Ben Carson, and the failure of black conservatives

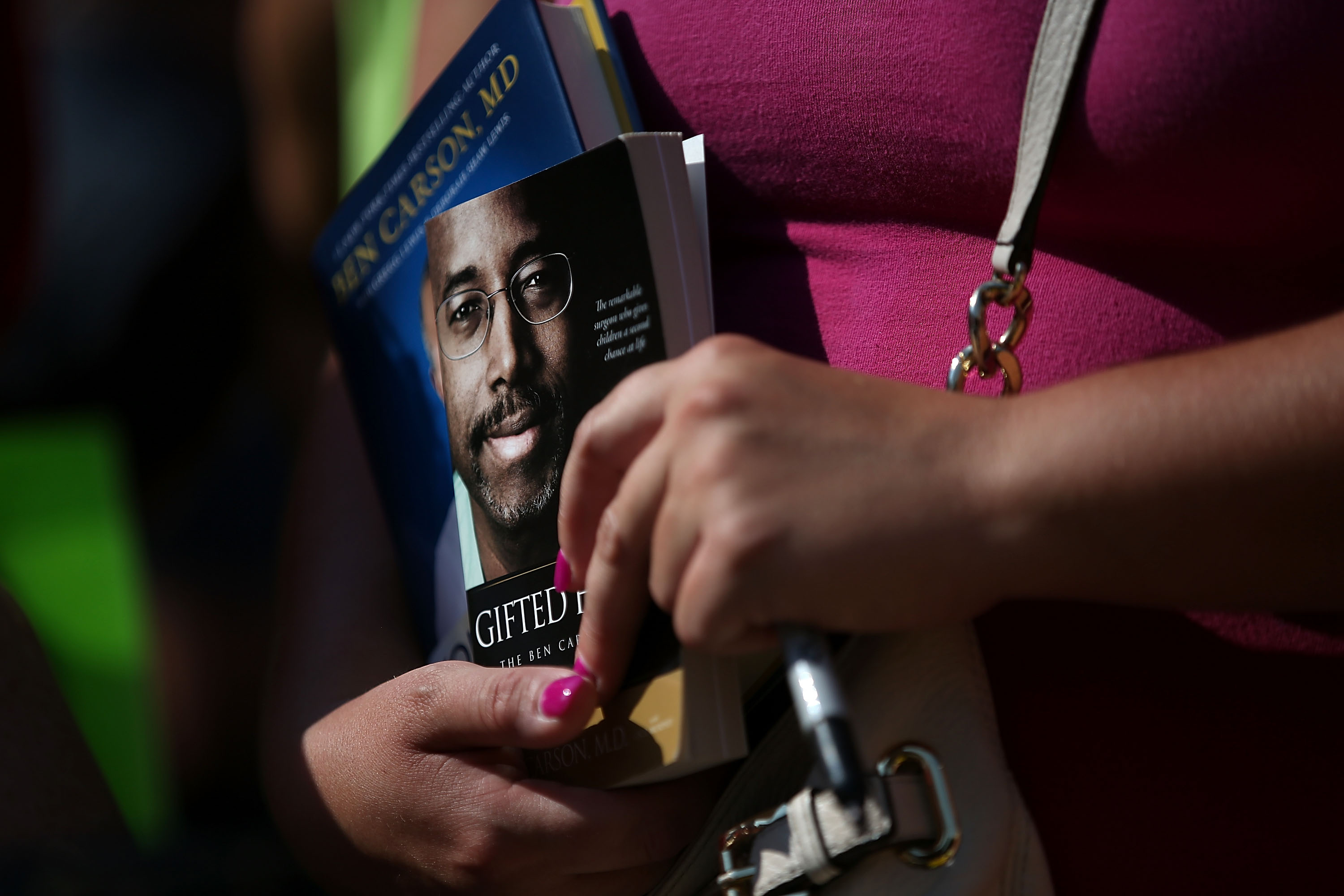

I was 17 when I first read Ben Carson's biography Gifted Hands. I can't believe the presidential candidate is the same man.

I was a 17-year-old teenager growing up on the west side of Detroit when I first read Ben Carson's biography Gifted Hands.

