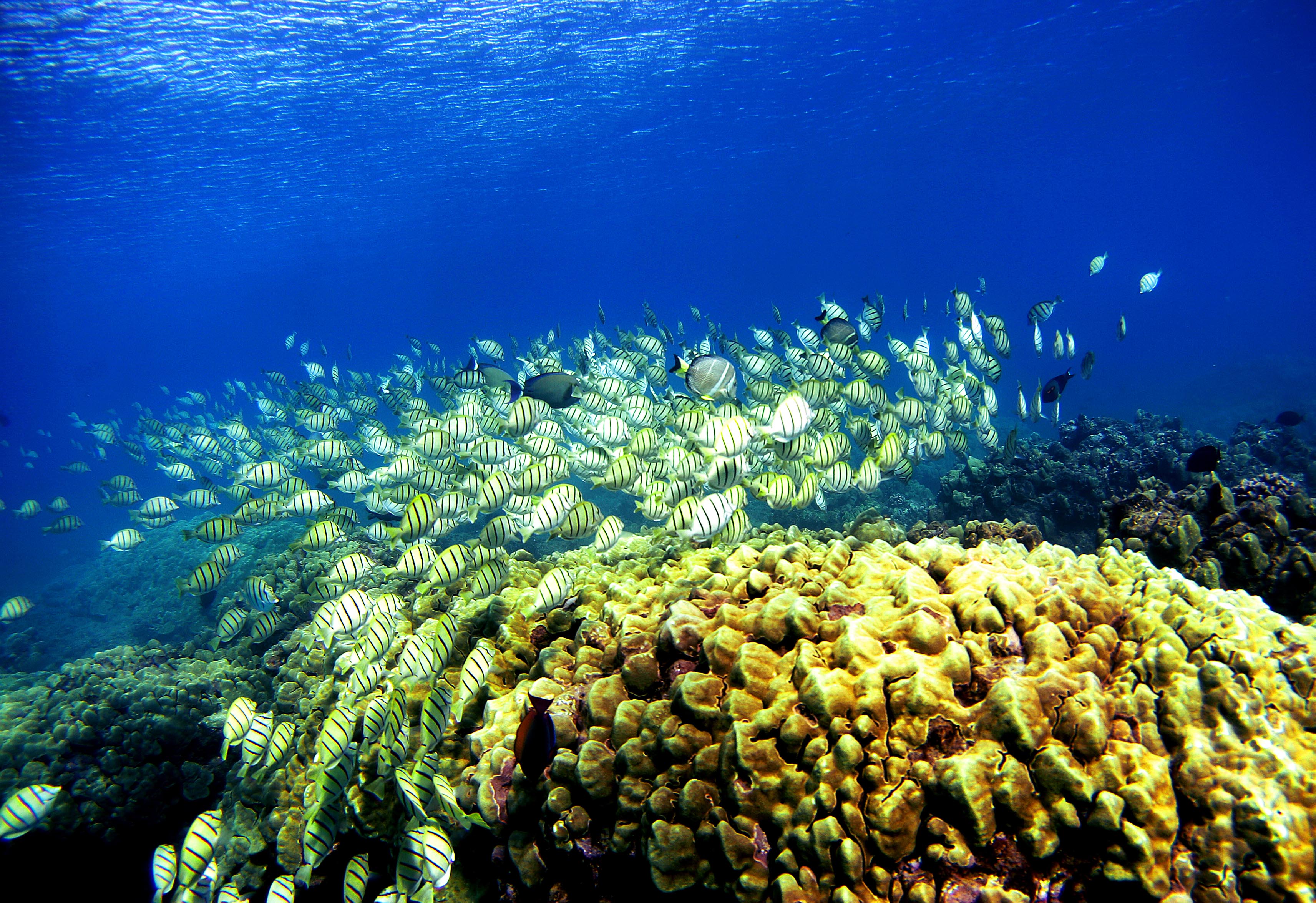

Climate change is harming the Great Barrier Reef faster than expected

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you were planning on visiting the Great Barrier Reef, you might want to get on that soon.

A study published in the journal Nature on Wednesday found that the colorful species of coral that comprise the reef have had a harder time reproducing, thanks to warming ocean waters. After a major "coral bleaching" event in 2017, National Geographic explained, the reproductive ability of the Great Barrier Reef's coral was down by as much as 89 percent. And now, the study's results predict that it could take as long as 10 years for the reef to recover — if not even longer, if more bleaching events occur.

