High-handed Erdogan: what lies behind the violence in Turkey

Turkey is officially secular – and the protesters don't like Erdogan's increasingly Islamic agenda

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

THE RIOTING that has gripped Turkey for the past three days seemed to come straight out of the blue. The country had been doing well, personal incomes doubling in the ten-year reign of the current prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, of the moderate Islamic Justice and Development Party, the AKP. By the time the weekend was over, 1,700 people had been arrested for taking part in demonstrations – riots according to the authorities – in 67 cities, including Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir. The immediate cause of the protests was a patch of green. Gezi Park is one of the green spaces close by Taksim Square in Istanbul. The mayor of Istanbul, a close buddy of the prime minister, had said the park would be cleared to make way for a replica of an old Ottoman barrack building and a shopping mall. And that did it. Hundreds, swelling to thousands, of young people headed for the Taksim Square area on Friday night. The protesters say the demolition of Gezi Park was a development too far by the increasingly autocratic prime minister and his AKP cronies.

AKP was formed out of two banned Islamic parties, forbidden under the secularist tradition of Turkey's constitution laid down by the founder of the modern nation, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

A successful general in the First World War, notably at Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal brought Turkey out of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The new nation was to be secular and western-looking, with an overt commitment to equality of opportunity for women. The paradox was that he made the army the guarantor of the state through a security council. There have been periodic military coups since Ataturk died in 1938. But the adage was "the army was always willing to march back to the barracks at the right time".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Though Ataturk was raised in the army, he believed in parliamentary democracy. When the dictators of Europe, Mussolini and Hitler, and the 'iron' monarchs of Romania and Yugoslavia "were donning their uniforms, Ataturk was putting his back in the wardrobe". Now Erdogan, described by some commentators as the most powerful political figure in Turkey since Ataturk, is accused of being high-handed and autocratic, criticised by moderate Islamic supporters and secularists alike. He has proposed a ban on the public sale of alcohol, he wants to name a projected new bridge over the Bosphorus after a reactionary Ottoman Sultan, and he's said to be aiming to become Turkey's next president – but with enhanced executive powers. Gezi Park was the last straw, too, because of the unsavoury whiff of sleaze beginning to swirl round the AKP party. Turkish Islamists now quip that the mujahids, or holy warriors, of yesteryear have become the muteahhids, the construction tycoons, of today. The demonstrations have come at tricky time for Turkey, given its ambiguous relations with the EU and its increasing entanglement with the crisis in Syria and Lebanon. The protests have united the old secular elites and the moderate Islamists who don't like what they see as the anti-democratic tendency of the AKP. One of the protests in Ankara demanded that the Erdogan government stop supporting the insurgents against Bashar el-Assad. This suggests that the wave of opposition is very different from the Arab Spring demonstrations of two years ago.

Erdogan shows no sign of backing down over Gezi Park, taunting the protesters by saying he could bring "tens of thousands" of supporters onto the streets, that his opponents are "alcoholics" and their use of Twitter "a curse" and a means of "extreme lying". The mild-mannered head of state President Abdullah Gul, a co-founder of AKP, has told the prime minister and the Istanbul mayor to cool it – and not to let "the accumulated energy" of the protests boil over.

Erdogan had won friends for seeking reconciliation with the revolutionary Marxist Kurdish Peoples Party, the PKK, until recently seen as terrorists. Today, he is only making enemies – and the trouble could deepen. The protesters want their say about what kind of state Turkey is to be – and they don't want to trade supervision by the military with the autocracy of Erdogan's alliance of Islamists and developers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

is a writer on Western defence issues and Italian current affairs. He has worked for the Corriere della Sera in Milan, covered the Falklands invasion for BBC Radio, and worked as defence correspondent for The Daily Telegraph. His books include The Inner Sea: the Mediterranean and its People.

-

Judge blocks Hegseth from punishing Kelly over video

Judge blocks Hegseth from punishing Kelly over videoSpeed Read Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth pushed for the senator to be demoted over a video in which he reminds military officials they should refuse illegal orders

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

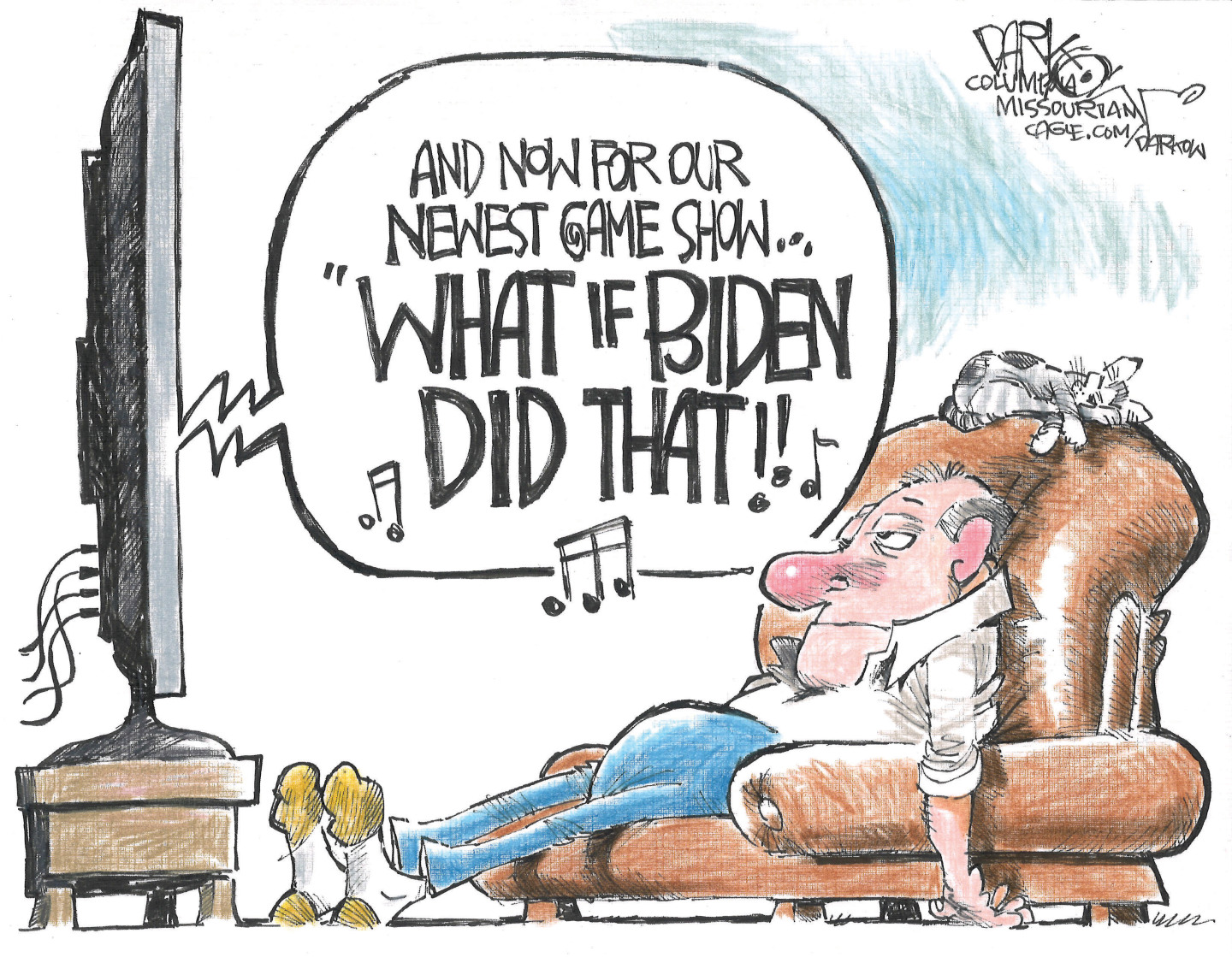

Political cartoons for February 13

Political cartoons for February 13Cartoons Friday's political cartoons include rank hypocrisy, name-dropping Trump, and EPA repeals

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military