Our age of political discontent

Why are so many Americans today fastening onto politics as the source and solution of their dissatisfactions?

Human beings are prone to perversion.

I don't mean sexual perversion, though that is sometimes a part of it. I'm talking about our broader tendency toward confusion about how to be happy. We seem to be oriented toward happiness (or flourishing), longing for it desperately, striving for it throughout our lives. Yet we also lack any clear sense of how to get there — which is why we seek it in so many different, sometimes contradictory ways: through love, work, family, faith, hobbies, entertainment, sex, travel, art, sports, and consumerism.

The gap between our desire for fulfillment and our failure to figure out how to achieve it leads to an equally wide variety of forms of human dissatisfaction.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ours is an age of rising discontent. We see it in surveys showing that large numbers of Americans think the country is in decline or on the wrong track. We see it in surging rates of suicide. We see it in the radical politicians who have captured the imaginations of so many during this presidential election cycle — with Donald Trump promising to make the country great again by way of a complete break from politics as usual, and Bernie Sanders advocating a political revolution to overthrow the rule and influence of the wealthy on the political system.

But we shouldn't take for granted the politicized forms of discontent that are so pervasive at the present moment. The fact is that there are many ways for people to understand and express their dissatisfaction. Why should ours be accepted uncritically?

If we look to history, we find several ways of understanding discontent — all of which survive in one form or another in our world.

One sees discontent rooted in individual psychology and advocates a therapeutic response. (The word psychology comes from the ancient Greek: reasoning [logos] about the soul [psyche].) For Socrates and Sigmund Freud, addressing unhappiness requires a turn inward, toward reflection on oneself — on one's deeply contradictory opinions about morality in the case of Socrates, and on one's subconscious hopes, wishes, longings, and fears in the case of Freud. For both, the key is fulfilling the edict to "know thyself," to determine what one truly wants, and what it would take to truly satisfy those true desires.

A second tradition, represented in different ways by ancient Greek tragedy, the Hebrew Bible, and Christian civilization, views discontent as an understandable response to the human condition. We are victims of fate, exiled, fallen, broken, lost, wandering through a vale of tears; no wonder we often feel confused about how to live and what would fulfill us. For the Greek tragedians, the only adequate response is resignation through the mediation of tragic drama. For the monotheistic traditions, we can find a modicum of contentment by turning our eyes to God — living according to his law (in the case of Judaism) or following Jesus (in the case of Christianity) — while we await the only thing that will relieve our suffering for good: the divine redemption that awaits us with the arrival or return of the Messiah.

In one of the most important books of intellectual history of the past quarter century, political theorist Bernard Yack told the story of how philosopher Immanuel Kant inadvertently gave birth to yet another form of discontent — one that treats some object within the world as the source of our dissatisfaction. For Kant himself, the object could never be removed or overcome: It was the world of material causality itself, within which we live out our lives. But part of us nonetheless rebels against it, striving for the complete self-determination that characterizes the free will when engaging in moral deeds. Human beings are somehow both radically subject to forces beyond our control and also radically free to determine our own actions.

This permanent tension or contradiction at the core of human life is something that Kant's philosophic successors — including Friedrich Schiller, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Nietzsche — refused to accept. Sensing the power of freedom and self-determination within themselves, or detecting it in the evolution of the human spirit through history, these thinkers expressed a "longing for total revolution" in which humanity would at long last overthrow the obstacle to its realization of complete fulfillment within the world.

For Marx, this obstacle was the socio-economic order of capitalism, which needed to be smashed to pieces in a total revolution in which the working class would (in Marx's words) "rid itself of all the muck of ages and fit itself to found society anew" in an act of radical self-determination. A faint echo of this longing can be detected in the enthusiasm of (mostly young) Democrats and independent voters for Bernie Sanders' presidential campaign and its calls for a "political revolution."

But the longing for total revolution also comes in right-wing forms that fasten onto "modernity" as the source of our discontent. In one mode, the longing to overthrow or radically transform modern life points in the direction of the fascistic desire for a mass movement and its Great Leader to break from the past and present through a monumental act of will. Traces of this impulse can be heard in some of Donald Trump's rhetoric about how he will single-handedly bring about a national renewal that will transform and revitalize the United States.

The anti-modern tendency also comes in a more quietistic mode that doesn't so much seek a total revolution as respond to the impossibility of such a revolution by advocating withdrawal into an insular community that is somehow in but not of the modern world. Blogger Rod Dreher's "Benedict Option" for the religious right (inspired by the work of Catholic philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre) takes this form, holding out hope that traditionalist Christians might manage to overcome their deep dissatisfaction with aspects of modern life by a severing of ties with secular trends they consider the source of their unhappiness.

With all of these varieties of discontent to choose from, why are so many Americans today fastening onto politics as the source and solution of their dissatisfactions?

