Don't blame globalization, China, or outsourcing for the Baltimore riots

It's not their fault

Pro tip: If you're a civic leader, and riots are sweeping your city, close your social networking apps. Put your smartphone down. It is probably not the best time to take to Facebook or Twitter and start offering a mini-manifesto about the downsides of U.S. trade policy.

Case in point: John Angelos, chief operating officer of the Baltimore Orioles. On Monday night, as Baltimore was besieged by rioters, Angelos let loose a 323-word, 2020-character tweetstorm. After his team's game with the Chicago White Sox was canceled, Angelos decried the violence and looting, said due process must be respected, and then started channeling Elizabeth Warren:

That said, my greater source of personal concern, outrage and sympathy beyond this particular case is focused neither upon one night's property damage nor upon the acts, but is focused rather upon the past four-decade period during which an American political elite have shipped middle class and working class jobs away from Baltimore and cities and towns around the U.S. to third-world dictatorships like China and others, plunged tens of millions of good, hard-working Americans into economic devastation, and then followed that action around the nation by diminishing every American's civil rights protections in order to control an unfairly impoverished population living under an ever-declining standard of living and suffering at the butt end of an ever-more militarized and aggressive surveillance state. [John Angelos]

Angelos is a progressive Democrat, like his father, Peter, the Orioles' long-time majority owner who made his millions suing big business. And here, perhaps predictably, Angelos the younger is offering a too-simple story of economic injustice perpetrated by Corporate America and its lackeys in Washington. If not for unfair trade deals and the job offshoring they promote, he seems to suggest, America's immediate postwar era of good-paying, lifetime factory jobs would have never ended. This is a bit of economic nostalgia that even President Obama engages in from to time. As Obama said in a 2012 speech, "In the decades after World War II there was a general consensus that the market couldn't solve all of our problems on its own. …This consensus, this shared vision led to the strongest economic growth and the largest middle class that the world has ever known. It led to a shared prosperity."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That golden age could not last indefinitely, of course. Eventually the other advanced industrial economies recovered and began competing with American companies and workers. They were later joined by a rising Asia — first Japan and then South Korea, China, and India. American cities built around manufacturing — be it cars in Detroit or steel in Baltimore and Pittsburgh — suffered greatly. And as global competition increased, machines got better, allowing companies to generate more output with fewer workers. Manufacturing output as a share of GDP has actually been pretty stable since 1960, even as manufacturing employment has fallen by more than half.

The correct reaction to these macroeconomic forces — ones common to all post-industrial economies — was not to construct walls and smash machines but to try and adapt to this new environment. One way was to boost job market incomes through the tax code and government. America did just that, with some success. From 1979 through 2011, according to the Congressional Budget Office, inflation-adjusted household income for the broad middle class rose by 40 percent after taxes and government transfers. Income growth was even stronger in the bottom 20 percent, rising by 48 percent. Likewise, the share of Americans living in poverty has fallen by three-quarters since the mid-1960s thanks to an expanded safety net. American living standards certainly have not declined over the past four decades.

Nor have things gotten worse in those developing nations to which Angelos referred. In fact, they've gotten a whole lot better thanks to trade. In that "third world dictatorship" of China, global trade and investment have pulled some 700 million people out of extreme poverty. That reality, perhaps the biggest economic story since the Industrial Revolution, is a pretty big win for globalization.

But not everybody wins. These economic changes continue to buffet the American middle, especially at the lower end. For decades, the middle class shrunk because families were moving up the income ladder. Now it's because they're falling down it. Things are particularly tough for low-skill men — and maybe this is what Angelos was really getting at — whose wages are stagnant at best since the 1970s and whose labor force participation has declined sharply. Overall, the share of American men 25- to 54-years-old who are not working has more than tripled since the late 1960s. And of that group, according to one survey, 85 percent do not have a college degree, while a third have a criminal record.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So rather than railing at trade, maybe push for labor market reforms, such as expanding wage subsides, non-college pathways to the middle class, and making it easier for workers to avoid disclosing criminal records during the hiring process. Like a lot of other cities and rural areas in America, Baltimore needs more education and opportunity — not less trade with China.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

