Obama and the GOP: 2008 debate foretold all

The last of Barack Obama's 2008 debates with John McCain previewed the kind of president he has become. It also painted a vividly distinct portrait of the current GOP.

The third and final presidential debate between Barack Obama and John McCain took place one year ago last week—Oct. 15, 2008. It's worth recalling that encounter now for its remarkable revelations of things to come.

The debate was marked by heated charges from McCain and cool responses from Obama—what The New York Times the next day called his "unflappable demeanor."

Running out of time and depleted of character, McCain strained in the debate to disqualify his young rival with attacks on Obama's character. The highlight, or lowlight, of this exercise was the Republican nominee's decision to mimic his hapless running mate by tying Obama to "a washed-up old terrorist" named William Ayers. Four decades before, Ayers had been a member of the violent Weather Underground; now he was a professor living in Obama's Chicago neighborhood.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For Americans fearful of financial collapse, McCain's focus was stunningly out of touch. Obama deftly dissed Ayers, condemning the "despicable acts" of this "radical domestic group" while noting that he himself was just 8 years old at the time the acts were committed. For good measure, he added that his principal association with Ayers was serving with him on a nonprofit board funded by "one of Ronald Reagan's ... close friends."

Obama's nonchalance left McCain seething. As the GOP's fading hopeful pressed on, his scattershot assault turned to ACORN, an organization most Americans had never heard of—and still haven't. The Democratic nominee brushed his elder aside and rebuked him: The fact that this has become "so important" to you, Obama told McCain, "says more about your campaign than it does about me."

But Obama's response actually said a great deal about him. The pre-debate hype had been rife with speculation about whether McCain would take the gloves off; when McCain did, Obama side-stepped his jabs and held to his own chosen ground—the economy and health care. He refused to be distracted or dragged into the muck.

This was the same Obama who, in his first days in office, ignored the alternating alarms of the daily news cycle and soon signed into law the largest stimulus package in the history of any nation on earth. He held to his economic course in the face of those on the left who argued that he was doing too little and those on the right who trotted out old shibboleths about big government and big spending.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The day of the third debate marked one of the Dow's worst falls; exactly one year later, the Dow climbed above 10,000. Soon, Obama will be able to report that job losses have ended and job growth has resumed. Obama refused to be pushed off the path to a new prosperity; and if he has to adjust along the way, he'll display the same equanimity with which he disposed of McCain's modern-day McCarthyism.

The debate previewed not only Obama's skill and temperament, but the nature of the Republican opposition. It wasn't a long way from suggesting that Obama had associated with terrorists to smearing him as a "socialist" or "communist"—or as the "birthers" would put it, someone who is literally un-American. McCain himself actually took on a supporter for calling Obama "an Arab." But in echoing the darker impulses of the Republican base that night, he foreshadowed the dominant nature of today's GOP opposition—personal, bitter, and almost entirely negative.

McCain also used the debate to trot out Joe the Plumber, who was mentioned 24 times, more than any other subject. Joe pointed toward the rise of the stunt-ridden, misinformed and disinforming populism that twisted the national debate this past summer. Indeed, Joe set the table for the tea parties of August 2009.

Tea party petulance led some to complain that Obama had waited too long to act, or that he should have sent to the Congress legislation drafted in the White House and, Clinton-like, simply ordered its passage. This represented more instant analysis—or panic—to which the president refused to yield. Instead, he bided his time until he determined the moment was right to assume center stage—without elbowing aside senior legislators and jeopardizing the margin needed for victory.

McCain's reluctant deployment of the politics of personal destruction in the third debate reflected another reality, then and now: that Republicans resort to attacks because they lack answers.

When Bob Schieffer, the debate moderator, asked if the candidates would give up any of their proposals due to the economic crisis, McCain sounded befuddled and formulaic. He cited his "new" economic plan (though it was far from clear he'd had an "old" one) before lurching into ideological dogma: he favored an across-the-board federal spending cut. It was a no-brain non-starter, a position that even Dick Cheney had dismissed as "Hoover economics."

Yet throughout 2009, congressional Republicans embraced it, standing almost unanimously against the economic recovery plan and urging spending cuts that would have deepened and prolonged the downturn. When the latest budget report revealed that the deficit was $200 billion to $400 billion lower than previously forecast—in part because the feds had rescued the financial sector—the House GOP leader demanded that the government "stop spending taxpayers' money we don't have." It was an easy invocation of economic myth; if actually adopted, his policy would reverse the recovery and push unemployment toward levels last seen in the 1930s.

