It's time to declare war on climate change — literally

Mobilizing all the U.S.'s resources will not only stave off catastrophic global warming, but also encourage innovation and economic progress

In America, our use of war as a metaphor for a public policy initiative — whether it's on drugs, crime, poverty, litter, or cancer — is matched only by our lack of actual declarations of war when it comes to fighting people around the world. But it is time to dust off this tired concept and infuse it with its original meaning for an issue that actually necessitates all-out war: climate change.

Constant overuse has eroded declaring war on a domestic problem to mean a milquetoast, halfhearted policy doled out to some Cabinet secretary or the other. But real war is something else entirely. It means mobilization, historically perhaps the most significant action that any government undertakes.

As Tyler Cowen points out, war can have a huge, positive impact on the economy:

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Fundamental innovations such as nuclear power, the computer, and the modern aircraft were all pushed along by an American government eager to defeat the Axis powers or, later, to win the Cold War. The internet was initially designed to help this country withstand a nuclear exchange, and Silicon Valley had its origins with military contracting, not today's entrepreneurial social media startups. The Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite spurred American interest in science and technology, to the benefit of later economic growth.

War brings an urgency that governments otherwise fail to summon. For instance, the Manhattan Project took six years to produce a working atomic bomb, starting from virtually nothing, and at its peak consumed 0.4 percent of American economic output. It is hard to imagine a comparably speedy and decisive achievement these days. [The New York Times]

This piece has gotten a lot of flak for its trolly headline ("The lack of major wars may be hurting economic growth"), but it's a fair point. As I've argued before on the topic of infrastructure, an emergency knocks some urgency into our decrepit and dysfunctional institutions, and all of a sudden America is capable of great things.

So I don't mean declaring war on climate change in a Race for the Cure kind of way. I mean literally putting the United States on something like a war footing. Back in WWII, this meant stoking the economy to a fever pitch with deficit spending to wring out every last scrap of materiel, while controlling inflation with price controls, rationing, and forced saving.

A war on climate change wouldn't be quite like that, since we're not trying to maximize industrial output. But it would mean similarly aggressive government action to implement a crash transition from a carbon-based economy to one anchored in renewables and nuclear. (See here for more on what such a mobilization would look like.)

There has long been a debate about whether planning-based or market-based policies would be more effective in reducing emissions. The market-based approach — which would include a stiff carbon tax that ratchets up — does have much to recommend it. But people hate taxes. Especially in this country, we like our policy hidden in the tax code and inside Byzantine regulations, so we can pretend like we're not spending money when we really are.

Conservatives, needless to say, will hate the war plan. But take note that this scenario assumes a pileup of climate disasters that will eventually force the government to leap into action. If conservatives want to avoid the mobilization option, they should start demanding market-based policy tomorrow. For if climate change worsens, nations may not have a choice.

But in the end, I suspect an emergency is what it will take for the country to deal with this crisis. Historically, the American way of tackling serious problems is to dither and bicker and procrastinate until we are so far down the maw of the crisis that we're grazing its tonsils, then suddenly snap into action with incredible speed and vigor. We're not there yet, and we may not be capable of that anymore, but if we're going to deal with climate change, that may be the only realistic way out.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

In search of paradise in Thailand's western isles

In search of paradise in Thailand's western islesThe Week Recommends 'Unspoiled spots' remain, providing a fascinating insight into the past

-

The fertility crisis: can Trump make America breed again?

The fertility crisis: can Trump make America breed again?Talking Point The self-styled 'fertilisation president', has been soliciting ideas on how to get Americans to have more babies

-

The fall of Saigon

The fall of SaigonThe Explainer Fifty years ago the US made its final, humiliating exit from Vietnam

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

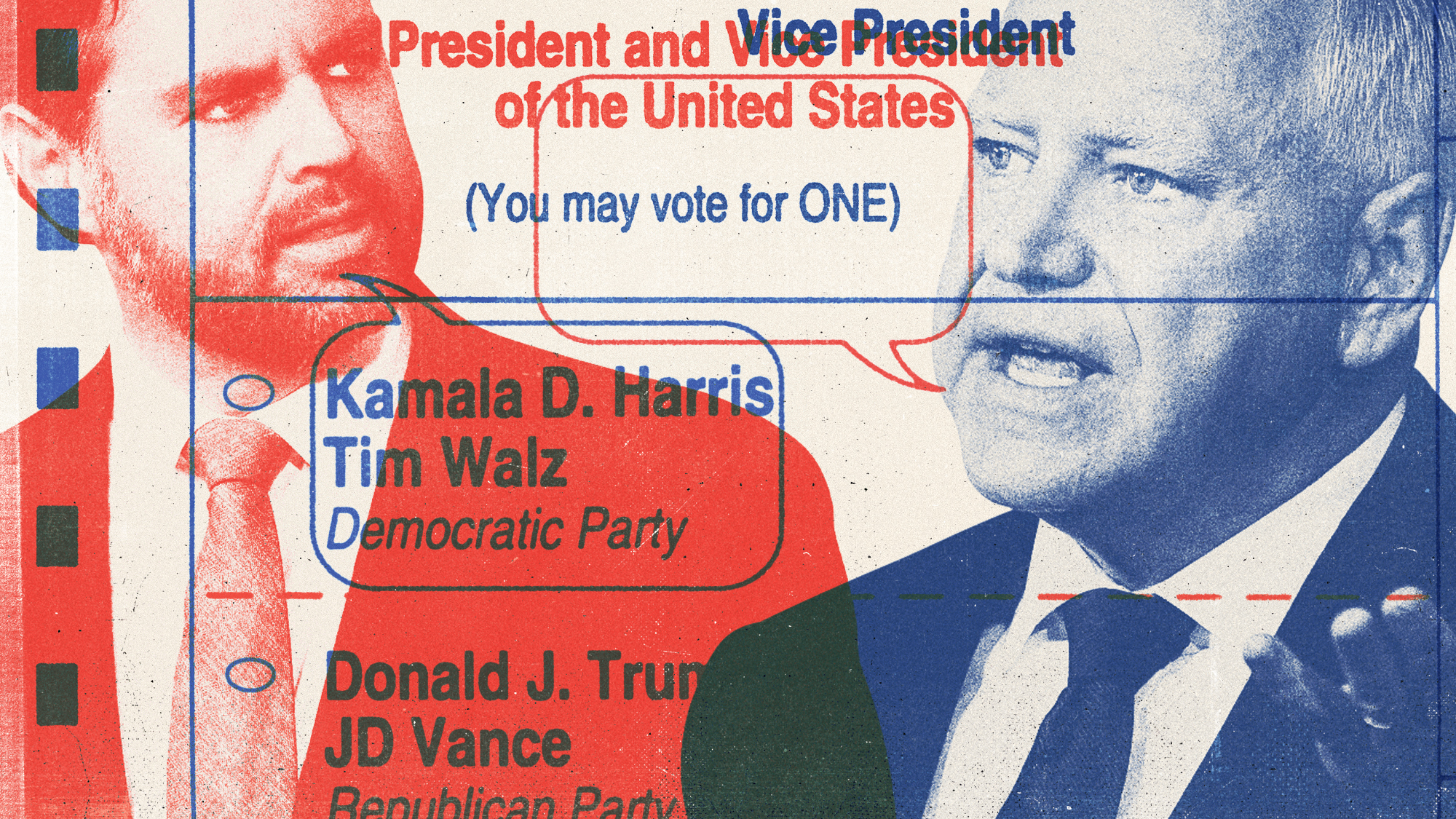

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy