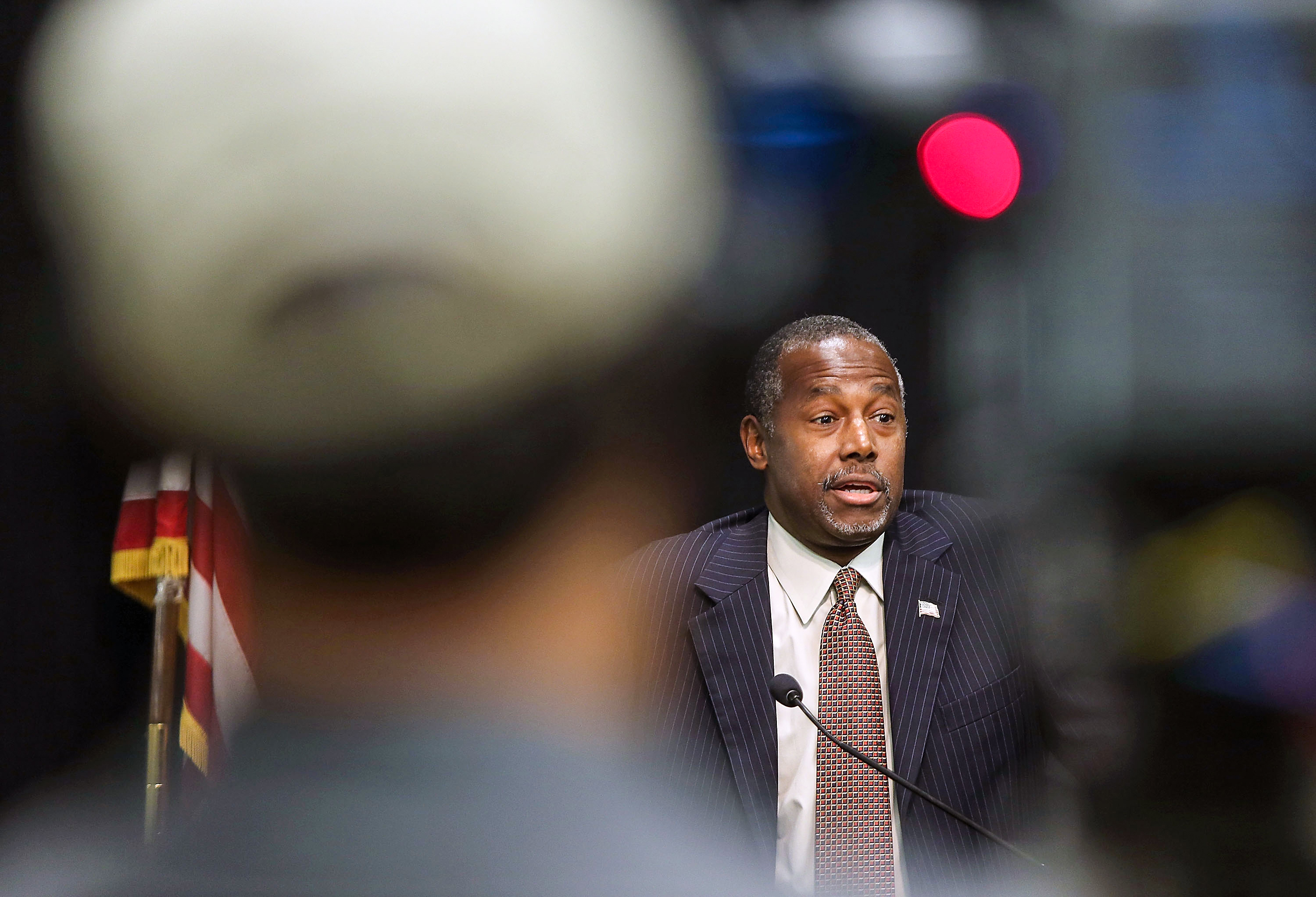

Ben Carson's economic confusion

The GOP frontrunner is a brilliant doctor. But on the economy, he's got an awful lot to learn.

Ben Carson, the GOP's putative presidential frontrunner, has got the economy all wrong.

It's not just that the rightly heralded neurosurgeon's tax proposal — a 10 to 15 percent flat tax on everything from wage income to corporate profits and capital gains — shows all the signs of having been made up on the fly. It's that the basic model he seems to have in his head for how jobs are created, and for how economic activity happens, is fundamentally broken.