Similarly, the GOP health-care plan is ... Quick—can anyone describe it? Empty of ideas, full of grotesque fury about nonexistent "death panels," is it any wonder the GOP has a favorable rating of 24 percent in the latest Pew poll?

As health-care legislation churns toward completion—with Obama steady in the face of pressure and controversy—it becomes more evident each day that he will be the last president who has to fight for national health reform.

The final McCain-Obama debate now seems deep in the past. But it proved to be a reliable prologue and predictor. The attacks on Obama's character only showed the strength of his character. And the ugliness of those attacks, combined with the emptiness of the Republican "ideas" expressed by McCain, foretold the character of a political party that does little but seethe and sputter as history moves on.

-

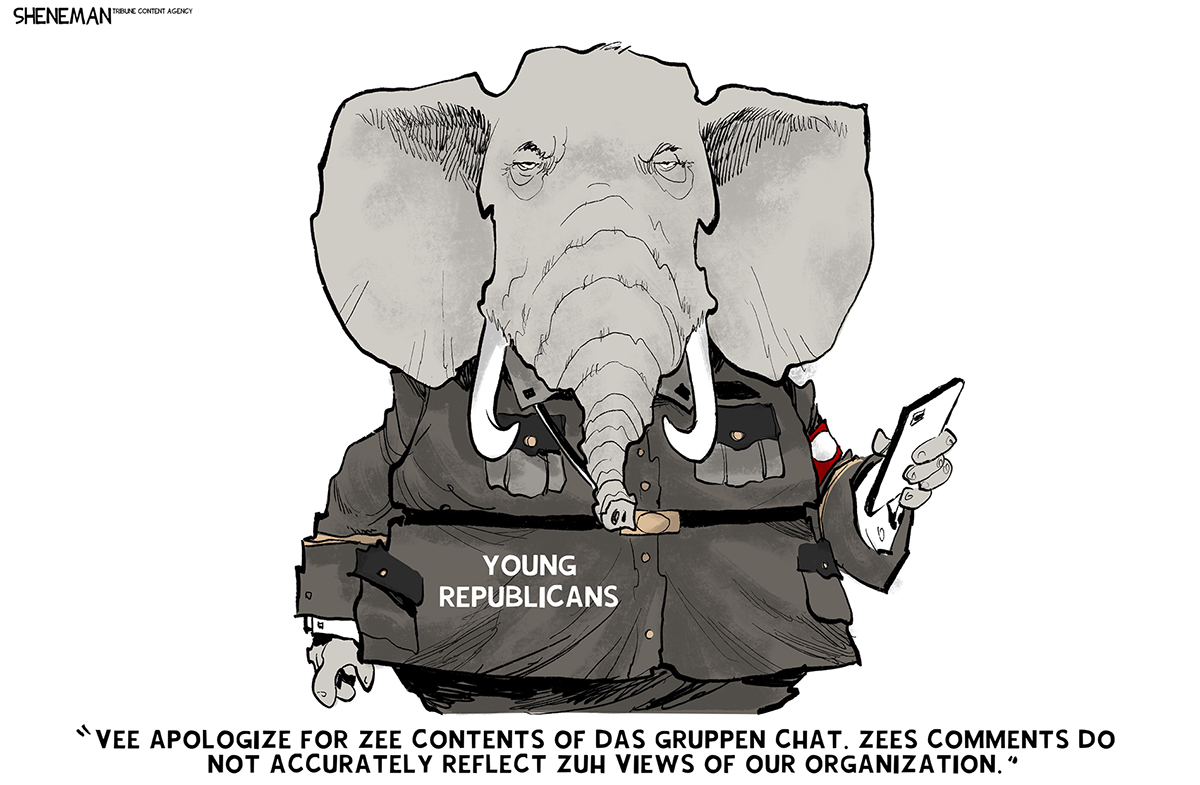

Political cartoons for October 26

Political cartoons for October 26Cartoons Sunday’s editorial cartoons include Young Republicans group chat, Louvre robbery, and more

-

Why Britain is struggling to stop the ransomware cyberattacks

Why Britain is struggling to stop the ransomware cyberattacksThe Explainer New business models have greatly lowered barriers to entry for criminal hackers

-

Greene’s rebellion: a Maga hardliner turns against Trump

Greene’s rebellion: a Maga hardliner turns against TrumpIn the Spotlight The Georgia congresswoman’s independent streak has ‘not gone unnoticed’ by the president

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'