The technohorror genre grows up

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fear — they say — is a response elicited by things we don't understand. We're afraid of flying, because we don't grasp aerodynamics. We're afraid of the spider in our bathtub, because we don't know if it's a species that can hurt us. We're afraid of computers, because, who knows? Maybe one day they'll have a mind of their own.

Decades ago, the latter bloomed into a full-fledged subgenre of horror preoccupied with contemporary anxieties of isolation and alienation, accelerated by advances in technology. "Technohorror is not merely a form of pure technophobia, but instead is a form of creeping, pervasive dread born of symbiotic uncertainty in our relationship to technology and our shifting perceptions of what it means to be human," explains Daniel W. Powell in his book, Horror Culture in the New Millennium.

But while technohorror began as a genre obsessed with the perils of digital life (think of the dated hysteria of 1992's Lawnmower Man, or 1995's The Net, or 2002's Feardotcom), movies like Jane Schoenbrun's terrific narrative feature debut, We're All Going to the World's Fair, are blazing a new path forward — one that stems from a deep understanding of technology, rather than ignorance and fear of it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We're All Going to the World's Fair premiered this week as part of the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, and introduces us to Casey (Anna Cobb, in her fantastic feature debut), a high schooler who decides to join the "World's Fair" challenge. Sitting before her computer screen — our frame into the scene — Casey pricks her finger and chants "I want to go to the World's Fair" three times, then watches a strobing video that's supposed to, in some ominous way, transform her. She proceeds to record video diaries about her experiences as the challenge progresses; they're never watched by more than a handful of people, but still manage to catch the attention and concern of a fellow World's Fair obsessive who goes by the anonymous initials JLB.

While traditional technohorror uses an outside-in perspective to evaluate digital life — whether Nightmare Weekend or Kairo or Stephen King's exceptionally dreadful novel Cell — We're All Going to the World's Fair is a creation of the inside out. That means more than just that Schoenbrun (who wrote, directed, and edited the film) has a vocabulary that includes "creepypasta." Rather, like several other recent movies (Unfriended: Dark Web and Cam being other greats of this new generation), World's Fair truly "gets" how people use the internet to forge their identities, reach out for connection, and play-act different versions of themselves.

The creeping sense of dread stems not from an alarmist fear of what a teenage girl finding her way on the internet might do, but knowing exactly. Unlike technohorror of yore, the answer doesn't involve robots bent on world domination, or demons that pass through phone lines, or serial killers lurking on the other side of chatrooms, but the draw of online communities when you have no one in your hometown, and the internet strangers who fill the void of friends.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Is a social media ban for teens the answer?

Is a social media ban for teens the answer?Talking Point Australia is leading the charge in banning social media for people under 16 — but there is lingering doubt as to the efficacy of such laws

-

Why are American conservatives clashing with Pope Leo?

Why are American conservatives clashing with Pope Leo?Talking Points Comments on immigration and abortion draw backlash

-

Questions abound over the FAA’s management of Boeing

Questions abound over the FAA’s management of BoeingTalking Points Some have called the agency’s actions underwhelming

-

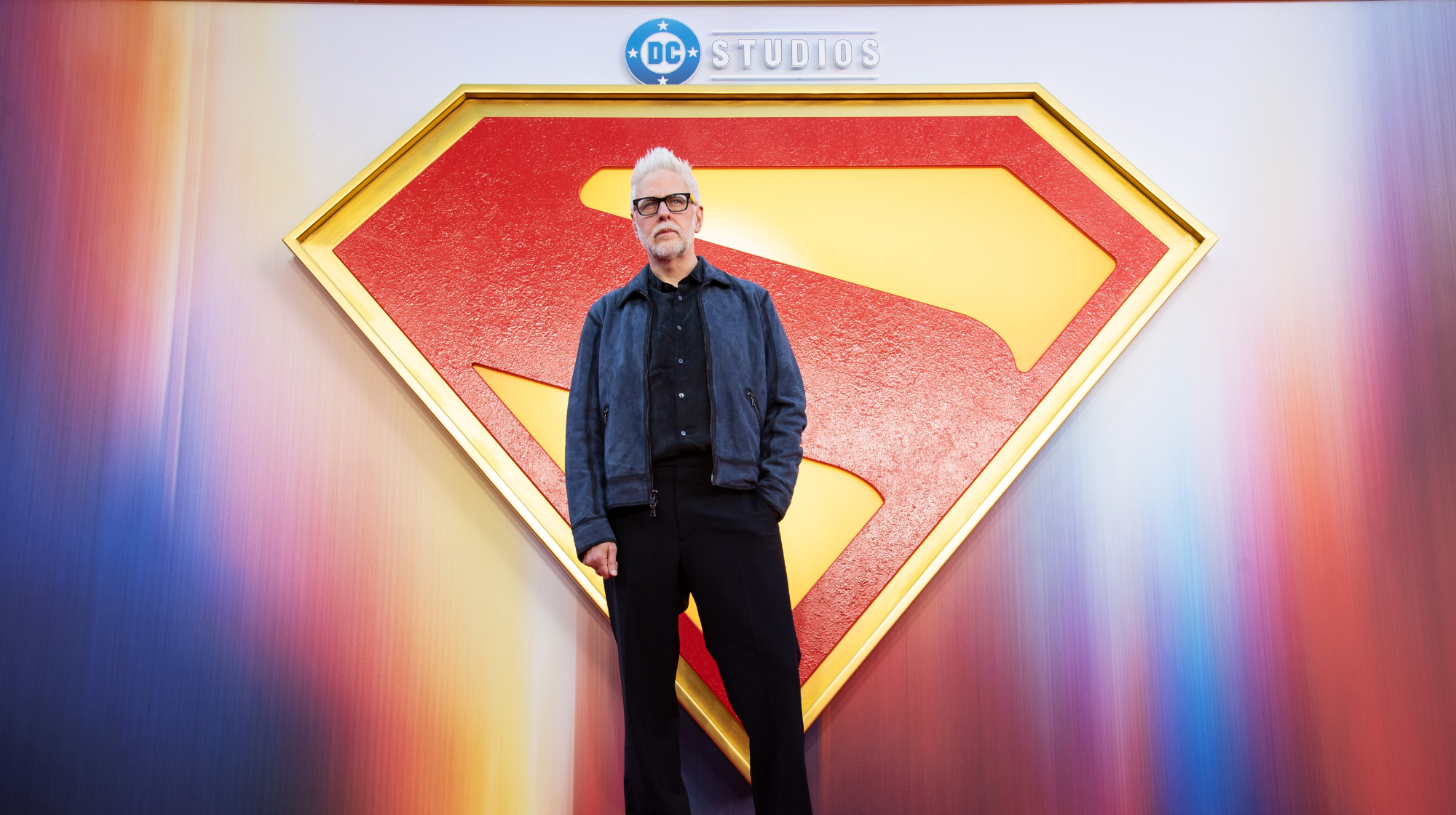

'Immigrant' Superman film raises hackles on the right

'Immigrant' Superman film raises hackles on the rightTALKING POINT Director James Gunn's comments about the iconic superhero's origins and values have rankled conservatives who embrace the Trump administration's strict anti-immigrant agenda

-

Disney is still shielding Americans from an episode of 'Bluey'

Disney is still shielding Americans from an episode of 'Bluey'Talking Points The US culture war collides with a lucrative children's show

-

Jony Ive's iPhone design changed the world. Can he do it again with OpenAI?

Jony Ive's iPhone design changed the world. Can he do it again with OpenAI?Talking Points Ive is joining OpenAI, hoping to create another transformative piece of personal technology. Can lightning strike twice?

-

Is method acting falling out of fashion?

Is method acting falling out of fashion?Talking Points The divisive technique has its detractors, though it has also wrought quite a few Oscar-winning performances

-

Wicked fails to defy gravity

Wicked fails to defy gravityTalking Point Film version of hit stage musical weighed down by 'sense of self-importance'