'De-influencers' are telling TikTok users what not to buy

Burdened by inflation, followers are eager for honest recommendations

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

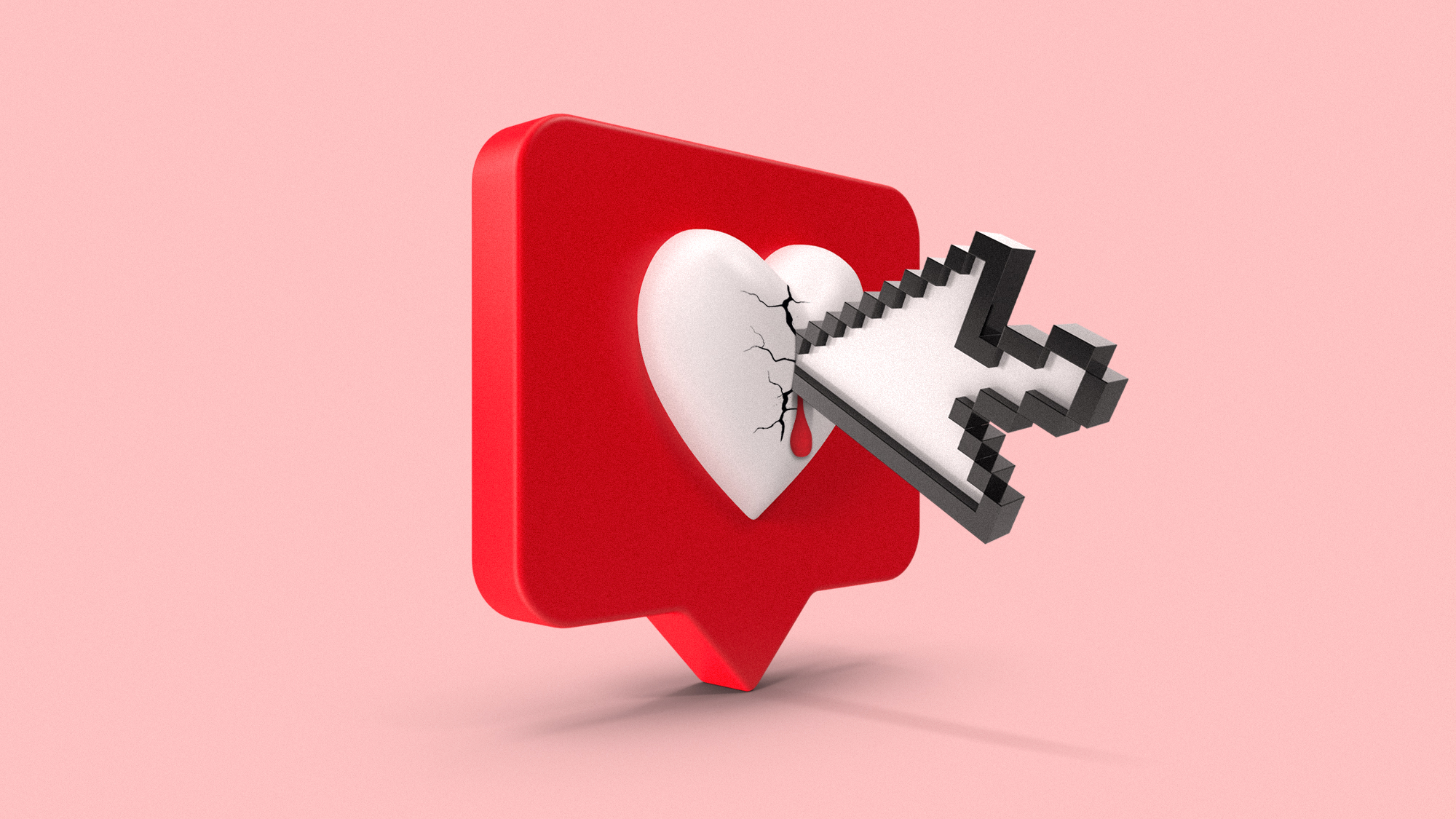

For the past few years, influencer marketing has dramatically shifted how brands connect with consumers. With just one video or post, popular content creators can turn anything from a beauty product to a water bottle into a viral sensation, especially on TikTok. But recently, some content creators have started to take another route, using their platform to tell users what not to buy. They're calling it "de-influencing." Here's everything you need to know:

What is de-influencing?

