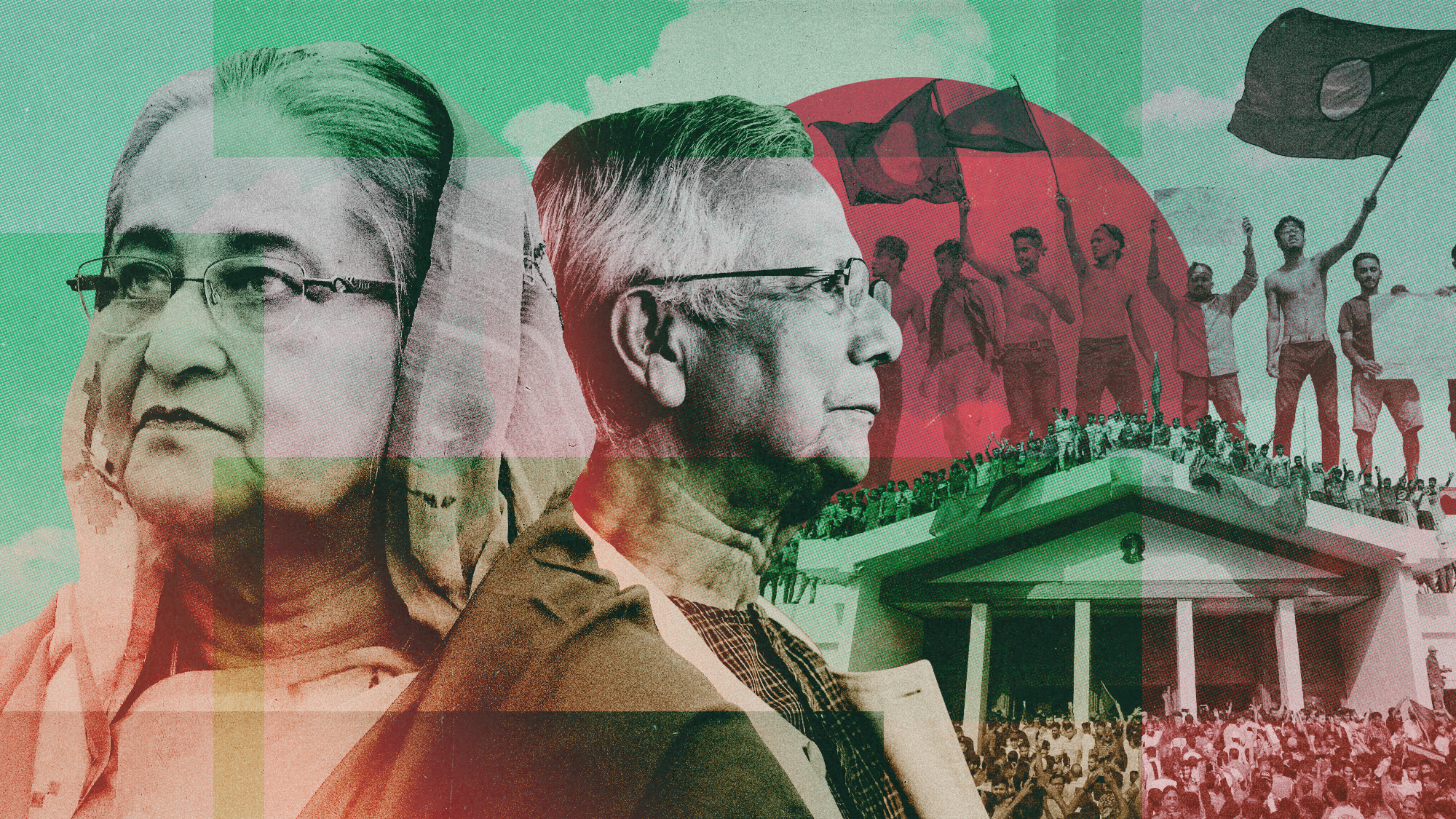

Will the resignation of Bangladesh's prime minister usher in a new wave of democracy?

The prime minister resigned after weeks of violent protests over a quota system

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Bangladesh will have a new leader for the first time in over a decade, as Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina resigned on Monday, fleeing the country by helicopter. The head of the Bangladesh Army, Gen. Waker-uz-Zaman, confirmed the news and also announced that he was forming an interim government, to be led by Nobel Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus, in what he described as a "critical time for our country."

Hasina's resignation comes following weeks of anti-government protests by students, sparked by anger over a newly implemented quota system for civil service jobs. Hasina had ruled Bangladesh since 2009 and was often described as an authoritarian. Her time in power was "marked by an economic rebirth but also by the mass arrest of political opponents and human rights sanctions against her security forces," said AFP.

With the world's longest-serving female head of government now ousted, questions are swirling as to what this means for Bangladesh. Where does the country's interim leadership go from here, and will there be a shift away from the democratic backsliding seen during Hasina's rule?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What did the commentators say?

Hasina's political prowess and longevity "relied on tacit backing from the army and on increasing oppression," and "until last month it looked as if Sheikh Hasina's formula for maintaining power still worked," said The Economist. But once the throng of protests started, Hasina was "faced with the prospect of inflicting large-scale bloodshed in order to defend a decaying regime," and "concluded that her position was untenable." The question now becomes "whether, after a period of caretaker military rule, a credible democratic system can be rebuilt."

Complicating matters, "Hasina's position always relied on Bangladesh's military, which has historically meddled in politics" and until recently had been "staunch backers" of Hasina's political party the Awami League, said Charlie Campbell at Time. The military generals were "likely assessing the 'resilience capacity of the movement in the face of repression,'" Ali Riaz, a Bangladeshi-American political science professor at Illinois State University, said to Time. This means the "fall of Hasina is only the first step in what will no doubt be a bitter reconciliation process," as "with practically every government institution politicized by the Awami League, distrust of the security services, military, courts, and civil service runs deep across society."

Religious clashes could also hinder any democratic shift. There is a "feeling that India completely backed Sheikh Hasina's government. Protesters make no distinction between India and Hindu citizens of Bangladesh, which has already led to attacks on temples and people," Debapriya Bhattacharya, an economist at the Center for Policy Dialogue in Bangladesh's capital, Dhaka, said to the BBC. With Hasina ousted, there is a "power vacuum, there is nobody to implement law and order. The new government will need to protect religious minorities."

What next?

It's unclear what the future holds for Bangladesh. The army has "asked the president, who holds a ceremonial role, to form a new government," but Bangladesh's military "has a history of staging coups and counter-coups," said The New York Times. However, the military "has taken a less overt role in public affairs" in recent years.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The president of Bangladesh did answer the army's request, along with pressure from the student protesters, and dissolved the country's parliament a day after Hasina's departure. This paves the way for new national elections in the country to be held in the near future. Bangladesh "had an imaginary election in the past. Now we need a real election," interim government leader Yunus, who was a common target of Hasina's ire, said to The Washington Post.

And the military has been working to try and quell fears of continued oppression, though this could be easier said than done in a country that is "already dealing with a series of crises, from high unemployment and corruption to climate change," said The Associated Press. As Zaman works to form an interim government, the general "sought to reassure a jittery nation that order would be restored," adding that he had "ordered security forces not to fire on crowds" of protestors. Zaman also "met with opposition politicians and civil society leaders" to try and find the best path forward.

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

‘My donation felt like a rejection of the day’s politics’

‘My donation felt like a rejection of the day’s politics’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why is Tulsi Gabbard trying to relitigate the 2020 election now?

Why is Tulsi Gabbard trying to relitigate the 2020 election now?Today's Big Question Trump has never conceded his loss that year

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

Minnesota roiled by arrests of child, church protesters

Minnesota roiled by arrests of child, church protestersSpeed Read A 5-year-old was among those arrested

-

How Iran protest death tolls have been politicised

How Iran protest death tolls have been politicisedIn the Spotlight Regime blames killing of ‘several thousand’ people on foreign actors and uses videos of bodies as ‘psychological warfare’ to scare protesters

-

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?Today’s Big Question Centrists, lefty activists also debate abolishing ICE

-

‘It may portend something more ominous’

‘It may portend something more ominous’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Unrest in Iran: how the latest protests spread like wildfire

Unrest in Iran: how the latest protests spread like wildfireIn the Spotlight Deep-rooted discontent at the country’s ‘entire regime’ and economic concerns have sparked widespread protest far beyond Tehran