The science of making a guitar sound like a human voice

Or what puts the "wah" in the wah-wah

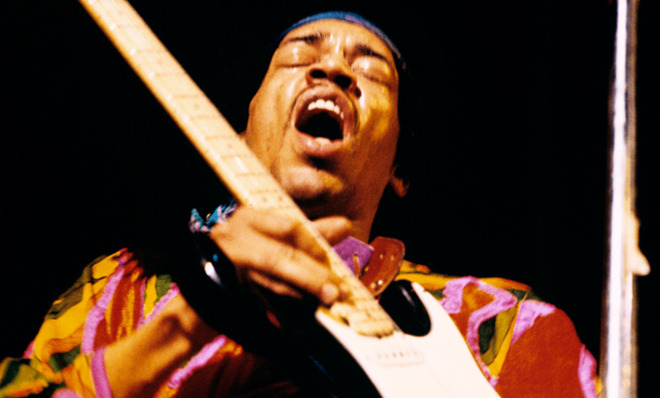

The wah-wah pedal makes a guitar sound as though it's singing "wah, wah, wah." The effect was a staple of 1960s psychedelic rock: Jimi Hendrix bent reality with it in classics like "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)," Eric Clapton cut loose with it on hits such as Cream's "White Room," and even Led Zeppelin's Jimmy Page made use of it on occasion ("Dazed and Confused").

The wah-wah pedal didn't disappear after the '60s, either; its distinctive sound has been carried on by the likes of Guns N' Roses, Metallica, David Bowie, and more.

But do you have any idea how it works? The guitarists aren't passing the sound through their mouth with a tube (though Peter Frampton and others have done that with a "talk box"). The wah-wah pedal is just an electronic device with a foot pedal.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So how does that pedal make a guitar sound like a human voice? By altering the harmonics — which is exactly what your mouth does when you talk. I'm going to demonstrate how that works.

We may think that the sound we make when speaking or singing is a single note that gets somehow "shaped" by the mouth when it passes through. But actually, any sound you make with your voice — or with a musical instrument such as a guitar — has not just the main note but a whole bunch of harmonics above it.

For instance, if you're singing a note at 150 Hertz (150 vibrations of the vocal cords per second), you will also have notes at 300 Hertz, 450 Hertz, 600 Hertz, etc. And it's the volume of each level that helps us differentiate speech sounds.

Listen to this: It's just "wah wah yeah yeah" sung on a single note.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now listen to this: This is just the basic note extracted from that, about 150 Hertz, without any of the higher harmonics.

Where did the "wah" and "yeah" go?

Here's what makes the difference: Your mouth is a resonating chamber. Actually, it's two resonating chambers (in fact, more than two, but two main ones): One at the back, behind your tongue and above your larynx; and one at the front, between your tongue's highest point and your lips. The size of each of those chambers determines which harmonics are loudest. Larger chambers make for lower resonances, and smaller ones make for higher resonances.

In "wah wah," your tongue is going up and down, which changes the amount of space between the top of the tongue and the larynx. The resonating harmonics are shifting from lower (when the space at the back is longer, at the "w") to higher (when the space at the back is shorter because the tongue is lower, at the "ah"). For instance, listen to just the harmonic around 750 Hertz from that "wah wah yeah yeah":

Yes, that's right, that high sound is part of the sound you heard in the original.

When we add together the different harmonics that resonate in the back of the mouth, together they sound like this:

Add them to the base note and together it all sounds like this:

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is what a wah-wah pedal does: It controls the relative loudness of the harmonics within a certain range, making lower ones quieter while rendering higher ones louder and vice versa. The mute on a trumpet produces the same effect — which is what makes that incomprehensible "teacher talking" sound on the Charlie Brown cartoon specials.

But wait, there's more! The actual sound in the recording is "wah wah yeah yeah," but as you will have noticed, with just the first set of harmonic resonances all you get is "wah wah wah wah." This is because the first set of resonances is controlled just by the tongue moving up and down, which it does the same in "yeah" as in "wah." To get "wah wah yeah yeah" you need all the harmonics higher than the ones we've heard so far — when you lose the upper harmonics, you lose the difference between "wah" and "yeah." And those upper harmonics are mainly determined by the shape of the part of your mouth in front of your tongue.

The difference between "wah" and "yeah" is, of course, that in "wah" your tongue is back and your lips are rounded, while in "yeah" your tongue is forward and your lips are not rounded. Rounding your lips makes the lower resonances stronger; moving your tongue forward makes the higher ones stronger. Have a listen to the harmonic around 1500 Hertz:

So when you add together all those different harmonics, plus the base note (the fundamental frequency, to use the technical term), you get something that sounds not like a stack of different notes but just a normal human voice:

That's how you make — and recognize — speech sounds. The same principle applies for making a musical instrument sound like a voice. And that explains why it's harder to understand what people are saying if you have hearing loss in part of your range — from, say, listening to too much rock music.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.