De-influencing "refers to people speaking critically about products on a platform where endorsements run rampant," The Wall Street Journal explains. De-influencing videos may encourage consumers to consider cheaper alternatives to high-end viral products or "discourage them from spending money in certain categories altogether." Such videos are an antithesis "to a seemingly endless stream of recommendations and promotional content, and "a sign of growing backlash to overconsumption."

The de-influencing trend "is a stark contrast to prior ones like #TikTokMadeMeBuyIt, when consumers were showing off products they purchased after seeing them on the social media app," The Associated Press says. Brands have invested heavily in influencer marketing in recent years, given how effective one viral video can be. Videos tagged with #TikTokMadeMeBuyIt have reached over 40 billion views, while videos with #deinfluencing have garnered over 220 million.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Jenna Drenten, associate professor of marketing at Loyola University Chicago's Quinlan School of Business, told the Journal that initially, "influencers were very beholden to their audience" until brands started to partner with them to leverage their popularity. "Then, influencers became super beholden to brands." The recent rise in de-influencing videos shows that "influencers are swinging back to the accountability between themselves and their audiences," Drenten said.

When did the trend start?

It's not entirely clear how the trend originated, but the Journal says one of the early TikTok videos with the de-influencing hashtag came from beauty influencer Maddie Wells. In 2020, she began discussing products she saw customers frequently return while working at Sephora and Ulta. In one video from September with 2.5 million views, Wells "name-drops the Ordinary's Peeling Solution and Too Faced's Better Than Sex mascara" as cosmetics that were often returned, "despite being frequently touted by beauty influencers," the Journal writes. "I'm calling this 'de-influencing,'" Wells says in the video.

Why is de-influencing so popular now?

Influencers say the trend took off last month, "propelled by macroeconomic stress" and "a long-brewing backlash against pay-to-play product reviews," The Los Angeles Times reports. And a recent scandal wherein a TikTok beauty influencer wore false lashes in a sponsored video meant to promote a L'Oreal mascara "added more fuel to the fire."

"There's a theme of over-consumption when it comes to social media, and I think people are starting to notice just how detrimental it is towards our wallets and the environment," de-influencer Karen Wu said in an email to the Times. "Add in the economic downturn, and … consumers are starting to grow tired of the rhetoric that they NEED every viral product they see."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Theara Coleman has worked as a staff writer at The Week since September 2022. She frequently writes about technology, education, literature and general news. She was previously a contributing writer and assistant editor at Honeysuckle Magazine, where she covered racial politics and cannabis industry news.

-

What to watch out for at the Winter Olympics

What to watch out for at the Winter OlympicsThe Explainer Family dynasties, Ice agents and unlikely heroes are expected at the tournament

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?Talking Point The latest slew of embarrassing emails from Fergie to the notorious sex offender have put her daughters in a deeply uncomfortable position

-

TikTok finalizes deal creating US version

TikTok finalizes deal creating US versionSpeed Read The deal comes after tense back-and-forth negotiations

-

Is social media over?

Is social media over?Today’s Big Question We may look back on 2025 as the moment social media jumped the shark

-

Sora 2 and the fear of an AI video future

Sora 2 and the fear of an AI video futureIn the Spotlight Cutting-edge video-creation app shares ‘hyperrealistic’ AI content for free

-

Trump allies reportedly poised to buy TikTok

Trump allies reportedly poised to buy TikTokSpeed Read Under the deal, U.S. companies would own about 80% of the company

-

TikTok's fate uncertain as weekend deadline looms

TikTok's fate uncertain as weekend deadline loomsSpeed Read The popular app is set to be banned in the U.S. starting Sunday

-

TikTok alternatives surge in popularity as app ban looms

TikTok alternatives surge in popularity as app ban loomsThe Explainer TikTok might be prohibited from app stores in the United States

-

States sue TikTok over children's mental health

States sue TikTok over children's mental healthSpeed Read The lawsuit was filed by 13 states and Washington, D.C.

-

What happens if TikTok is banned?

What happens if TikTok is banned?Today's Big Question Many are fearful that TikTok's demise could decimate the content creator community