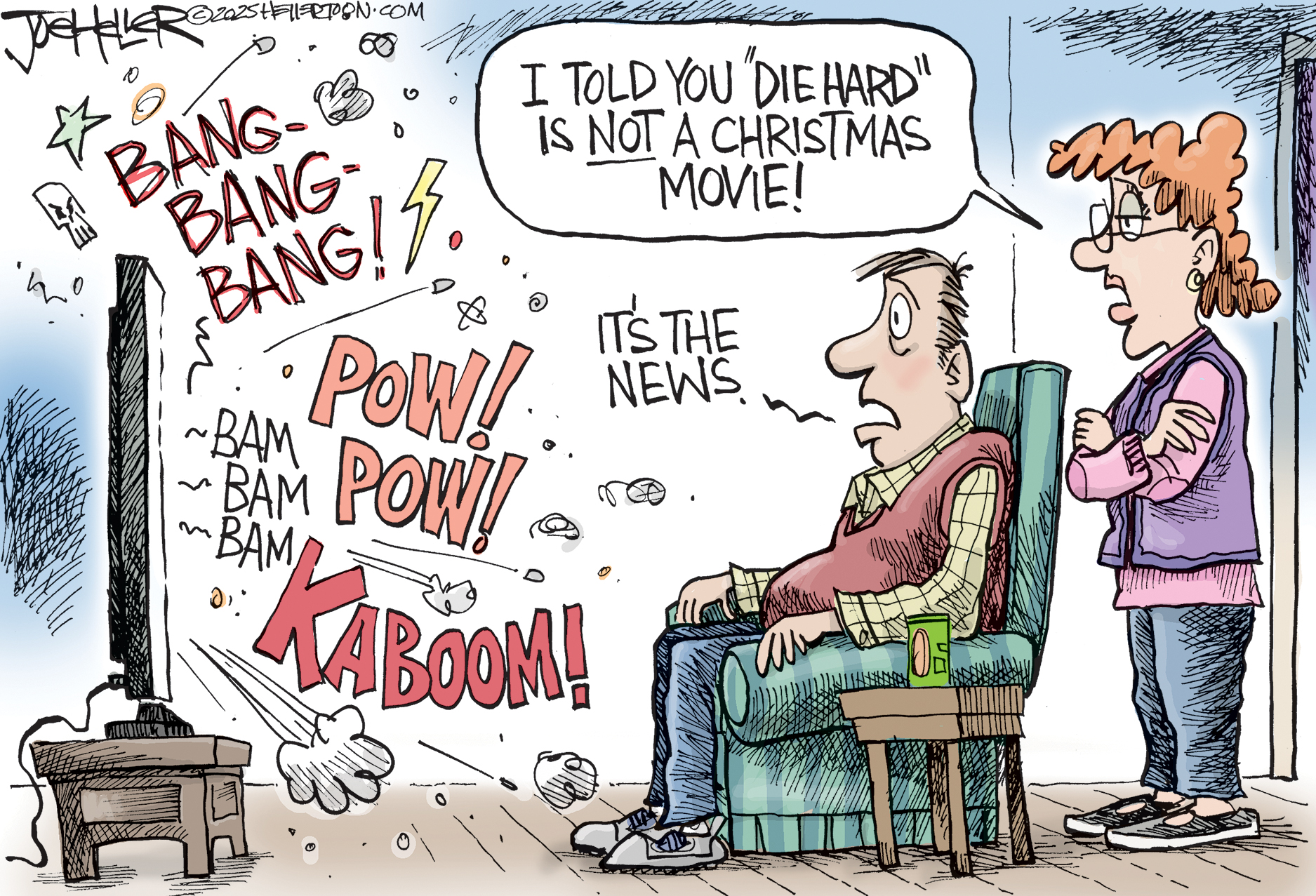

Political cartoons for December 21

Political cartoons for December 21Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Christmas movies, AI sermons, and more

-

A luxury walking tour in Western Australia

A luxury walking tour in Western AustraliaThe Week Recommends Walk through an ‘ancient forest’ and listen to the ‘gentle hushing’ of the upper canopy

-

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers want

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers wantThe Explainer White supremacism has a new face in the US: a clean-cut 27-year-old with a vast social media following

-

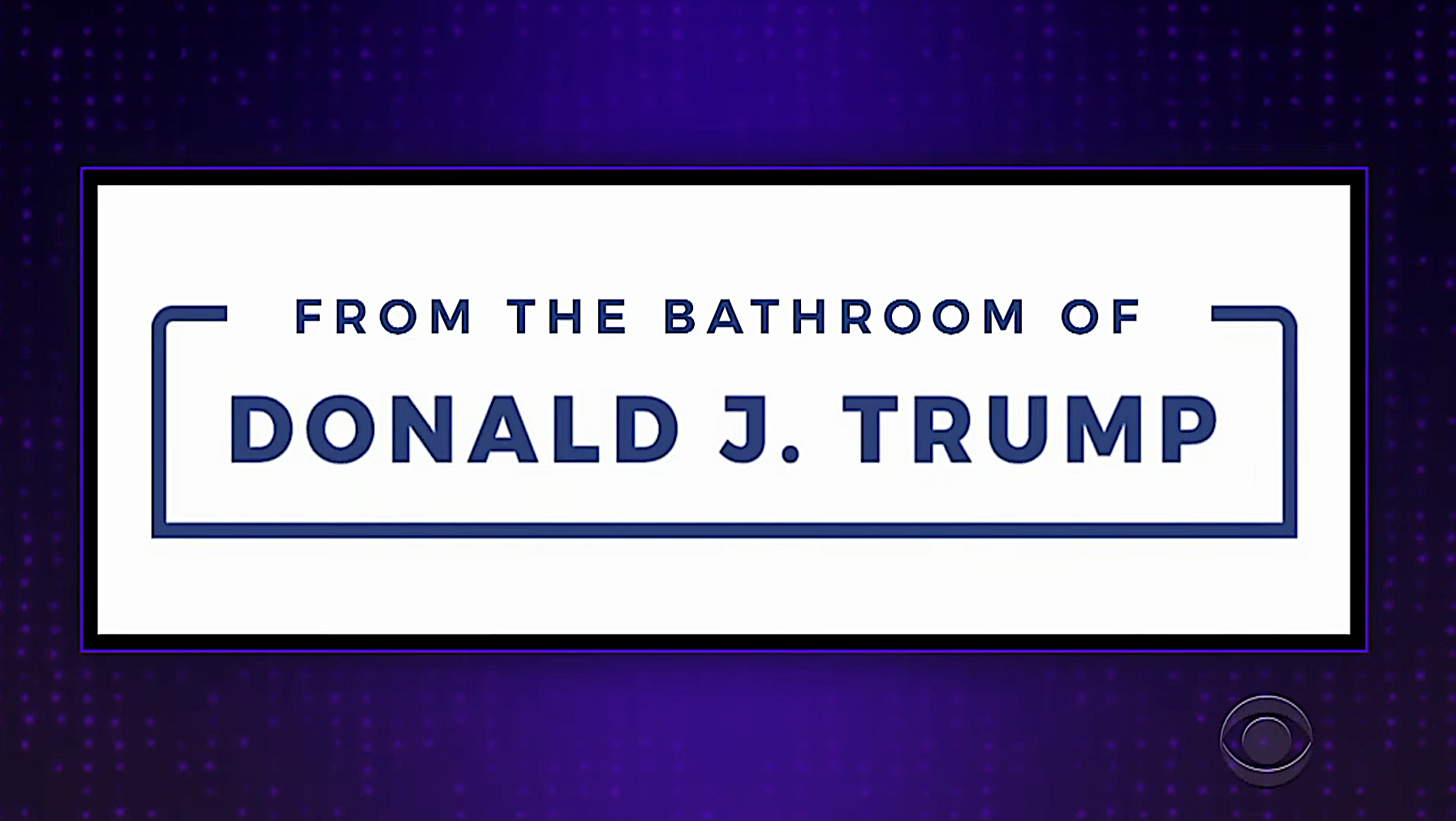

Late night hosts joke about Trump's forced exodus from Facebook to blog

Late night hosts joke about Trump's forced exodus from Facebook to blogSpeed Read

-

Fox News admits Biden doesn't actually want to cancel meat. Late night hosts pounce anyway.

Fox News admits Biden doesn't actually want to cancel meat. Late night hosts pounce anyway.Speed Read

-

Manhattan D.A. will stop prosecuting sex workers, not their clients, pimps, or sex traffickers

Manhattan D.A. will stop prosecuting sex workers, not their clients, pimps, or sex traffickersSpeed Read

-

John Oliver explains personal bankruptcy, how credit card lobbyists and lawyers make it much worse

John Oliver explains personal bankruptcy, how credit card lobbyists and lawyers make it much worseSpeed Read

-

John Oliver explores problems with U.S. nursing homes and long-term care, suggests you pay attention

John Oliver explores problems with U.S. nursing homes and long-term care, suggests you pay attentionSpeed Read

-

John Oliver tries to explain whether you should worry about the enormous U.S. national debt