The answer is no doubt very complicated. But I suspect a good part of it can be traced to the interaction of democracy with the communications technology that increasingly suffuses our lives.

Democracy in a nation of 318 million people requires the mediation of elected representatives. But one member of Congress represents over 700,000 citizens. This can work if people don't pay much attention and simply allow their representatives to do their jobs without constant oversight. But saturation news coverage keeps citizens more informed than ever before about day-to-day happenings (and petty corruption) in Washington, on Wall Street, and around the country, while social media gives everyone a megaphone to chime in, state an opinion, and argue it out in public.

As a result, each of us feels like we should be having a greater say, but the system is no more capable of responding to so many demands than it ever was or ever will be. And that produces a feeling of frustration and impotence, as growing numbers conclude (correctly) that the obstacle to us getting what we want is nothing less than the system itself. Which tempts us further toward radicalism.

Might enough people eventually come to long for total revolution that the system itself could face an "extinction-level" threat?

I wouldn't say it's likely. But any time large numbers of people come to identify the source of their discontent not with something in themselves or in the human condition itself but with a removable obstacle within the political world, it's possible.

Not yet. But maybe sometime soon….

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

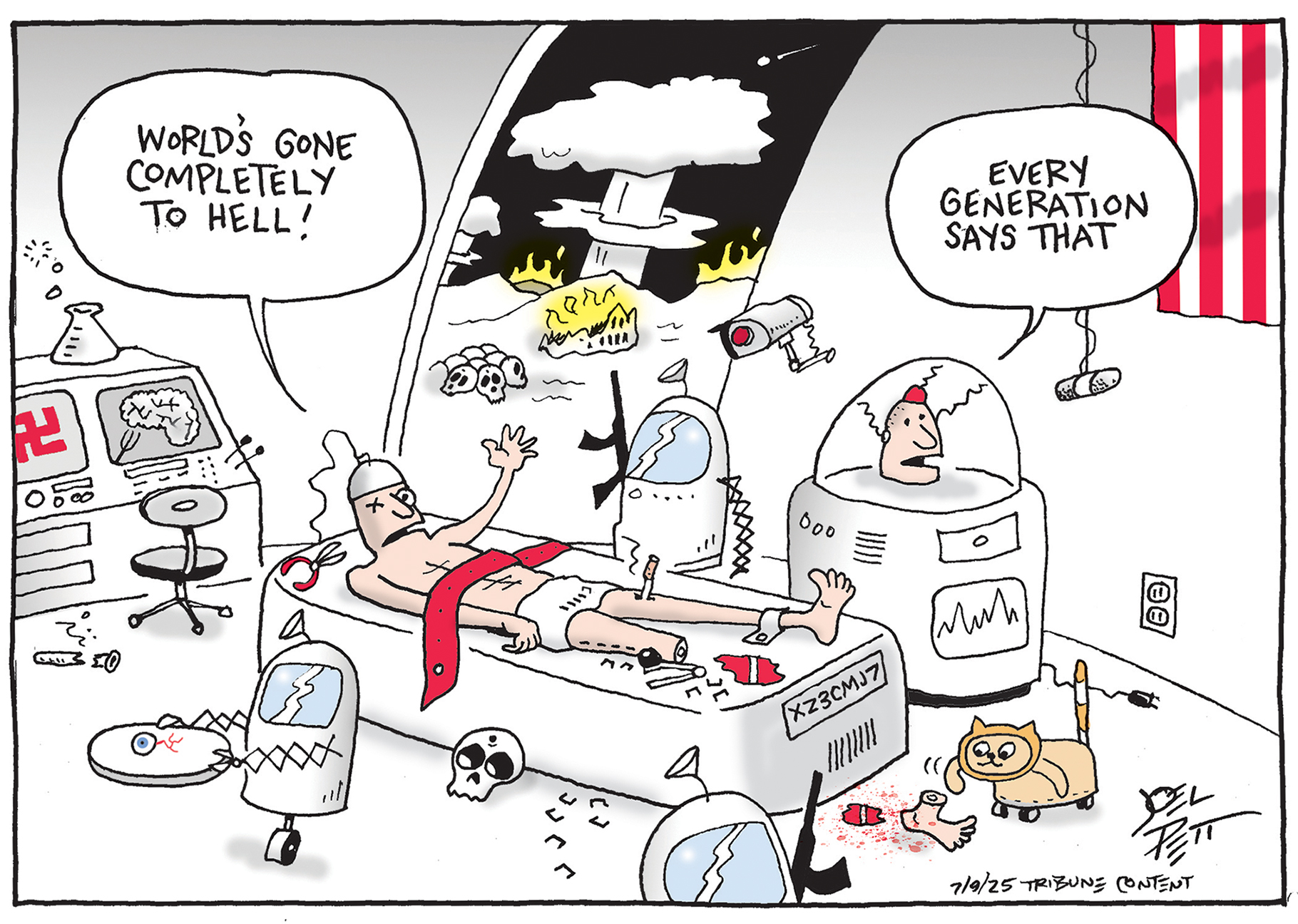

July 12 editorial cartoons

July 12 editorial cartoonsCartoons Saturday's political cartoons include generational ennui, tariffs on Canada, and a conspiracy rabbit hole