Not only is the coral population receding drastically, but the balance of different coral species is also changing, The Guardian reported. Acropora, the dominant species in the Great Barrier Reef, declined by 93 percent in the last two years. The changing ecosystem means it's likely that the reef will never be the same. "If you change the mix of babies, you change the mix that they grow up to be," explained Terry Hughes, the study's lead author.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"We've always anticipated that climate change would shift the mix of coral," Hughes said, but it's happening at a far faster rate than expected. Read more about the new study at National Geographic.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Shivani is the editorial assistant at TheWeek.com and has previously written for StreetEasy and Mic.com. A graduate of the physics and journalism departments at NYU, Shivani currently lives in Brooklyn and spends free time cooking, watching TV, and taking too many selfies.

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

At least 8 dead in California’s deadliest avalanche

At least 8 dead in California’s deadliest avalancheSpeed Read The avalanche near Lake Tahoe was the deadliest in modern California history and the worst in the US since 1981

-

Death toll from Southeast Asia storms tops 1,000

Death toll from Southeast Asia storms tops 1,000speed read Catastrophic floods and landslides have struck Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia

-

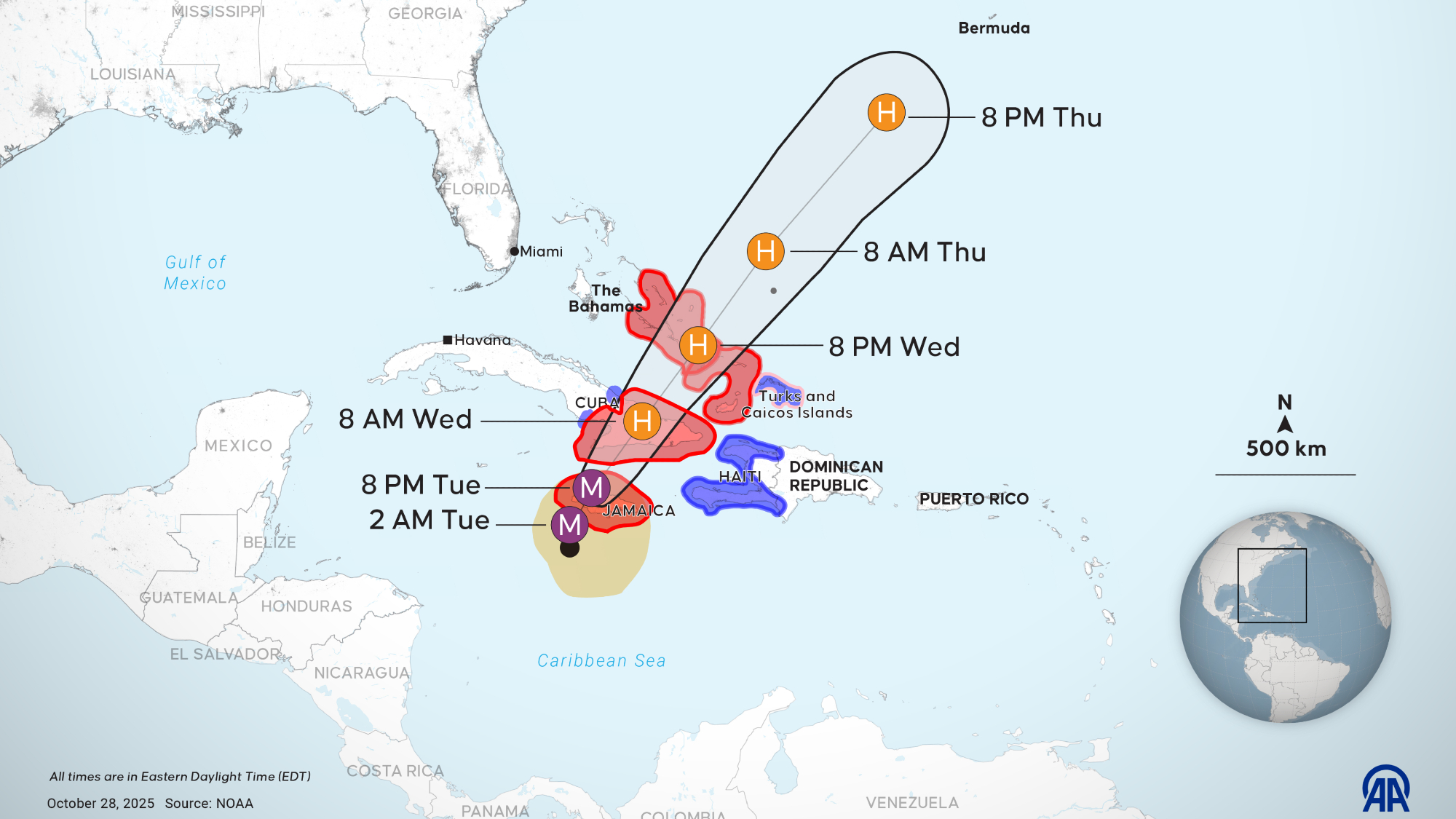

Hurricane Melissa slams Jamaica as Category 5 storm

Hurricane Melissa slams Jamaica as Category 5 stormSpeed Read The year’s most powerful storm is also expected to be the strongest ever recorded in Jamaica