Consider a few quotes Carson gave to Jim Tankersley at The Washington Post: "By the time I was a young attending neurosurgeon, I was really struck by the number of indigent people I saw coming in who were on public assistance, and who were not working," Carson said. "They were able-bodied people, and they were not working. I thought, this is out of whack." This comes amidst a longer lament by Carson about how government aid encourages dependency, and how America has failed to create an "environment that encourages entrepreneurial risk-taking."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There's a pretty simple assumption sitting beneath these observations: Namely, that jobs are available for people, if they were only willing to take the initiative. This idea — that jobs are just magically "there" — is incredibly common in American politics. (Here's a New York Times columnist recently indulging in it.) But this idea is also dead wrong. There is, in fact, a set supply of jobs out there. The macroeconomic policies we collectively choose as a society can certainly increase the set number of jobs, if we choose correctly. But if we choose poorly, there won't be enough jobs for everyone who needs one, no matter how hard we may "encourage" work.

It's true that some people on various forms of government aid are frequently not in the labor force because they've stopped actively searching for jobs. But even for people who are actively looking, there are still 1.5 job seekers for every job. That's the lowest that ratio has been since the Great Recession, and the last time the ratio was one-to-one was at the end of the boom of the late 1990s. A one-to-one ratio means full employment, which was somewhat common in the mid-20th century. But by the late 1970s — when Carson would've been a young attending neurosurgeon — full employment had vanished. And, other than that brief blip in the 1990s, it has not returned.

Moreover, thanks to a long history of deliberate oppression and social exclusion, the poor African Americans Carson grew up around during his long slog out of childhood poverty in Detroit — a story that is is genuinely remarkable and inspiring — have had an incredibly difficult time accessing the parts of the economy that are actually doing well. Their unemployment rate regularly outdistances the country as a whole, and by a wide margin.

All of which is to say: It's pretty iffy for Carson to imply that the people he saw in the hospital could have found work if they had merely tried. But he does at least acknowledge that we need to worry about job creation. That said, his recommended policies — "tax holidays for multinational companies, reducing government regulation of business, and cutting corporate tax rates," reports Tankersley — are once again based on a deep confusion.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The same history of racism that creates higher unemployment rates for African Americans has also forced many of them to live in extremely impoverished neighborhoods. Jobs are created by a feedback loop between people with money to buy goods and services and the business that make the investments and create the jobs to supply those goods and services. If an entire community is poor, if they have little to no money with which to buy things, no business is going to be able to create more jobs.

Carson's solutions assume the demand side of the loop — the ability of people to buy stuff — is fine, and it's the supply side of the loop that's being held back by government interference like taxes and regulation. But if that assumption is wrong, then all supply-side policy solutions will do is pile money up amongst the already wealthy without creating any jobs. Which is exactly what's happening in America. Corporate profits are soaring as a share of the economy. In one telling example, when Kansas cut its business taxes, no new jobs were formed. We've been playing with capital gains tax rates for decades with no appreciable effect on growth rates.

You can certainly argue that demand-side policy stimulus is good for fixing short-term economic collapses, and supply-side policy is for improving growth over the long term. But, to paraphrase economist Brad DeLong, the short term appears to be lasting an incredibly long time. The economy has been lacerated with one short-term wound after another for decades now.

This also leads into what's wrong with Carson's claim that the Federal Reserve is harming poor and middle-class savers by keeping interest rates down. If a community has scant income, then people are going to have a very hard time having any money left over to save. In fact, things are bad enough out there that half of American households have one month or less of savings on hand. Moreover, once an economic boom does arise, interest rates will naturally rise with it, as demand for capital and investment spreads and proliferates. But hiking interest rates first is a surefire way to strangle any potential boom in its cradle.

In his particular field, Ben Carson is a brilliant man. But it's a quirk of the modern world that there's simply so much to know that an individual who's brilliant in one area can be deeply ignorant in another.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

‘Let 2026 be a year of reckoning’

‘Let 2026 be a year of reckoning’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why is Iran facing its biggest protests in years?

Why is Iran facing its biggest protests in years?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Iranians are taking to the streets as a growing movement of civic unrest threatens a fragile stability

-

How prediction markets have spread to politics

How prediction markets have spread to politicsThe explainer Everything’s a gamble

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook