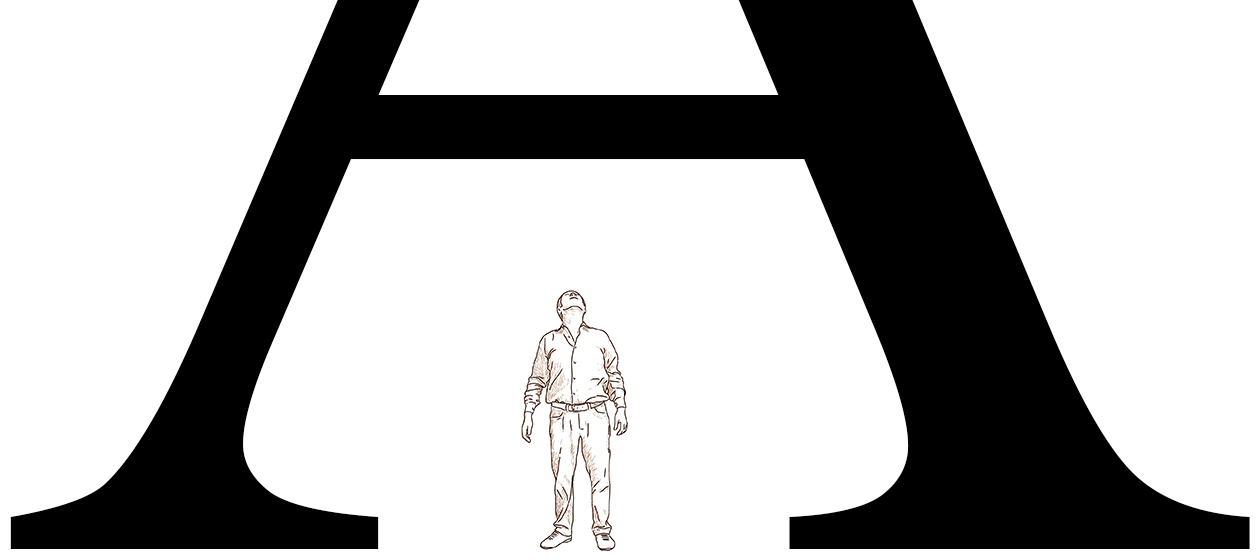

There's no such thing as an 'illegal immigrant'

And other things Jose Antonio Vargas wants you to know

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Here is something you probably don't know about illegal immigrants in the United States. There aren't any. Zero. The term, on its face, is willfully misleading.

It is not a crime to emigrate to the United States without a visa. The punishment for overstaying a visa, or for having been discovered in the United States without a visa, is not a criminal penalty. It is a civil remedy; an administrative sanction. That's because the executive branch has the primary right to decide who gets to stay here and who doesn't. So the phrase "undocumented immigrant" is not a politically correct, less-than-harsh way of referring to what are commonly called "illegal immigrants." It's much more accurate.

Things like this really irritate Jose Antonio Vargas.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 2011, Vargas became a national spokesperson for the rights of the undocumented when he penned a New York Times magazine article explaining his decision to come out as an undocumented immigrant. Vargas was born in the Philippines. When he was young, his grandparents managed to bring him to the United States. Then they contrived to keep him here past the expiration date of his visa. He grew up, unaware that he was not a permanent resident until, at the age of 16, he was told that the papers he presented to document his status at the California Department of Motor Vehicles were fake.

I first met Vargas in 2005, when he was a reporter for The Washington Post. He would later help the paper win a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the Virginia Tech massacre. I remember our first meeting because he asked me a lot of questions. A lot of questions. I later guessed that he asked me a lot of questions so I wouldn't ask him too much about his own past. He did not want to have to lie to another person.

On Friday, Vargas' extraordinary film, Documented, opens in New York City. CNN will air the documentary later this summer. I recommend it highly. It is sad and funny, poignant without being preachy, and potentially game-changing. But, as his friend, you'd expect me to praise his film, so I might not be an unmotivated critic.