-

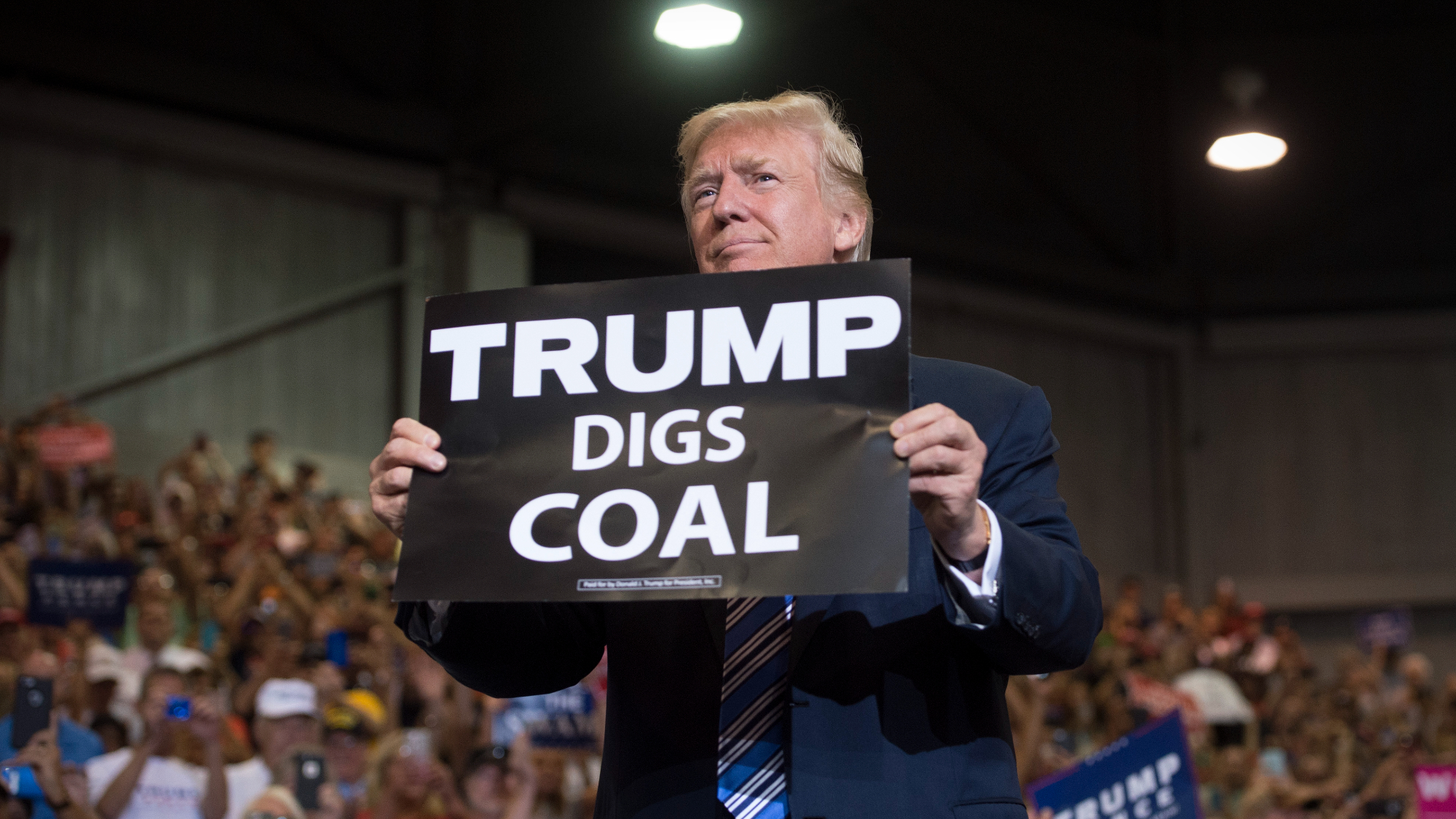

Renewables top coal as Trump seeks reversal

Renewables top coal as Trump seeks reversalSpeed Read For the first time, renewable energy sources generated more power than coal, said a new report

