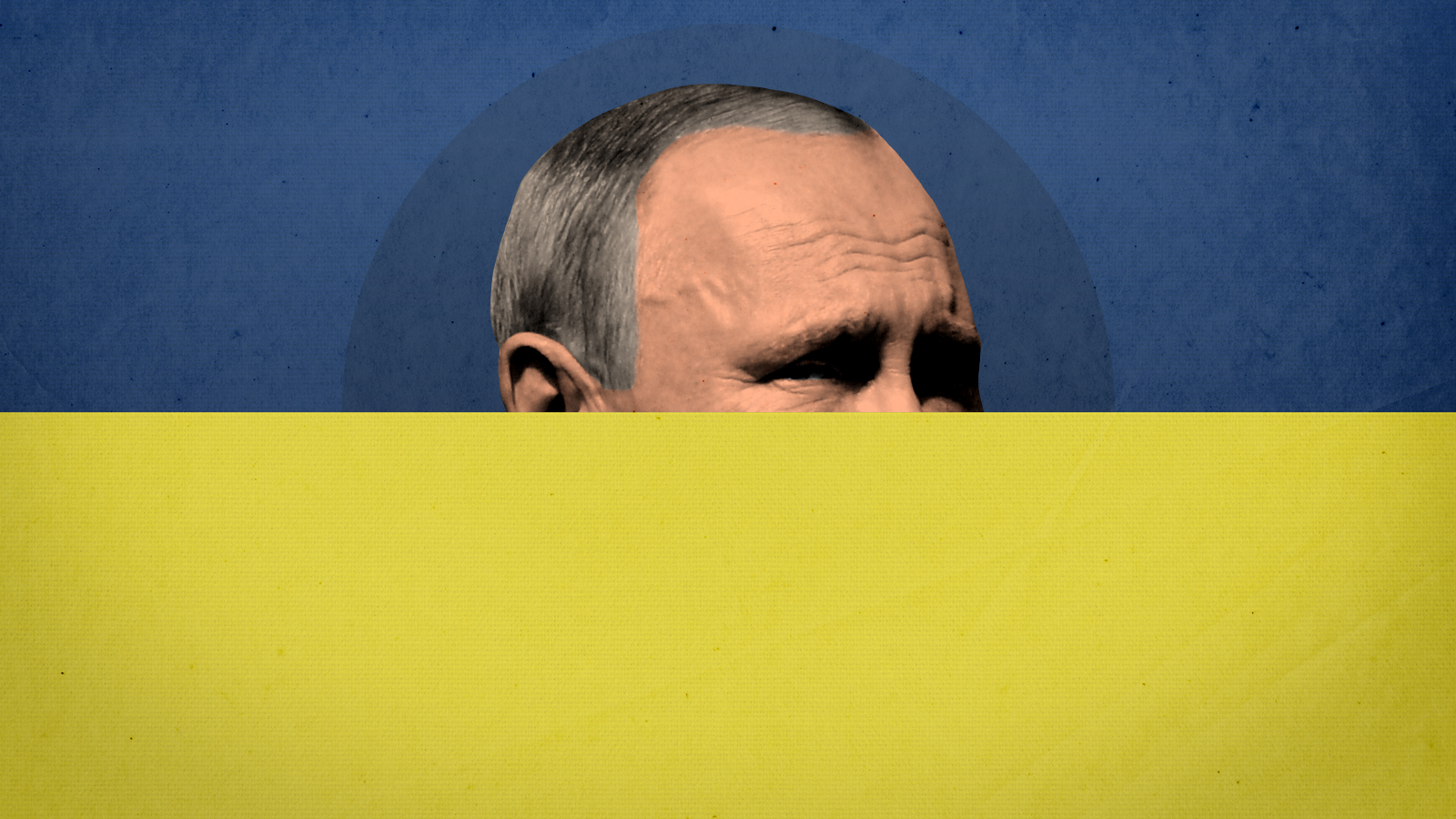

If we offered Russia a bridge out of conflict, would they buy it?

The mistaken assumption undergirding U.S.-Russia diplomacy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Next week, Western diplomats will meet with their Russian counterparts for a series of meetings that are likely the best opportunity to prevent a Russian invasion of Ukraine, for which 100,000 Russian troops are already poised on the border. The question is: What can the diplomats actually do to stop it?

