What Socrates could teach us about the Republicans' angry debate

Let's talk about Trump, Cruz, and the Greek notion of thymos

Last night's debate confirmed it: This is the Republicans' Year of Anger, for good and for ill.

It was obvious the moment Donald Trump — the master of the night's tone and tempo, not to mention the campaign's — clearly and calmly intoned that he freely accepted the angry branding foisted upon him by his foes. "I will gladly accept the mantle of anger," he announced.

But in this, he was not alone. It was an angry night for every relevant candidate onstage (and then some). Ted Cruz, more than coming into his own, delivered a cooler but in some ways even more brutal performance than Trump, using his lawyer's taste for blood in the water to push attacks on Trump and others as far as possible — sometimes (as with his dissection of "New York values") too far.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Chris Christie, the candidate most in favor of calculated crackdowns, happily played off his deep frustration with the often ungoverned quality of his opponents and their exchanges. "When you're a senator what you get to do is just talk and talk and talk," he fumed, "and you talk so much that nobody can ever keep up with what you're saying is accurate or not." As a governor — one of the last standing — it was a convergence of style, substance, and savvy.

And Marco Rubio, ostensibly the down-to-earth good humor boy, slipped all too easily into a darker key — one that had modulated, after a long evening of extremely heavy breathing over the way Barack Obama had created a grim "turning point in our history," into a new and disconcerting theme. Rubio breathed brimstone when he accused Cruz of relying on "political calculation" rather than "consistent conservatism," a hell of a charge coming from a candidate whose furious act of wriggling loose from his immigration record aced out Jeb Bush and transformed the field.

Every race this closely and bitterly contested is bound to become a lightning rod for human passions. But uniquely, in this one, the leading candidates are fighting over whose personal anger not only best reflects the political situation but represents the body politic. "It's not fear and terror, it's reality," Trump said — a line equally but differently resonant in the mouth of Christie, the law and order candidate, Rubio, for whom nothing matters if we aren't safe, or Cruz, who, more than any other, has taken a cue from Daniel Plainview and slant drilled with a vengeance into Trump's reservoir of populist fury.

Consistently hot-blooded as this moment may be, however, it is far too easy — for the media, especially — to get caught in the most self-conscious kind of performative outrage over all the outrage. We seem to have lost touch with a conceptual framework that can help us make sense of political anger today, which appears, as Ben Carson last night very nearly alleged, to come straight out of Satan himself.

To soothe this savage problem, however, we might reach back beyond the Judeo-Christian worldview to the ancient Greeks, who developed anger culture to towering heights not replicated since. Of course, it's possible to glimpse the real historical turning point when the anger culture that abounded in Athens was defeated by the forbearance culture of Jerusalem. "But now ye also put off all these; anger, wrath, malice, blasphemy, filthy communication out of your mouth," Christians are counseled (Col. 3:8); those who "obey unrighteousness, indignation, and wrath" are brought "tribulation and anguish" (Rom. 2:8-9).

Rendered in Greek, in these and other lines of scripture, two words are used together: thymos, the quick and spirited kind of anger, and orge, the deliberate kind that stews and waits.

From us, the nature of these differences demand some stewing and deliberation of their own. We are accustomed to thinking of pent-up, cultivated anger as especially dangerous in civic and psychological life. It's resentment. It's the righteous indignation that's so susceptible to demagoguery.

From the standpoint of Socrates, however, thymos is much more than this ironically depersonalizing fury. It is something akin to pride — but, again, not in our cheap sense of performative political emotion. It's our natural instinct to take our own side, violently if need be, when we feel or find ourselves in peril. It's our last-ditch effort to preserve our personal, individual integrity.