After a screening in Los Angeles a month ago, I talked to Vargas about his activism. The transformation from writer to activist was not easy. Vargas doesn't follow talking points. He likes discursions and tangents. He is not unsympathetic to critics of immigration reform. Unlike a lot of activists I know, he tries to find common ground with his opponents. He also calls out his own side. He is not a huge fan of President Obama's, and doesn't really mind if the White House gets wind of this. (Until very recently, Obama was essentially deporting almost every undocumented immigrant with a misdemeanor on the books.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Vargas is gay, too. He came out when he was a junior in high school.

There is a correspondence between the gay rights movement and the movement he is now a leader of. There are many obvious differences, of course, but the similarities are pretty deep, and Vargas is a unique position to see them. He wants gay rights advocates to open their eyes a bit wider. His argument is pretty compelling.

"When I came out as an undocumented person and did an initial round of publicity, I had some people reach out to me and say that I'm not being gay enough. But here I am, on Rachel Maddow and Colbert talking being undocumented but I didn't bring up being gay. And they would say to me, you know, you need to be a little gayer. You talk about being undocumented and not enough about being gay. And I thought I was being appropriately gay enough." (Colbert, true to form, did call Vargas a "border gay." His sexual orientation did not come up during contentious interviews with Lou Dobbs and Bill O'Reilly.)

Vargas notices "so many undocumented young leaders are also openly gay." Why? "Cause I think that we are coming out? Is it any accident that undocumented people use the term coming out? Right? We've grown up in this era of coming out. Coming out as a way of letting people in. And I mean by that, coming out as a way of letting people know about rights, about access. About citizenship."

He hopes that the undocumented immigrants rights movement will emulate the successes of the incredibly rapidly germinating gay rights movement, including its targeted cultural and media advocacy ("culture trumps politics," he says), wily political engagement, personalizing individual experiences and stories, influencing corporate values and picking and choosing their battles carefully.

Vargas thinks that gay rights leaders have a moral responsibility to help. There's a ways to go before full equality is realized, of course, but arguing over who gets credit for what is the hallmark of a mature political movement.

"There needs to be more leadership in words and actions from the LGBT community on this issue. I don't see it to the extent that we should given how much these two issues intersect. Among the two defining civil rights movements of our time are LGBT rights and immigrant rights. And what are they both about? They're both about the fact that America is changing, demographically and culturally. The country will only get gayer, the country will only get more Latino and more Asian. Those are inevitabilities."

"There hasn't been an aggressive, bold sense of community between these two groups," he says. "One one my jobs is to connect the dots."

Last month President Obama went to the LBJ Library in Texas to celebrate the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Next year is the 50th anniversary of something that shaped our society almost as much: the 1965 Immigration and Nationalities Act, which forever changed the demographic seams of America. In 1965, the racist quote system that governed immigration since 1920 was replaced by a series of rule-based preferences for family cohesion and economic contributions. It was much fairer, in more tightly linking citizenship to what individuals were able to do for America. The 1965 Immigration and Nationalities Act is why a majority of children being born today in America are not white.

Vargas, gay, from the Philippines, undocumented, is a leading light of the movement today, but by next year, in part because of the film, he will be a celebrity, albeit one with a huge task on his shoulders.

"This is a time to really go to uncomfortable places and get people uncomfortable. Look, I have been uncomfortable my whole life. I can stand a little discomfort."

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Trump wants a weaker dollar but economists aren’t so sure

Trump wants a weaker dollar but economists aren’t so sureTalking Points A weaker dollar can make imports more expensive but also boost gold

-

Political cartoons for February 3

Political cartoons for February 3Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include empty seats, the worst of the worst of bunnies, and more

-

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ire

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ireSpeed Read Trump said he will close the center for two years for ‘renovations’

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

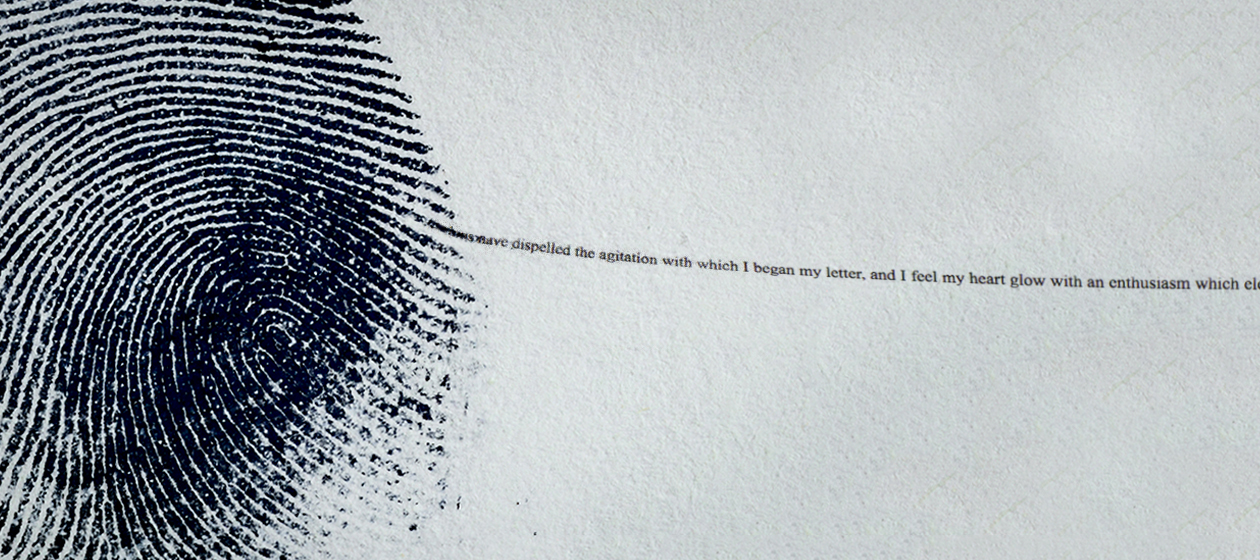

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

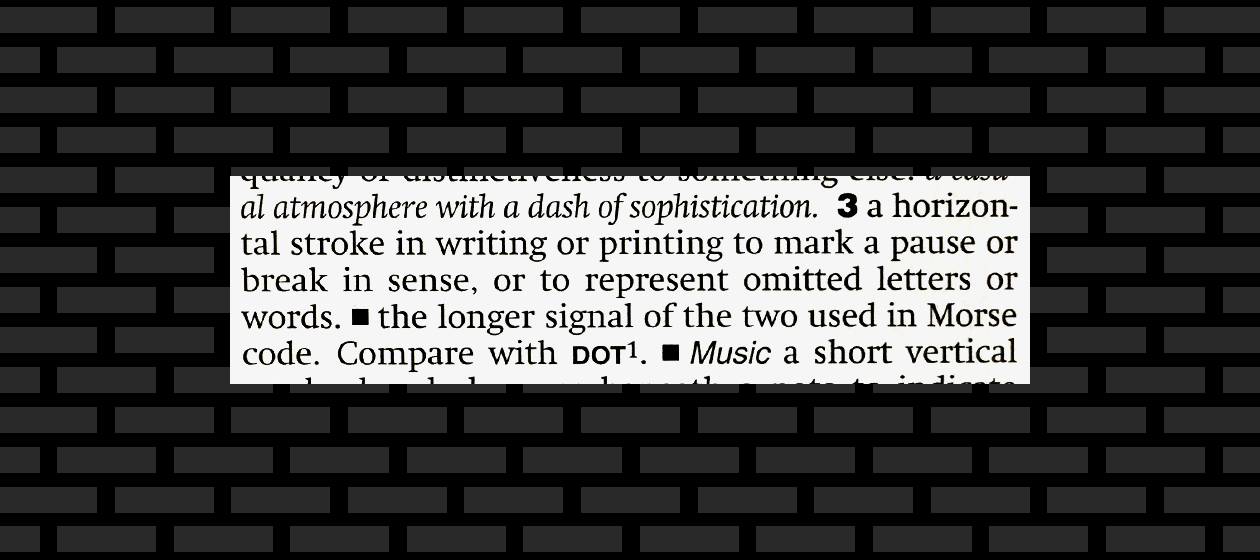

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.