Russian President Vladimir Putin's demands — an end to any further NATO expansion, not merely into Ukraine but anywhere; unilateral limits on deployment of American short- and medium-range missiles; and limits on troop deployments in NATO countries near Russia — are an obvious non-starter for the West. Agreeing would cut our European allies off at the knees at their moment of greatest concern about Moscow's ambitions. But by the same token, rejecting them out of hand, or offering drawn-out negotiations with no promise of achieving any meaningful Russian objectives, would only provide Putin with a pretext to invade. And since neither America nor our European allies have any intention of going to war with Russia in the event of an invasion, the prospect for deterrence seems equally dismal.

Assuming Putin is prepared for war, as he seems to be, forestalling it seems to require exceptionally creative diplomacy. Anatole Lieven of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft has proposed just that: neutrality for Ukraine, modeled on the Austrian State Treaty of 1955 between the Soviet Union, the United States, Britain, and France, as wel las the Soviet-Finnish treaty of 1948, which established Austrian and Finnish neutrality, respectively, during the Cold War.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Lieven's suggestion is that America offer Russia a "golden bridge" away from conflict, something that would satisfy Moscow's core security objectives without resorting to war or sacrificing core Western interests. The United States and NATO would permanently abjure NATO membership for Ukraine in exchange for Russia's agreement not to incorporate Ukraine into any alliance of its own. Ukraine would be required to implement the "Minsk II" protocol's provisions of autonomy for the Donbas region, and Russia would agree to withdraw its troops there. By these means, Ukraine would become a neutral buffer state. This would avoid war, Lieven argues, satisfy Russia's need to keep Ukraine out of the Western orbit, and not compromise Ukraine's own independence or NATO's credibility.

It sounds like an elegant solution — a way for the West to limit Russian expansion while avoiding an expensive and dangerous new liability. But it's premised on the assumption that both sides actually want to avoid conflict. I suspect that assumption is false.

As Lieven himself recognizes, Russia's paramount objective for over a decade has been to incorporate Ukraine into a Russian sphere of influence as a compliant satellite state dependent economically and militarily, akin to Belarus or Kazakhstan (Russia has just dispatched troops to the latter to quell a popular uprising). A truly neutral Ukraine would represent a significant setback for Russian regional ambitions. Why accept that? More than likely, if Russia entertained the proposal, it would be for the purpose of preventing the further modernization of Ukraine's military and limiting its economic drift westward, making neutrality a mere way station on the path to Russian dominance.

For that very reason, neutrality might well be rejected by Ukraine itself and would be interpreted more generally as an affirmative declaration on the part of the West that it respects a distinct Russian sphere of influence. Since the end of the Cold War, the West has never formally recognized or accepted this, neither for Russia nor for any other power. It might well be a salutary development to do so — but it's not a move the West is likely to undertake lightly. Indeed, many American foreign policy professionals might privately prefer a situation where Russia seized a chunk of Ukraine and became further isolated in consequence, leaving western Ukraine to become a more avowedly pro-Western state with irredentist claims against Russia. Such an outcome wouldn't require anyone to back down from their ideological commitments.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That preference may be present in Moscow as well. We don't know how extensive Putin's territorial objectives are with regard to Ukraine, but at a minimum it seems reasonable to assume he aims to establish a land bridge to the Crimean peninsula. Maximally, he might be planning to seize all of the Ukrainian territories included in so-called "Novorossiya." If Putin believes he could achieve those aims easily by force and thereby demonstrate the West's impotence to stop him, he might well prefer near-term conflict even over a relatively favorable settlement, since time might not always be on his side.

Indeed, time never is. That's the great mistake the West made at the end of the Cold War: assuming the unipolar moment of Western and, more specifically, American dominance was or could be a permanent condition. If there was a time to cement a new relationship with Russia on the basis of respect for its own diminished sphere of influence, that time was the 1990s, when the United States was at the peak of its relative power. Now we don't have the choice of going back; we must deal with a Russia determined to reverse what it sees as a period of humiliation and reset the terms of European order.

In that context, if we offer to sell them a bridge — even a golden one — I find it hard to believe they'd buy.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisonings

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisoningsThe Explainer ‘Precise’ and ‘deniable’, the Kremlin’s use of poison to silence critics has become a ’geopolitical signature flourish’

-

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty ends

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty endsSpeed Read New START was the last remaining nuclear arms treaty between the countries

-

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Weapons experts worry that the end of the New START treaty marks the beginning of a 21st-century atomic arms race

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law