One manly-man who wasn't onstage last night recently referenced a "courage that comes from being so frightened or alarmed that you just need to speak up. That can also be put down as crazy and unpredictable, but it's not." Tom Hardy speaks the truth, but because we fear it's too intermixed with resentment, it's a truth we're afraid to give its political due. But so far thymos is having its way with this campaign, in the GOP and well beyond. If we cannot take charge of our Year of Anger, it will take charge of us.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

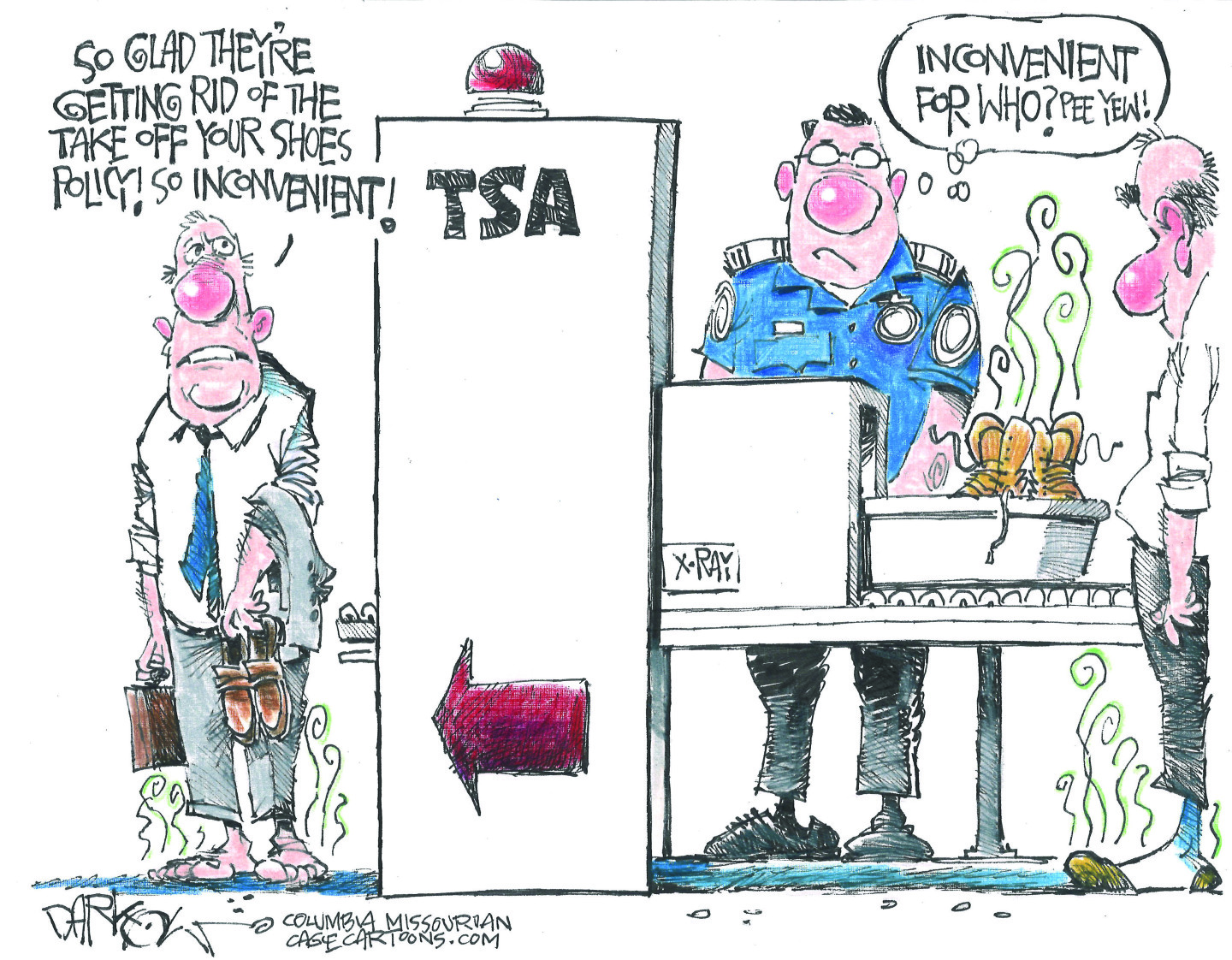

July 13 editorial cartoons

July 13 editorial cartoonsCartoons Sunday's political cartoons include new TSA rules, FEMA cuts, and Volodymyr Zelenskyy complimenting Donald Trump's new wardrobe

