What liberals can learn from the author of The Culture of Narcissism

Christopher Lasch's books offer a counter-narrative of historical decline and dissolution that should make the Left think twice about its progressive achievements

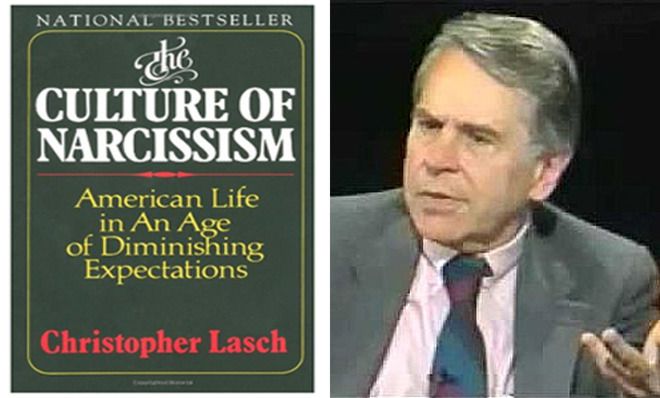

Twenty years ago today — Valentine's Day 1994 — America lost Christopher Lasch to cancer at the criminally young age of 61. One of the country's most creative historians and path-breaking intellectuals, Lasch wrote works that remain essential reading for anyone who aspires to cultural literacy.

The New Radicalism in America 1889-1963 (1965) lent scholarly rigor and literary panache to the New Left's savage critique of New Deal liberalism. The Culture of Narcissism (1979) laid bare the psycho-social pathologies of post-1960s America with unmatched intensity and depth; unlike most examples of cultural criticism, it has only gained in explanatory power in the years since it appeared.

But it is Lasch's final, overlooked masterpiece The True and Only Heaven (1991) that has the most to teach us today — and none more so than his compatriots on the Left. A sprawling, radically revisionist 570-page cultural and intellectual history of the United States, the book is a time bomb sitting on the bookshelf, primed to explode the pieties of progressives.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The book derives much of its power from its rejection of a historical narrative that so often sets the terms of discussion and debate in academic scholarship, as well as in the broader culture. We all know the drill: Modern American history is a story of progress and reaction; the Left works to advance justice and equality while the Right fights to turn back the clock.

Conservatives reject the insinuation that they're merely holding back inevitable and desirable progress, of course, but they tend not to question the overall shape of the story. They see progressive reforms as deviations from a political and economic order that protects individual freedom and economic opportunity; as far as they're concerned, turning back the clock would be its own triumph for progress.

All of Lasch's political convictions and scholarly instincts told him that this account of American history — in which competing forces of progress and reaction do battle and flip roles depending on who is telling the tale — was wrong. It was a just-so story, he argued, designed to legitimate and further entrench the reigning ideologies of the postwar United States.

Lasch's career can be seen in retrospect as a long, arduous effort to break the hold of this narrative on academic history and American political culture, to scramble its characters, categories, and plot, and, finally, to construct an alternative history that would be both truer to the past and more useful in building a future in which America's democratic promise might be fulfilled.

It was not, primarily, a project pursued in dusty archives, but rather one that grew out of Lasch's passionate lifelong intellectual engagement and contestation with the social theorists who tried to make sense of modern life in the most radical terms: Sigmund Freud and his psychoanalytic descendants; communitarian philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre; theologian Reinhold Niebuhr; and Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and the other critical theorists of the Frankfurt School for Social Research.

All of these thinkers and many more influenced the shape of Lasch's alternative history as it developed in his writings of the 1970s and '80s. But only in The True and Only Heaven did it come together into a fully formed counter-narrative.

In place of the familiar story about the steady rise of progressive ideology from the late 19th century through 1933, and then its triumph in the New Deal and the postwar political and economic order, with a few minor latter-day setbacks (Ronald Reagan and the New Right), Lasch constructed a narrative of decline and dissolution.

In Lasch's view, the mainstream progressive Left lost its way as soon as it set itself the task of saving capitalism from its excesses rather than proposing a more radical critique of the social, moral, and economic damage it does to settled ways of life. Instead of championing the well-being of average Americans, the Left came to valorize ideals of consumption and meritocratic striving. Along the way, it also fetishized efficiency and productivity as measures of the good life, and bought into the notion that the nation should strive for constantly expanding economic growth, with individuals chasing endlessly after a standard of abundance that's always just out of reach.

The result is widespread spiritual misery (and accompanying social pathologies, including violence, drug addiction, and depression), as Americans spend their lives in grinding pursuit of a fulfillment in luxury, novelty, and excitement that can never be achieved.

Perhaps the most controversial element of Lasch's argument, then no less than now, was his assertion that the Left's advocacy of the sexual revolution was in fact a betrayal of both women and the working class. Whereas the family was once a "haven in a heartless world" (to cite the title of the book in which Lasch first advanced the claim), the sexual revolution encouraged its near-total assimilation into the capitalist order of consumption and exchange. Men and women now both pursued careers outside the home, spreading the spiritual malaise deeper into the life of the nuclear family, which turned unplanned pregnancies into inconveniences and additional children into burdens rather than blessings. This, in turn, required parents to hire expensive professional child-care providers to serve as surrogate caregivers, provoking waves of ambivalence and guilt in both parents.

For wealthy and upper-middle-class families, this way of living might be spiritually dismal, but at least it's economically viable — and compatible, in many cases, with women taking time off from their careers to focus, if they wish, on motherhood. But for the working class, life in post-sexual-revolution America can be far bleaker. Where once a blue-collar manufacturing job allowed a man to provide his family with a decent life, now both adults in the family have to work often crushingly long hours just to keep their heads above water. No wonder that under those conditions, more than half of all working class families fall apart, with one or the other of the spouses taking advantage of yet another reform championed by the Left — no-fault divorce laws — to ditch the sinking ship.

The bulk of The True and Only Heaven is devoted to constructing a tradition that could serve as an alternative to progressivism and its ill-fated role as facilitator to capitalism. The term he used to describe this alternative tradition was populism. It included the anti-industrialist, agrarian Populist movement of the 1890s (led by William Jennings Bryan), but Lasch maintained that it could be found in many other times and places throughout American history. The Puritans, Jonathan Edwards, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Orestes Brownson, William James, Martin Luther King — all of them and many other lesser known writers and political figures championed the populist vision.

It's a vision rooted in a lower-middle-class ethic that holds up a view of the good life tied to family and local community. It rejects the shallow ideological optimism that animates liberationist projects of the Left and Right in favor of a more tentatively hopeful affirmation of intractable moral and economic limits on human freedom — and the humble vision of human happiness, democracy, and citizenship implied by those limits.

Did Lasch's merciless critique of progressives and defense of working-class mores make him a conservative, as so many leftist critics and right-wing admirers have insisted in the years since his death?

Perhaps — but only if we radically redefine what it means to be a conservative. Lasch remained deeply suspicious of the Reaganite New Right, with its mania for tax cuts and deregulation, to the very end of his life. And there can be no doubt that he'd be even more outraged at the libertarian selfishness of the Tea Party, as well as the contemporary GOP's elitist idealization of entrepreneurial supermen and consequent disparagement of those at the bottom of the economic hierarchy as "moochers."

Lasch was a man without a party. Or a political movement. He refused to tailor his convictions to the categories that set the boundaries of our culture's conversation about how we should live and govern ourselves. Instead, he used every ounce of his intellect and energy to change that conversation.

When Lasch died, he was a voice crying out in the wilderness. Twenty years later, the conversation continues in its well-worn grooves, largely unchanged by his provocation. Yet the voice remains, preserved in his books, ready to be heeded.

If only we will listen.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Today's political cartoons - February 22, 2025

Today's political cartoons - February 22, 2025Cartoons Saturday's cartoons - bricking it, I can buy myself flowers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

5 exclusive cartoons about Trump and Putin negotiating peace

5 exclusive cartoons about Trump and Putin negotiating peaceCartoons Artists take on alternative timelines, missing participants, and more

By The Week US Published

-

The AI arms race

The AI arms raceTalking Point The fixation on AI-powered economic growth risks drowning out concerns around the technology which have yet to be resolved

By The Week UK Published

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

US election: who the billionaires are backing

US election: who the billionaires are backingThe Explainer More have endorsed Kamala Harris than Donald Trump, but among the 'ultra-rich' the split is more even

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK Published

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockade

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockadeSpeed Read Only one of the accused was found liable in the case concerning the deliberate slowing of a 2020 Biden campaign bus

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published