John Oliver explains the mess on Mount Everest, offers a fun and easy solution

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"Everest was first summited in 1953 by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay," John Oliver said on Sunday's Last Week Tonight. "Before then it had been seen as almost an impossible feat," which probably explains why "Everest" has "become everyone's go-to metaphor for a significant challenge," warranted or not. Now however, "climbing Everest has become dangerously popular," he said. That means high death tolls and long lines to the summit, tons of trash, and a "fecal time bomb" as human waste melts and slides downhill.

"So tonight, let's look at what is causing these issues, how Everest's climbing industry operates, and how we can potentially make things safer," Oliver said. The first problem is that there is a narrow window in which people can summit Everest, sometimes just a few days, and starting in the 1990s, commercial expeditions became available, sometimes with six-figure luxury packages. Oliver explained the difference between Sherpas and sherpas, and the very dangerous and integral role sherpas play. "Huge risks are being taken by sherpas to give their client the bragging rights of conquering 'the ultimate mountain,'" he said, noting that Everest isn't actually the hardest mountain to climb.

Everest is still deadly to unprepared or inexperienced climbers, there is essentially no gate-keeping at the Nepal end — Tibet is stricter in granting permission — and some climbing outfits let anyone try to summit, Oliver said, citing one specific example. "Even Sir Edmund Hillary was depressed at what he had seen Mount Everest become," he said. "Some of the people climbing Everest aren't doing it out of a passion for mountaineering, but just because they want to say they climbed Everest," because "a selfie from the summit of Makalu" won't "get Everest levels of Instagram love." But Oliver had a solution, plus a few interludes from sherpa Rick Astley and some NSFW language. Watch below. Peter Weber

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

‘One Battle After Another’ wins Critics Choice honors

‘One Battle After Another’ wins Critics Choice honorsSpeed Read Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, which stars Leonardo DiCaprio, won best picture at the 31st Critics Choice Awards

-

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper bus

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper busThe Week Recommends Overnight service with stops across Switzerland and the Netherlands promises a comfortable no-fly adventure

-

Son arrested over killing of Rob and Michele Reiner

Son arrested over killing of Rob and Michele ReinerSpeed Read Nick, the 32-year-old son of Hollywood director Rob Reiner, has been booked for the murder of his parents

-

Rob Reiner, wife dead in ‘apparent homicide’

Rob Reiner, wife dead in ‘apparent homicide’speed read The Reiners, found in their Los Angeles home, ‘had injuries consistent with being stabbed’

-

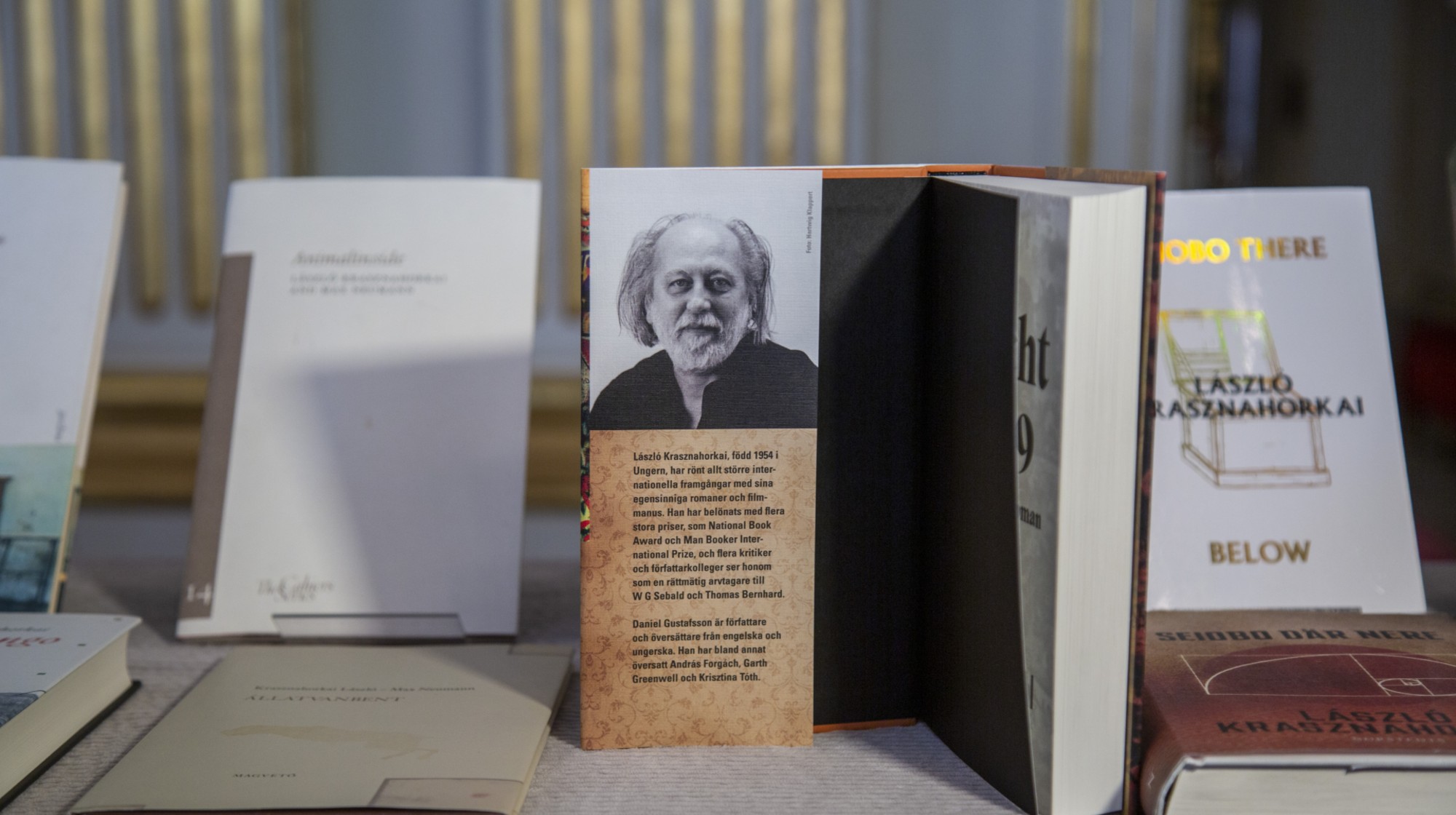

Hungary’s Krasznahorkai wins Nobel for literature

Hungary’s Krasznahorkai wins Nobel for literatureSpeed Read László Krasznahorkai is the author of acclaimed novels like ‘The Melancholy of Resistance’ and ‘Satantango’

-

Primatologist Jane Goodall dies at 91

Primatologist Jane Goodall dies at 91Speed Read She rose to fame following her groundbreaking field research with chimpanzees

-

Florida erases rainbow crosswalk at Pulse nightclub

Florida erases rainbow crosswalk at Pulse nightclubSpeed Read The colorful crosswalk was outside the former LGBTQ nightclub where 49 people were killed in a 2016 shooting

-

Trump says Smithsonian too focused on slavery's ills

Trump says Smithsonian too focused on slavery's illsSpeed Read The president would prefer the museum to highlight 'success,' 'brightness' and 'the future'