-

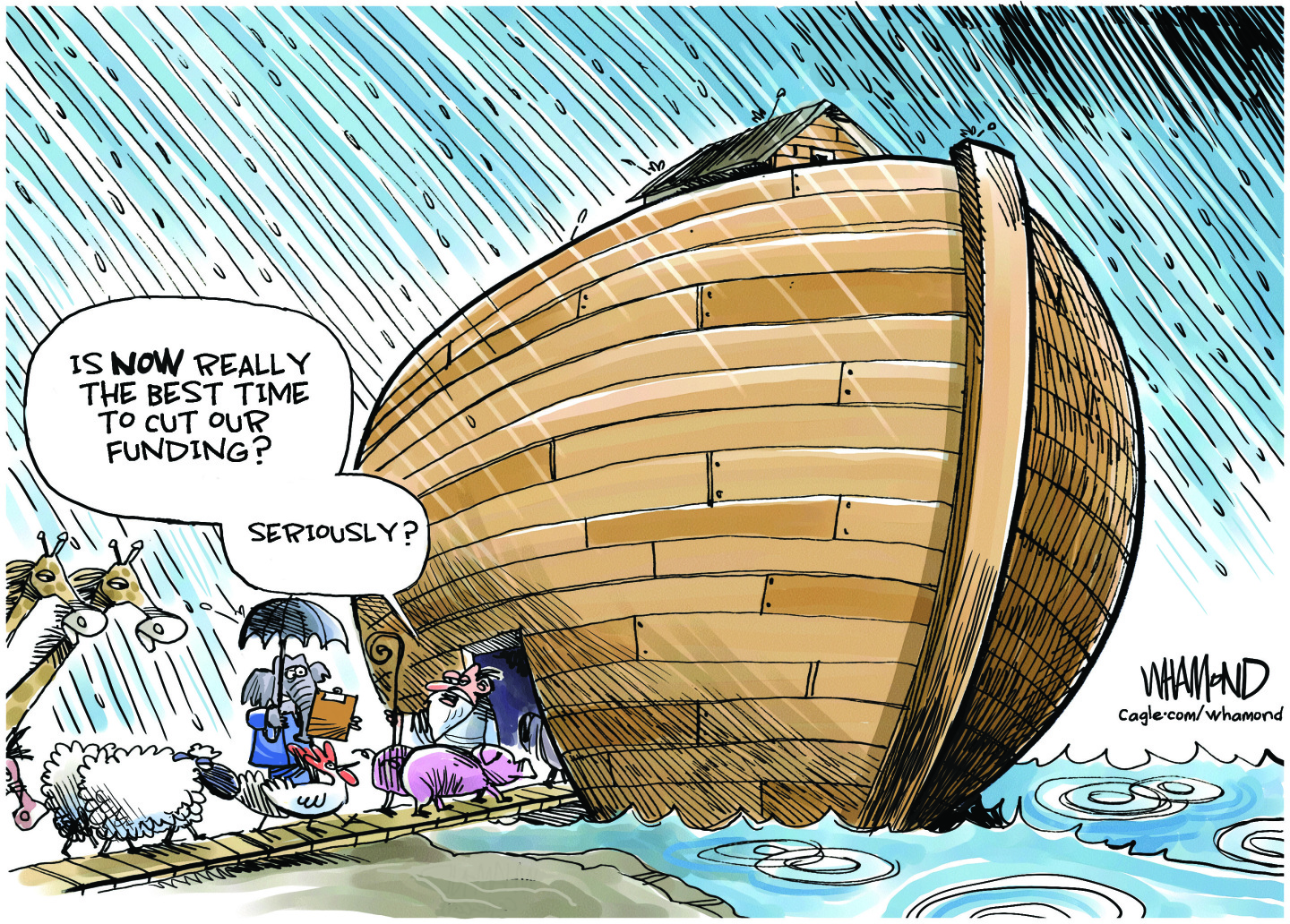

5 weather-beaten cartoons about the Texas floods

5 weather-beaten cartoons about the Texas floodsCartoons Artists take on funding cuts, politicizing tragedy, and more

-

What has the Dalai Lama achieved?

What has the Dalai Lama achieved?The Explainer Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader has just turned 90, and he has been clarifying his reincarnation plans

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?