The first thing that caught my attention were the similarities in our childhoods: He grew up poor; so did I. Carson's mother couldn't read; my grandmother, who was my legal guardian until she died soon after I finished high school, could only read and write her name. Young Carson got in trouble as a teen and nearly stabbed a friend; when I was 12 years old, I had an almost fatal run-in with my uncle while he was high on drugs. Carson earned his bachelor's from Yale University and finished medical school at the University of Michigan. Though I would eventually receive both my undergrad and graduate degrees elsewhere, I, like many kids from Detroit, often dreamed of being a Wolverine.

And though I had no idea what I wanted to be in life, I knew I wanted to do something great. Maybe I wouldn't become a neurosurgeon famous for separating conjoined twins, but perhaps I could become something equally spectacular.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I knew nothing of Carson's politics back then. I was 17 and didn't care. He was a black man from the hood who "made it." His was an inspiring story, full of adversity overcome, of hard-work and perseverance. That's all that mattered to me. What I didn't realize as a teenager, however, was what that same story would one day mean to white, conservative America.

Ben Carson is now not only running for president as a Republican, but he's arguably leading the GOP field. And in an era where the biggest cheers of the Republican debates go to takedowns of "political correctness" and the media, Ben Carson is taking advantage, warping his personal story into misbegotten political and racial analysis.

In August, when a Fox News moderator asked Carson during a GOP debate how he would address strained race relations in America, he said that the "purveyors of hatred take every single incident between two different races and try to make a race war out of it and drive wedges into people." He said nothing about the structural issues causing the racial divide between black and white Americans; he just blamed the media.

In September during his tour of Ferguson, Missouri, where 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot and killed by former police officer Darren Wilson, Carson said, "We need to de-emphasize race and emphasize respect for each other." He added that he was raised to respect police and "never had any problem."

This is Carson's M.O.

When Carson speaks to the mostly white audiences who support him, he positions himself as a black person who doesn't "complain" about racism. He argues that we need to move beyond having difficult discussions about race.

And his messaging during his campaign has been crystal clear: I am who I am because I worked hard, and that is the best way to overcome racism. If you are black and cannot succeed like me, he tells his mostly white audiences, then only you are to blame for your problems — not police brutality, an unfair criminal justice system, or racist hiring practices.

It's a classic case of black conservatism, the belief that individual resolve should be enough to fend off structural racism. But Carson's auto-biography pokes holes in his own story. When you read about his life, you see someone who was not only exceptionally hard-working, but like all successful people, at times exceptionally lucky.

Had Carson actually succeeded in stabbing the friend he claims to have attacked as a teenager, Carson likely would have served time in jail and struggled to find work as a convicted felon; his right to vote probably would have been revoked, too. Carson likes to discuss how his short temper led to him go after people with rocks, bricks, baseball bats, and hammers. Hundreds of thousands of black people who made similar mistakes are caught in the racially predatory cycle of the criminal justice system that refuses to grant them second chances. Yet, he abhors the Black Lives Matter movement for daring to challenge the racist policies that could have very well prevented him from rehabilitating had he been been jailed for his wayward behavior.

Here's another telling anecdote: In his 1999 book The Big Picture, Carson wrote about an incident involving his mother being arrested in a suburb of Detroit because she, according to the arresting officer, fit the description of a woman who abducted an elderly couple; the charges were later dismissed with the help of a prominent lawyer friend who was also a fellow Yale alum.

Only a black person who reached the highest summit of social and professional achievement could have called his Ivy League buddy to get his mother out; the residents of Ferguson who were daily targets of rampant racial profiling, according to a Department of Justice report, did not enjoy such social pull.

But Carson, the presidential candidate, doesn't tell his white supporters about the pitfalls he narrowly avoided; he only talks about the heroic leaps he took in avoiding them. When I read Gifted Hands nearly 18 years ago as a young teenager, I never envisioned Carson becoming a 21st century Nat Turner — but neither could I foresee him dismissing racial injustice entirely. The culmination of Carson's success, as I now know, was not designed to accommodate any sense of responsibility for those in the black community who didn't "make it."

Instead, it is only tailored to assure white voters that they don't have to bear any of the racial baggage that comes with being black in America.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Terrell Jermaine Starr is a New York City-based journalist who covers U.S. and Russian politics. His twitter handle is @Russian_Starr.

-

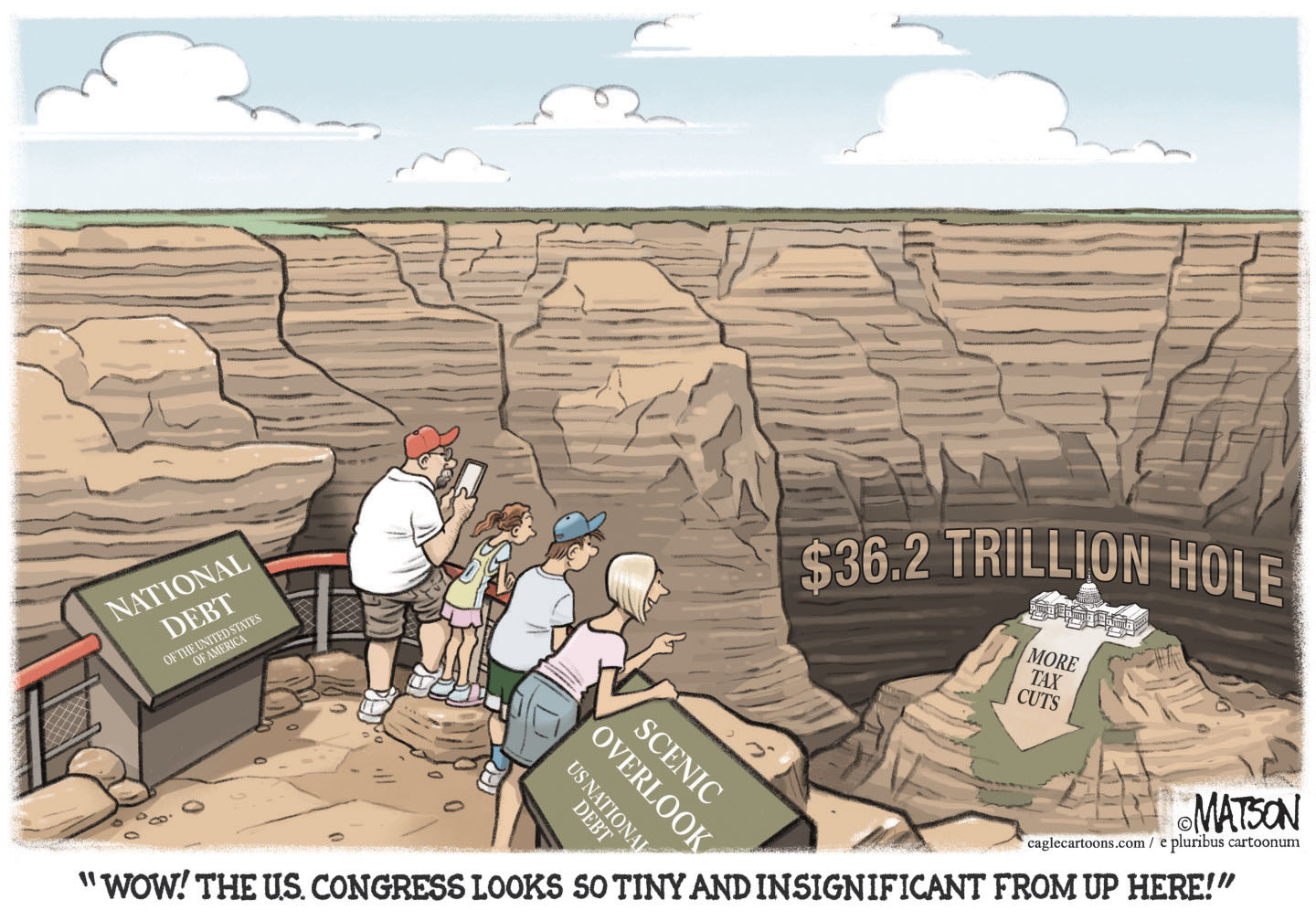

May 31 editorial cartoons

May 31 editorial cartoonsCartoons Saturday's political cartoons include how much to pay for a pardon, medical advice from a brain worm, and a simple solution to the national debt.

-

5 costly cartoons about the national debt

5 costly cartoons about the national debtCartoons Political cartoonists take on the USA's financial hole, rare bipartisan agreement, and Donald Trump and Mike Johnson.

-

Green goddess salad recipe

Green goddess salad recipeThe Week Recommends Avocado can be the creamy star of the show in this fresh, sharp salad

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

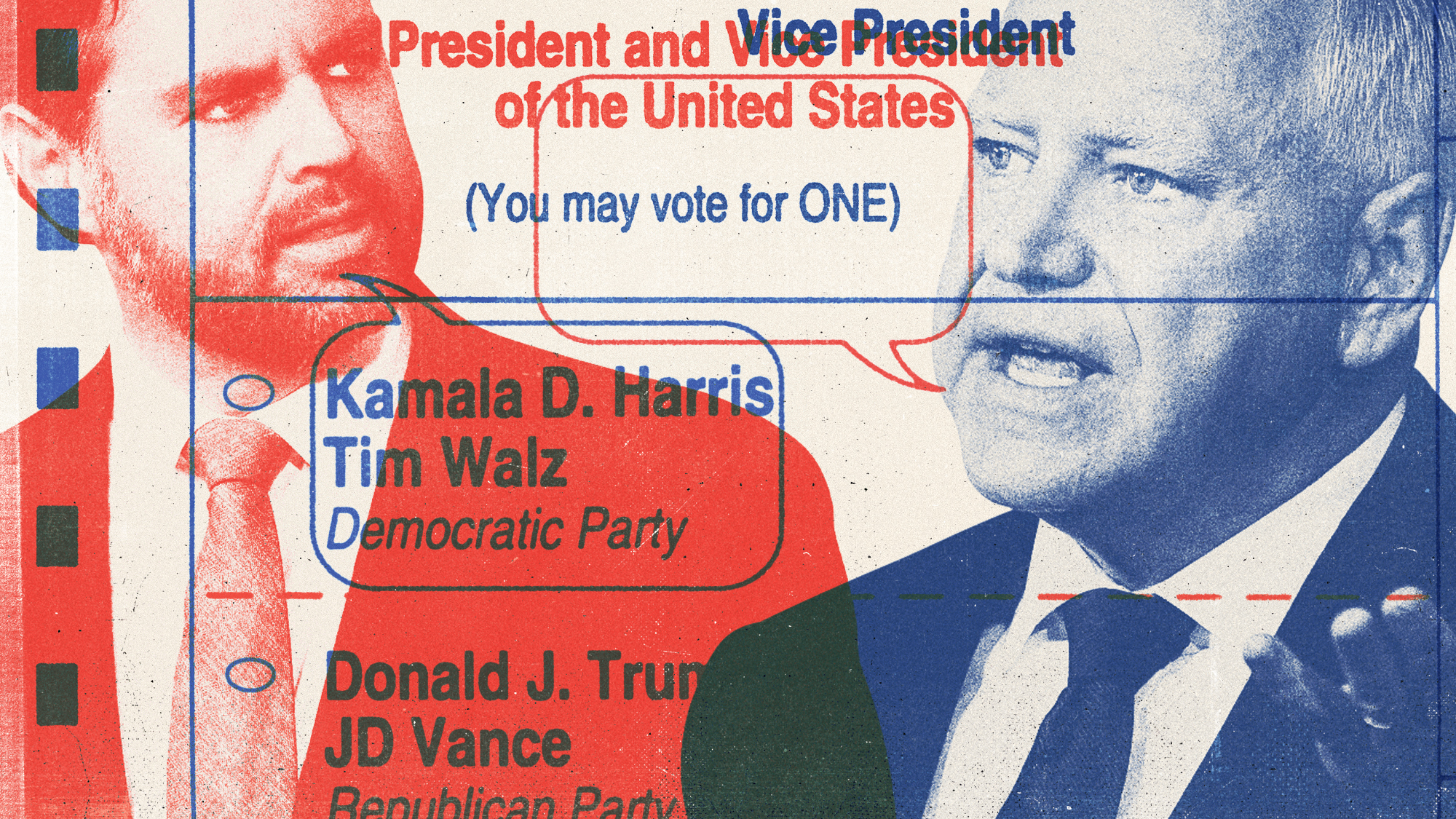

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy