What if the culture war never ends?

It seems the only things we agree on are the institutions that keep us apart

In a book published in 2010, I proposed that America had become a "centerless society" lacking a consensus about the highest human goods. It is this inability to agree on ultimate ideals that fuels the culture war, I argued, with some people devoting themselves to God (believing that abortion is murder, and defining marriage exclusively as a "one-flesh union" between a man and a woman) and others rejecting God (defending a woman's absolute right to terminate a pregnancy, and advocating the freedom of gays to marry).

I also proposed a solution to our cultural conflicts — or rather, a way of coming to accept them as a permanent fact of modern life. Instead of one side continually attempting to triumph decisively over the other, the American tradition of federalism might be used to allow us to live in acceptance of our centerlessness.

And now it's happening. Several states have passed significant restrictions on abortion, while many others continue to keep it freely available. A number of states have legalized gay marriage, while others resist the change. The same dynamic is now also taking shape around pot legalization, with a handful of states moving to permit marijuana purchases and some others going out of their way to reaffirm prohibition.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This is precisely what I advocated in my book.

So why am I worried?

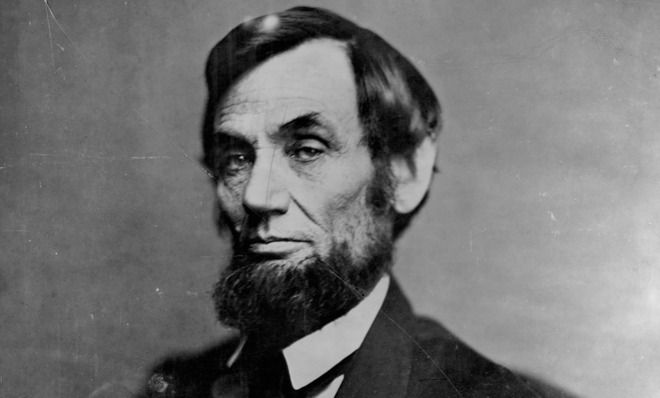

Because I can't get Abraham Lincoln out of my head.

In theory, the American states are supposed to be laboratories of democracy, free to experiment with building different and divergent local cultures. But America has also had concrete historical experience with cultural diversity leading to serious trouble. In his legendary 1858 debate with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln famously pronounced that "a house divided against itself cannot stand" — that big cultural questions ultimately need to be decided one way or another at the level of the nation as a whole.

It took fewer than three years for Lincoln's dire prediction to be fulfilled.

What about the issues that divide us today?

The legal issues are fairly straightforward. If I had to wager a guess, I'd predict a mixed bag of results: The courts will ultimately force gay marriage to be accepted across all 50 states, some of the new abortion restrictions will be overturned but others will be upheld, and the states will be given maximum latitude to experiment with a range of options with regard to the legal status of marijuana sales and use.

The bigger problem is culture. We've all caught ourselves wondering at one time or another if the country is coming apart at the seams, with anti-abortion activists and defenders of traditional marriage squared off against abortion rights groups and gay-marriage advocates. Cable-news and talk-radio personalities, along with demagogic politicians, might exploit and exacerbate these and other fissures, but the divisions were already there — and thanks to those troublemakers, as well as a multitude of sociological factors, they appear to be getting worse.

The old talk of a red state/blue state divide got at part of what's going on culturally, but only a small and misleading part. Even the bluest state has red communities within it, and the same holds for blue areas in red states. Looked at through different lenses, our divisions can be described as regional (North vs. South; coasts vs. heartland), geographical (urban vs. rural), intrareligious (traditionalist believers vs. liberal believers), interreligious (observant vs. secular), and technological (like-minded people coming together online and forming ideologically and morally homogenous communities without regard for real-world distances).

The result looks an awful lot like the cultural fracturing of the United States.

The liberal political theory that influenced and inspired America's founders tells us that these disagreements shouldn't be a problem. First devised in response to the bloody clashes of Europe's religious civil wars, classical liberalism proposes that a modern, liberal nation can cohere around devotion to the ideals and institutions that make it possible for its citizens to live together freely and in peace, despite their differences about the highest human goods.

But is that really enough when the differences go so far beyond early modern Christian factionalism, to include disagreements about fundamental questions of life, love, sex, pleasure, family, and even the very nature of reality and meaning of existence? Is there any upward limit on how much cultural difference is compatible with national cohesion? How long are Americans stationed on different sides of our numerous cultural fissures likely to feel bound together with strangers who view the world so very differently — especially when each side increasingly treats the others with open contempt?

Can a nation of more than 310 million people bind itself together with little more than an attachment to the very institutions that permit and foster its cultural disunity?

In 1858, Lincoln predicted that the United States was destined to become "all one thing, or all the other." He found it impossible to imagine America trying to split its differences forever.

When it came to slavery, Lincoln was undeniably correct.

We have yet to determine if his ominous insight applies equally well to the innumerable issues that divide us today.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Why has Tulip Siddiq resigned?

Why has Tulip Siddiq resigned?In Depth Economic secretary to the Treasury named in anti-corruption investigations in Bangladesh

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

The controversy over rewilding in the UK

The controversy over rewilding in the UKThe Explainer 'Irresponsible and illegal' release of four lynxes into Scottish Highlands 'entirely counterproductive' say conservationists

By The Week UK Published

-

How to decide on the right student loan repayment plan

How to decide on the right student loan repayment planThe explainer President-elect Donald Trump seems unlikely to approve more student loan forgiveness, so you may want to consider other options

By Becca Stanek, The Week US Published

-

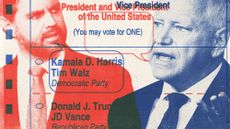

US election: who the billionaires are backing

US election: who the billionaires are backingThe Explainer More have endorsed Kamala Harris than Donald Trump, but among the 'ultra-rich' the split is more even

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK Published

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockade

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockadeSpeed Read Only one of the accused was found liable in the case concerning the deliberate slowing of a 2020 Biden campaign bus

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?Today's Big Question Trump's hawkish pick for VP said UK is the first 'truly Islamist country' with a nuclear weapon

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Biden, Trump urge calm after assassination attempt

Biden, Trump urge calm after assassination attemptSpeed Reads A 20-year-old gunman grazed Trump's ear and fatally shot a rally attendee on Saturday

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published