-

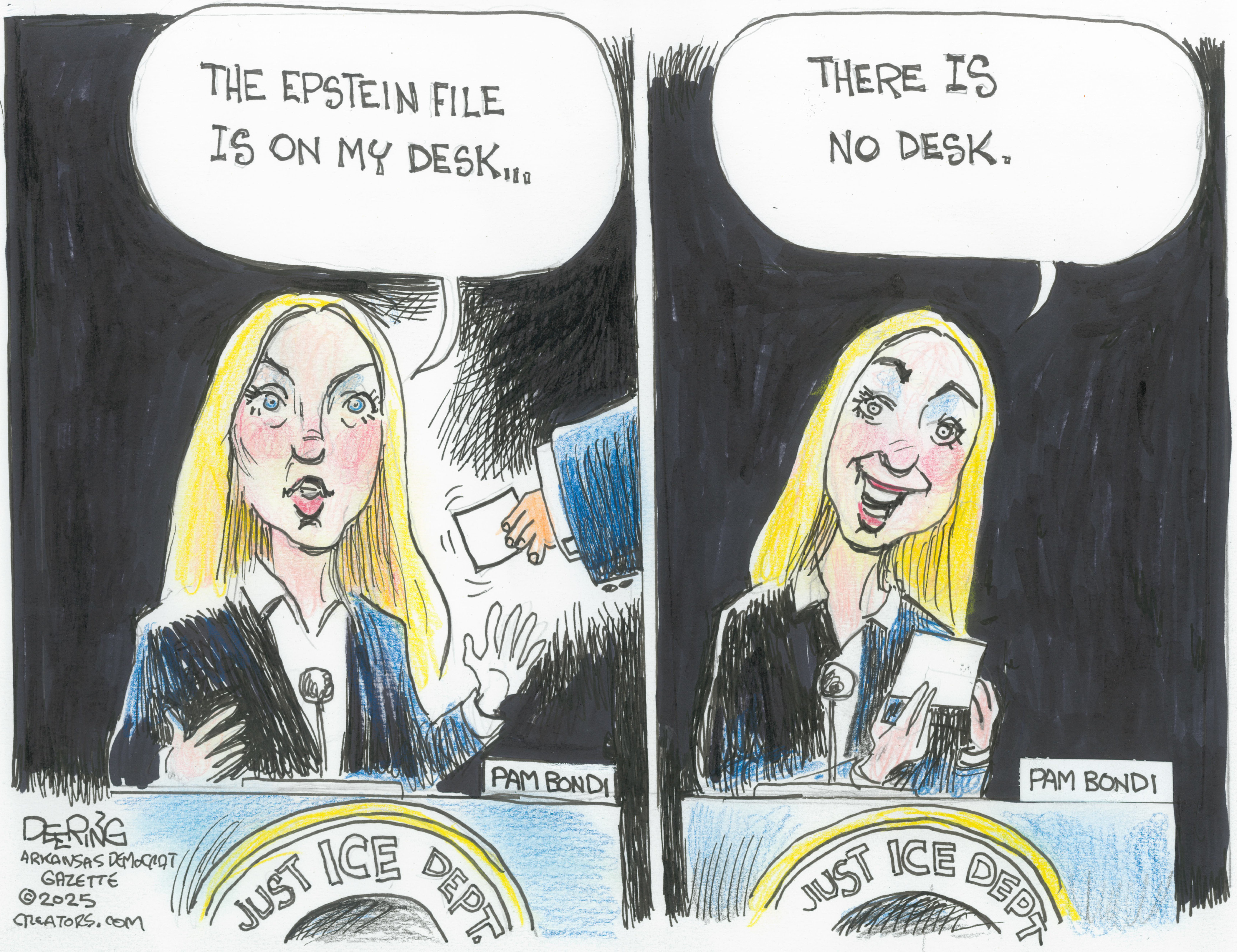

5 unusually elusive cartoons about the Epstein files

5 unusually elusive cartoons about the Epstein filesCartoons Artists take on Pam Bondi's vanishing desk, the Mar-a-Lago bathrooms, and more

-

Lemon and courgette carbonara recipe

Lemon and courgette carbonara recipeThe Week Recommends Zingy and fresh, this pasta is a summer treat

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?