark Griswold of Case Western Reserve University, Ohio, told Slate. It can also be difficult to see some anatomy, such as lymph nodes, the pancreas, and some blood vessels on a physical cadaver. The use of virtual cadavers "standardises the process", added Marc J Khan, the dean of Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at the University of Nevada, meaning all students are working with the same type of 'body'.

But the virtual experience isn't the same, anatomist and cadaver-donation advocate Dr Vaishaly Bharambe told The Independent. Although they provide a "study in three dimensions", virtual bodies "cannot ever replace the feel of a real human being". And there is no technology “that will allow you to imagine what different organs inside a person feel like".

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Do we need more right-wing scientists?

Do we need more right-wing scientists?Talking Point Academics have a 'responsibility' to demonstrate why research matters to people who are not politically left-leaning, says Wellcome boss

-

Scientists are the latest 'refugees'

Scientists are the latest 'refugees'In the spotlight Brain drain to brain gain

-

Scientists want to create an AI virtual cell

Scientists want to create an AI virtual cellUnder the radar Generative AI could advance medical research

-

Mirror bacteria could pose major health risks

Mirror bacteria could pose major health risksUnder the Radar The experimental research could have dangerous impacts

-

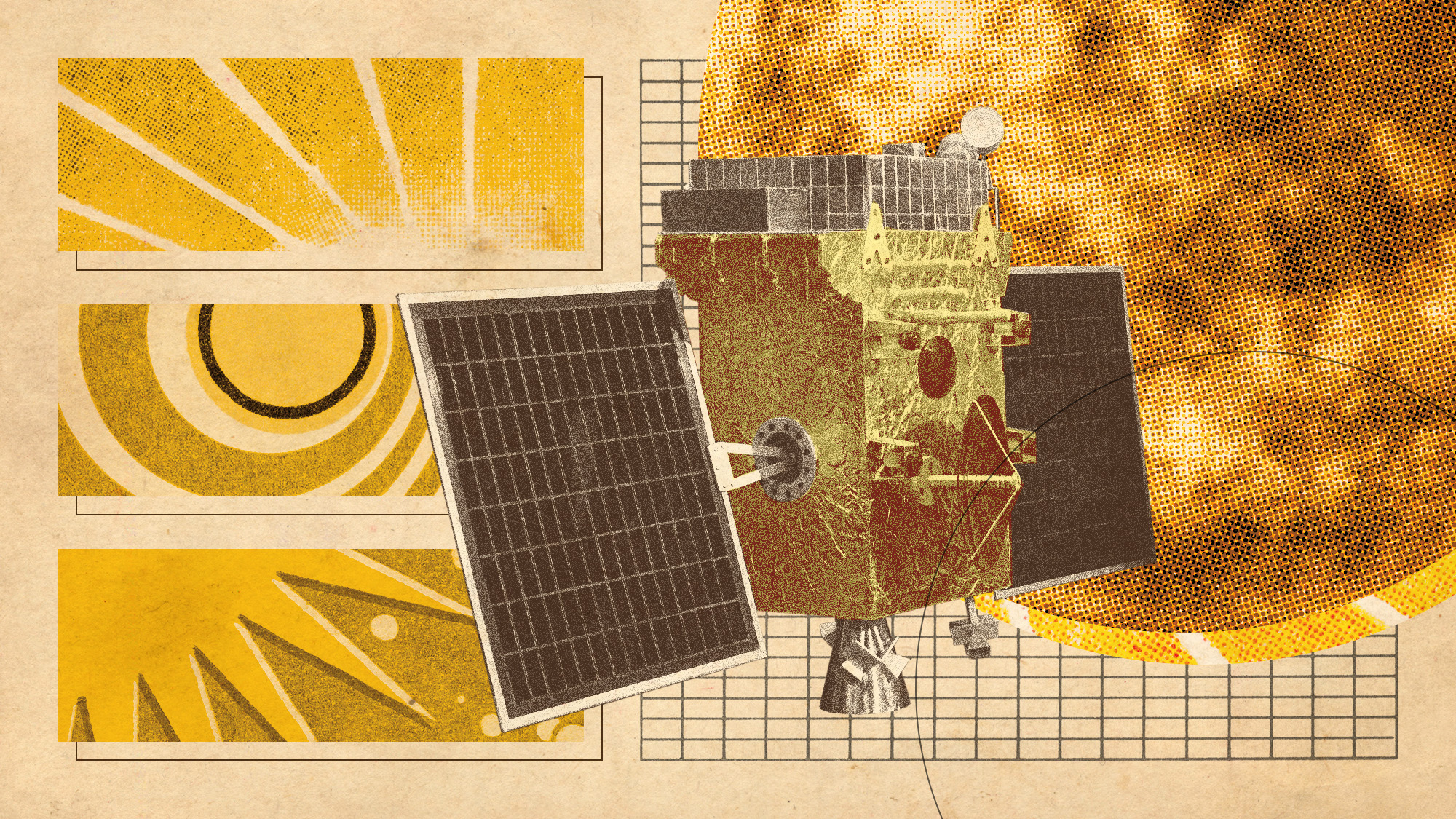

Indian space mission's moment in the Sun

Indian space mission's moment in the SunUnder the Radar Emerging space power's first solar mission could help keep Earth safe from Sun's 'fireballs'