-

China vows first emissions cut, sidelining US

China vows first emissions cut, sidelining USSpeed Read The US, the world’s No. 2 emitter, did not attend the New York summit

-

At least 800 dead in Afghanistan earthquake

At least 800 dead in Afghanistan earthquakespeed read A magnitude 6.0 earthquake hit a mountainous region of eastern Afghanistan

-

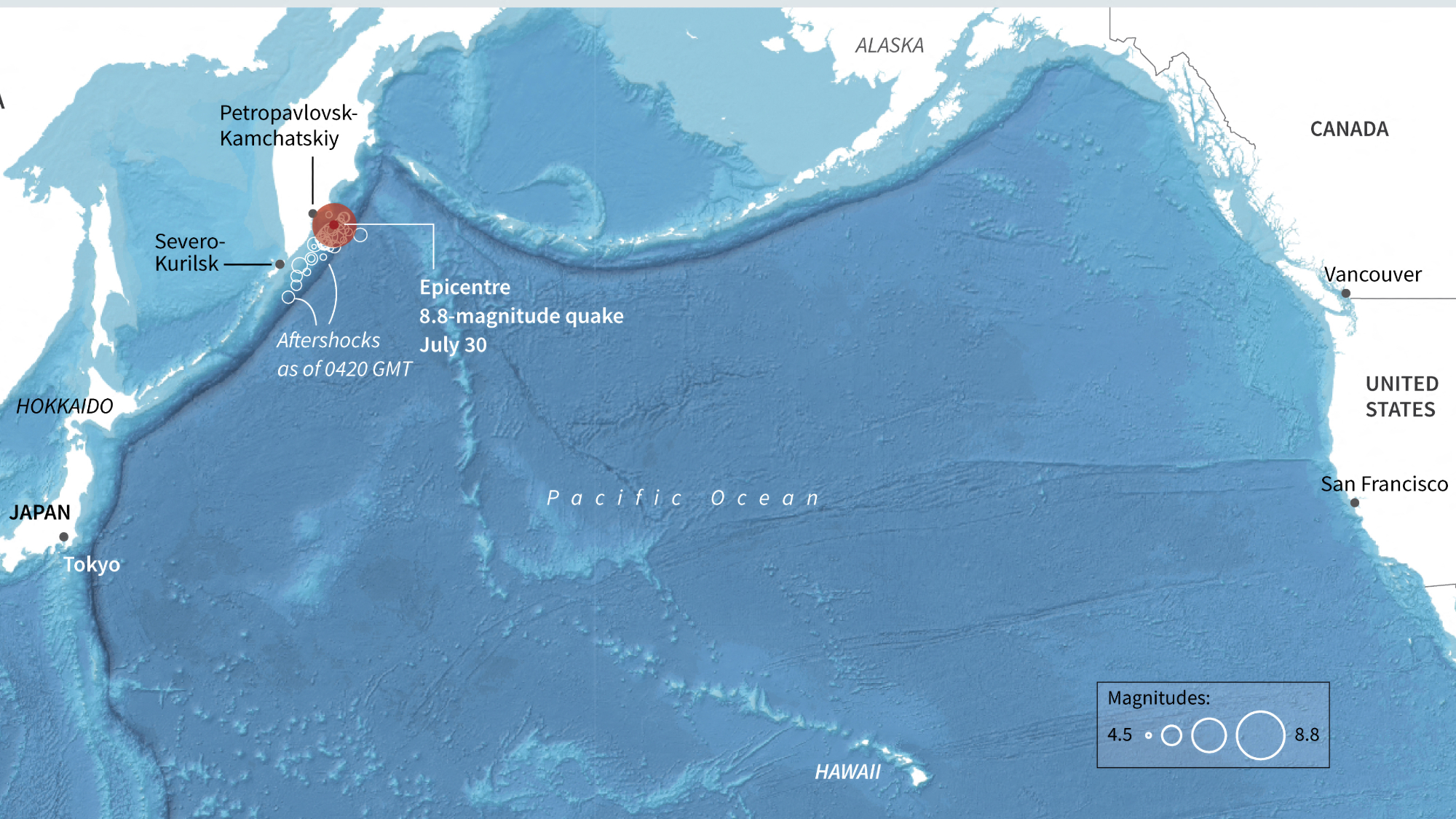

Massive earthquake sends tsunami across Pacific

Massive earthquake sends tsunami across PacificSpeed Read Hundreds of thousands of people in Japan and Hawaii were told to evacuate to higher ground

-

FEMA Urban Search and Rescue chief resigns

FEMA Urban Search and Rescue chief resignsSpeed Read Ken Pagurek has left the organization, citing 'chaos'