John Oliver tries to explain whether you should worry about the enormous U.S. national debtSpeed Read

-

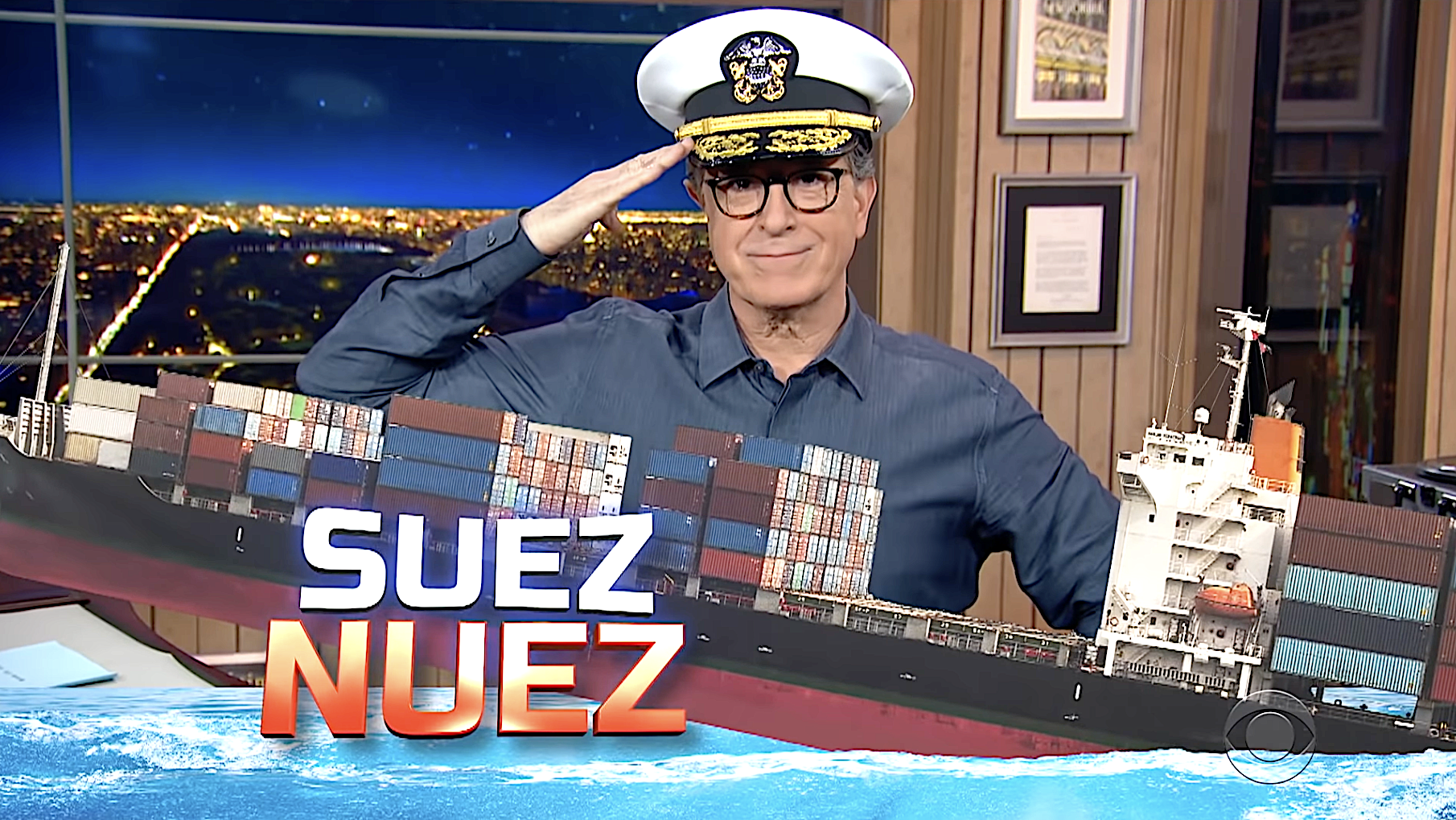

Late night hosts laugh at the giant ship blocking the Suez Canal, chide Fox News for fake Kamala Harris scandal

Late night hosts laugh at the giant ship blocking the Suez Canal, chide Fox News for fake Kamala Harris scandalSpeed Read

-

Utah governor signs bill requiring porn blocking on all new smartphones and tablets

Utah governor signs bill requiring porn blocking on all new smartphones and tabletsSpeed Read